Farmington High School grad earns prestigious award from American Bar Association

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the spring of 1967, John Echohawk — a 1963 Farmington High School graduate who had just earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of New Mexico — paid a visit to the UNM School of Law to make sure his application for admittance had been received and to check on scholarship information.

When he got there, he was surprised, and somewhat dismayed, to be told the dean of the school wished to speak with him.

“I thought, ‘I’m not even admitted to law school yet, and I’m already in trouble,’” Echohawk said.

As it turns out, Echohawk had nothing to worry about. The dean only hoped to alert him to the existence of a new scholarship program run by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity — part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society program — that was designed to encourage young Native American students to go to law school in preparation for practicing tribal law.

There was a woeful lack of Indigenous lawyers in the United States in those days, Echohawk said, explaining that, by one estimate, there were only 25 of them. An estimated 1,000 were needed simply to handle the amount of litigation in which Native tribes and individuals were involved, he said.

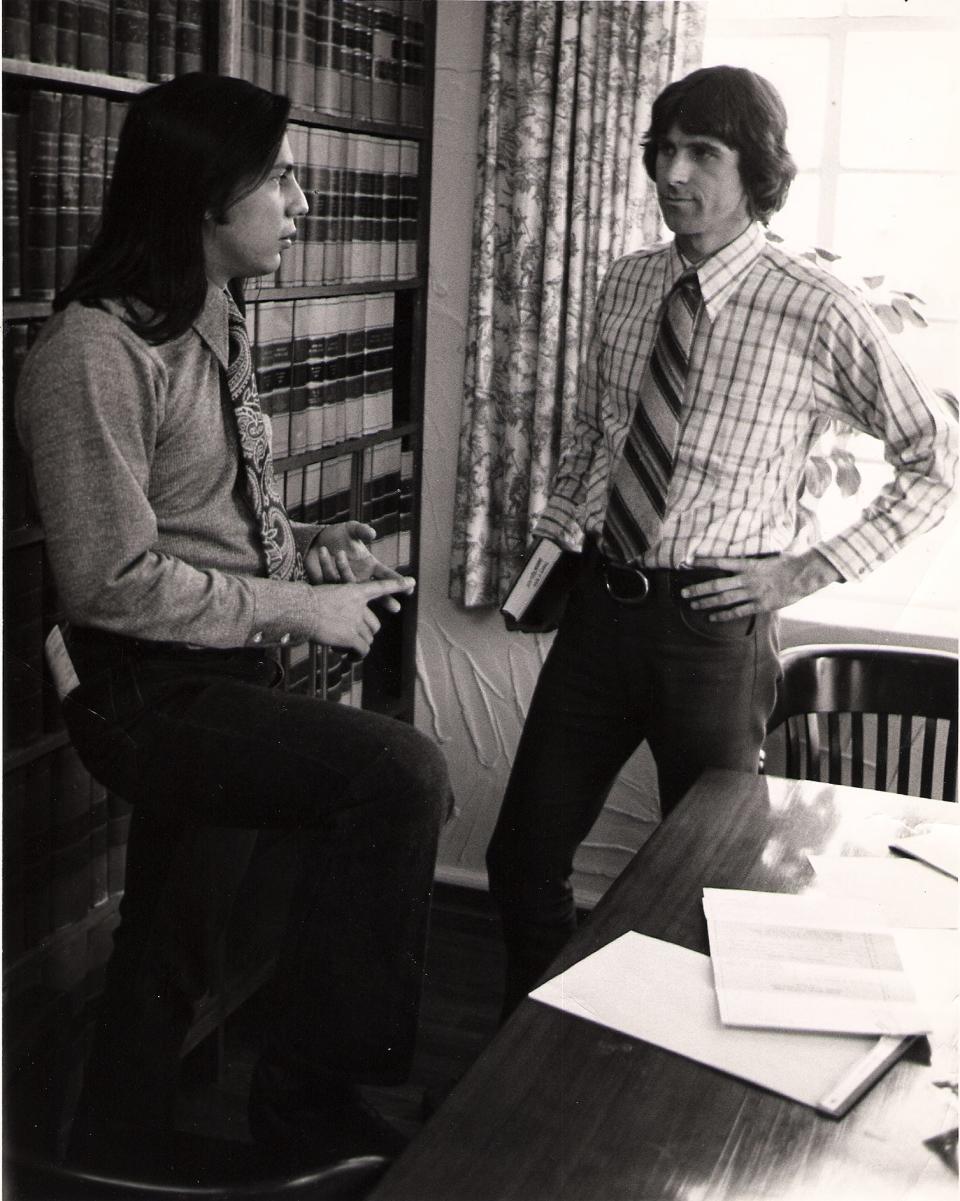

Echohawk was among a group of seven Native students who enrolled in the UNM School of Law that fall, and three years later, he walked out with his degree, ready to embark on a career that would see him land at the forefront of many of the nation’s more significant legal battles involving tribal rights over the next half century.

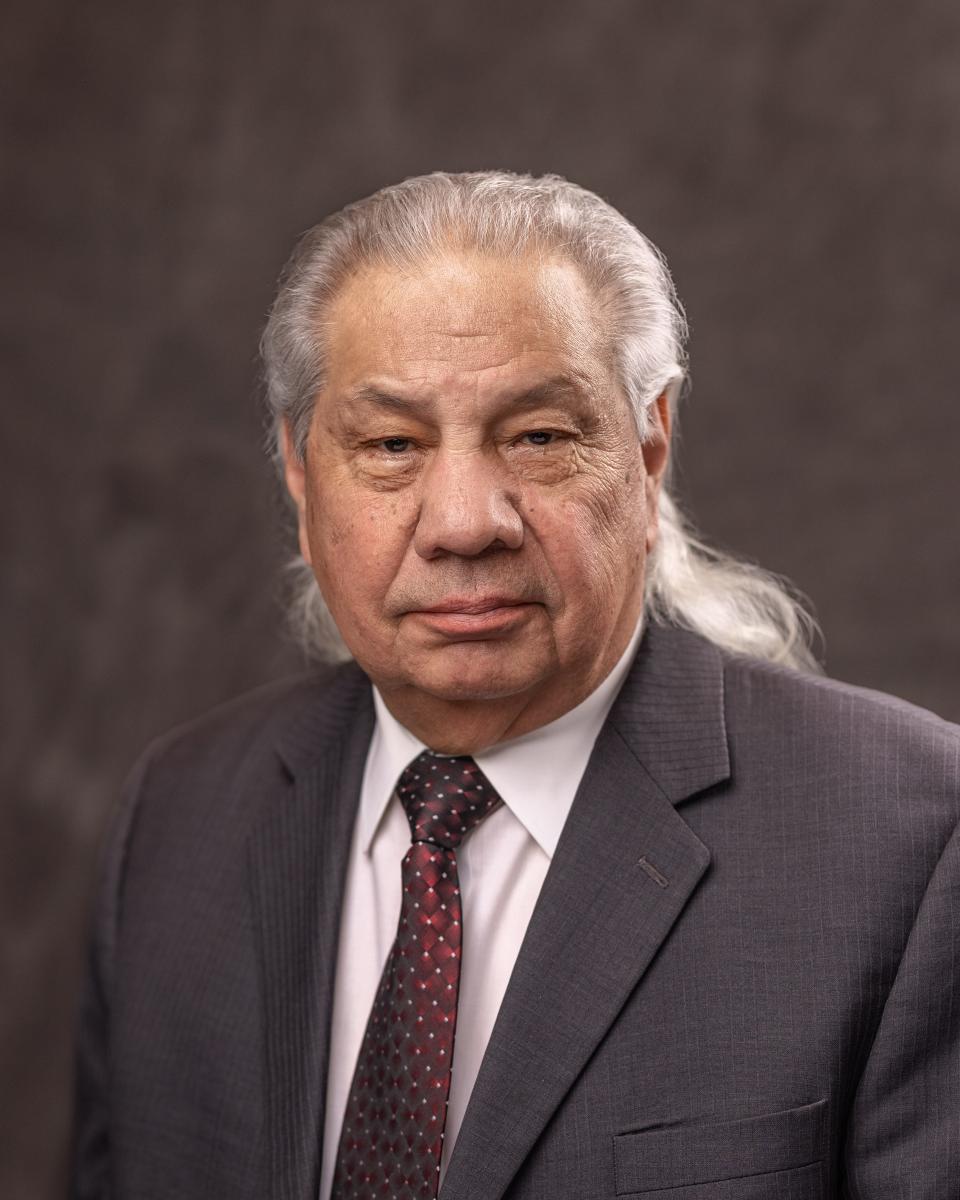

Last week, Echohawk — a member of the Pawnee Nation who has spent the last 50 years as the executive director and cofounder of the Native American Rights Fund, a Boulder, Colorado-based nonprofit organization that works to ensure that the U.S. and state governments live up to their obligations to Native people guaranteed under laws and treaties — was recognized for his work when he was awarded the prestigious Thurgood Marshall Award by the American Bar Association.

The award was established to honor the legacy of the late civil rights advocate and activist who became the first African-American Supreme Court justice in 1967. It is designed to recognize those who have served as lifelong champions of civil and human rights.

“I was very surprised and overwhelmed by the honor,” Echohawk said during an Aug. 18 telephone interview from his NARF office. “It’s just great to have that kind of recognition from the American Bar Association not only for me, but for this organization.”

Upon graduating law school, Echohawk first accepted a job with California Indian Legal Services. But only months later, a bigger opportunity came knocking — an invitation to help launch a Ford Foundation-funded initiative designed to offer legal services to federally recognized tribes across the country.

Echohawk jumped at the opportunity and helped fund the organization that would come to be known as NARF. He’s been leading the group ever since.

Almost immediately, Echohawk and NARF became involved in a lawsuit filed by a handful of tribes in western Washington who were being denied the salmon fishing rights they had been guaranteed under an 1855 treaty. State officials claimed the treaty did not specifically provide the tribes with special status and that their members needed to buy a fishing license and could fish only under the same conditions as anyone else.

“This is what they had lived on for centuries,” Echohawk said of the salmon. “It was the basis of their culture and their religion. They were being deprived of that resource by the state of Washington.”

Echohawk and other NARF lawyers successfully argued the tribes’ case, winning a judgment in district court in late 1973. A appeals court later upheld that verdict, and the tribes eventually prevailed when the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

Echohawk said it was the first domino in a series of legal victories by tribes in the 1970s and 1980s that helped them re-establish their sovereignty, which had been under attack for generations in the United States.

“It illustrated to everybody that the treaties were not some ancient agreement — they were still the law of the land,” he said, noting the decision was considered such a significant victory, its 50th anniversary will be celebrated by the victorious tribes in an event later this year.

Other wins for indigenous plaintiffs would follow over the next 20 years, and Echohawk was there for many of them. He recalled that NARF became deeply involved in the effort to reverse a U.S. government policy that prevailed throughout the 1950s and 1960s that effectively disbanded many tribes, with indigenous people who still lived on reservations being relocated to cities in an effort to assimilate them into mainstream American culture.

Echohawk said the policy was a product of 1950s McCarthyism, with some politicians considering the communal lifestyle that many Native people still led too close to communism.

“They started terminating tribal rights and selling their land,” he said.

A Wisconsin tribe, the Menominee Nation, that had been disbanded approached NARF officials and asked the organization to take up its cause. Echohawk said NARF again was successful in court, demonstrating that the federal policy had been devastating to the tribe and reinstating its status as a federally recognized nation.

NARF also was instrumental in helping the unrecognized Penobscot Nation earn another pivotal Native rights victory later in the 1970s. The Maine tribe, which had been disbanded, prevailed in district court and at the appeals court level in its attempts to regain federally recognized status and reclaim much of its ancestral lands.

With a possible date in the U.S. Supreme Court looming, Echohawk said NARF and the tribe, along with state officials, were brought to the White House at the invitation of President Jimmy Carter and encouraged to hammer out a settlement, which they did.

“The tribe came away with a lot of land back and some compensation, along with federal recognition of the tribe,” Echohawk said, noting that other disbanded tribes in the eastern United States took note of that victory and started bringing similar court claims in their own states.

Those were heady times for Echohawk and NARF, but they weren’t to last. In the 1990s, he said, the makeup of the Supreme Court changed dramatically, with many of the justices who had been sympathetic to Native arguments over the years retiring and being replaced by those who took a different view.

In 2001 alone, he said, Native plaintiffs lost four cases they believed they should have won.

“The Supreme Court was reinterpreting law against the tribes,” he said.

These days, things have become somewhat more balanced, Echohawk said, although his organization largely has adopted a strategy of trying to resolve tribal legal issues before they get to the Supreme Court.

“It’s still a very difficult situation,” he said.

The last year has seen the court rule on two significant cases involving Native rights, Echohawk said, referring to Arizona vs. Navajo Nation and Haaland v. Brackeen. The former served as a test of the Navajo Nation’s water rights, and the court ruled in favor of the Arizona government, a sobering defeat for Native rights advocates. The latter served as a challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act, a 1978 federal law that seeks to keep Native American children with Native American families. By a count of 7-2, the court ruled the law constitutional.

NARF filed amicus briefs in support of the Native position in both cases, Echohawk said.

“These issues go on, and we do the best we can,” he said, adding that over the 53 years, NARF has been in existence, it has had a profound impact. “The social and economic and political conditions of tribes have really improved. There’s been a recognition that tribal governments are part of the system of governments (in the United States).”

And that Office of Economic Opportunity program that allowed Echohawk to study law at UNM and earn his degree has had far-reaching consequences, as well, he noted.

“These days, there are 2,500 Native American lawyers,” he said. “We’re fully proportionately represented in the legal profession.”

Echohawk, who served as president of the Class of 1963 at FHS, credits many of the teachers at his old high school for encouraging him to pursue a career in law. Though he has no surviving family members in Farmington, he visited the city just last weekend to take part in his class’ 50th anniversary reunion and still holds fond memories of his upbringing here.

“That’s why I decided to become a lawyer,” he said of the support he received in Farmington during his formative years.

Mike Easterling can be reached at 505-564-4610 or measterling@daily-times.com. Support local journalism with a digital subscription: http://bit.ly/2I6TU0e.

This article originally appeared on Farmington Daily Times: John Echohawk wins American Bar Association's Thurgood Marshall Award