Farmworker advocates question poor on-farm housing

Martha Lopez has visited two on-farm housing units in her three years as a field organizer for PCUN, Oregon’s farmworker union. In the first, Lopez saw mold on the ceilings, a refrigerator that didn’t keep food cool enough, and a bathroom that one woman shared with five men. The lone female occupant confided she often asked her husband to stand watch while she bathed.

More: How we reported this story on farmworker housing in Oregon

The second was dirtier, more run-down, Lopez said. But her observations were from the outside. The men who lived there didn’t invite her in.

Agricultural workforce housing, which is generally shared housing accommodations provided by farms as a benefit and condition of employment, was a staple of migrant farming during World War II and into the 1960s.

Now, it houses a shrinking proportion of farmworkers, often for short periods during harvest season.

But people who use and supply agricultural housing say the system isn't working as it should. And regulations that govern agricultural housing still allow for undignified living situations: portable toilets instead of indoor plumbing, cramped quarters, outdoor kitchens or none at all.

Labor advocates say such housing isolates workers, reduces them to their labor and strips them of their dignity.

Farm operators who provide the housing say current regulations are cumbersome, unclear and ill-enforced.

Oregon OSHA, the state agency in charge of housing registration, rulemaking and enforcement, is in the early stages of reviewing and updating its labor housing rules. Whether it will create new rules or tighten current ones is yet to be determined.

Permanent laws about agricultural housing have been updated twice since in the last decade – once in 2018 to address pesticide exposure, and once last year as part of Oregon OSHA’s permanent heat and smoke rules.

Labor advocates say the update is overdue and are asking the agency for more, and stricter, regulations. Growers fear the cost associated with such changes.

There is agreement, however, that if the state is going to create new rules, it must also more strongly enforce the ones it already has.

Lopez’s job is to meet with farmworkers, hear their concerns and tell them what resources are available. Still, the visits to workers at their homes stuck with her.

“I didn’t know those things happened,” she said. “That there were people that lived in that type of place and lived in those conditions.”

Farm labor housing 'a unique situation'

Any agricultural producer who provides housing to employees as a benefit of employment must register their housing with Oregon OSHA.

According to the agency’s database, some 400 registered housing sites shelter about 10,000 agricultural workers throughout the year, roughly 8-10 percent of the state's workforce.

Labor housing as a system is remnant of the "Bracero" program, which brought migrant workers from Mexico to work on U.S. farms during busy seasons beginning in 1942. Federal regulations about farm labor houses were enacted in 1949 in response to allegations of abuse against Bracero program workers.

Farmworker housing was intended to house migrant workers who followed work depending on the season. That is still its primary purpose. Growers say they wouldn't have a seasonal workforce if they didn't provide housing.

Farmworker housing is classified in two ways: as H2A housing, which is reserved for seasonal workers from other countries working under the H2A visa program, or non-H2A housing, which is meant to house domestic workers.

Agricultural employers operate under a different set of rules than, say, a homeowner who leases their property. The seasonality of farm labor has given farmworker housing the moniker "labor camps." Most units are dorm-style complexes, or bunk houses, designed to accommodate multiple workers.

It's not just workers who use them.

A playground at one housing complex's play area, just outside a barn-red building with half a dozen doors, sits atop a bed of cherry pits. They’re small, round, and as soft and absorbent as bark. The pits came from cherries grown at Orchard View Cherries and processed in The Dalles.

Orchard View stretches more than 3,000 acres through the hills of the Columbia River Gorge. Its housing is immense: more than 1,600 beds are spread across more than a dozen units.

The play structure is evidence that residents here are not just workers, but their kids and families, too. Orchard View knows that, and even prefers it.

“We house families, not just people,” Brenda Thomas, Orchard View president, said.

Orchard View considers its housing facilities “above average,” Omeg said.

They know not everyone can afford the amenities Orchard View provides – including a full, regulation-sized soccer field they spent $20,000 to level, and play structures at every unit.

It costs more to house families, rather than just workers. But it’s worth the cost, Mike Omeg, Orchard View director of operations, said.

Families at Orchard View live there for roughly two months during cherry harvest season, from late spring to early summer. That isn’t long enough for most workers to find housing in The Dalles, a community already stretched for housing. So employers like Orchard View provide it, for free.

Growers say on-farm housing serves a different purpose than permanent, residential housing and regulations should reflect that.

“Labor housing is a unique situation,” Omeg said. “It needs to be treated as such.”

Omeg, Thomas and operations manager Ann Billette are proud of the housing they provide to workers and their families. And they want their employees to feel proud to work there.

They acknowledge not all growers invest so much into the housing they provide.

A different set of housing rules

Oregon OSHA’s 20 pages of agricultural housing rules are designed to account for high occupancy: at least one shower head, with hot and cold water, must be provided for every 10 people. Bunk beds are allowed as long as each occupant has at least 40 square feet of sleeping space (“no triple bunks,” the checklist clarifies, in parentheses).

Oregon residential code, which is used by many municipalities including Woodburn, where many Willamette Valley farmworkers live permanently, is hundreds of pages of technical language and building regulations.

“There are rules that are less than [local] residential codes” for on-farm housing, Ira Cuello-Martinez, interim executive director at PCUN, said.

Toilets, for example, can be chemical or portable, as long as they are cleaned and maintained regularly and “within 200 feet” of the living space.

Kitchens, if provided, can be outside. Employers can provide a stove or hot plate. If they do, they must provide two burners for every 10 people.

Some of the housing units at Orchard View have outdoor kitchens. It’s not ideal, Billette said, and they’re working to move all kitchens inside. Outdoor stoves are under a covered porch, protected from the elements, and are only used during the summer months. It was the only way they could meet capacity regulations and house as many people as they needed to, Billette said.

They also agree with labor advocates like Cuello-Martinez that there’s a difference between minimum health and safety standards and quality of life.

They disagree, though, on who should regulate quality of life. Some things, Omeg said, should be discretionary, not mandatory.

To those who see it at its worst, farmworker housing is a dignity issue. Even housing that complies with OSHA's standards doesn't always provide a dignified home environment.

Cuello-Martinez said seasonality should not be an excuse for poor living conditions.

“It’s still a place where people live,” he said. “It’s a place for human beings, who deserve a dignified job and home.”

OSHA ag housing inspections effective but infrequent

Before COVID-19, Billette said, Oregon OSHA visited every year to inspect or consult.

But since the pandemic, Oregon OSHA’s visits have waned.

The Statesman Journal filed public records requests and then analyzed five years worth of on-farm housing inspections and violations.

In 2019, Oregon OSHA performed 50 inspections at registered on-farm housing units, according to data obtained by the Statesman Journal.

In 2020, Oregon OSHA performed seven inspections. And inspectors have yet to catch up to pre-pandemic numbers. Oregon OSHA has performed fewer inspections in the past three years combined than in 2019 alone.

Those numbers are only part of the story, Oregon OSHA spokesperson Aaron Corvin said. The agency had to quickly pivot to make new rules to protect workers from COVID-19, communicate those rules and enforce them to the best of its ability.

"There is no question that COVID-19 reduced our overall enforcement activity – not just our enforcement activity with respect to ALH (ag labor housing)," Corvin said.

Until recently, he said, the bulk of resources were "directed at reducing the risks to workers of COVID-19 in the workplace."

Corvin said Oregon OSHA "successfully handled" more than 30,000 workplace complaints, across all sectors, throughout the pandemic. The agency typically fields about 2,000 complaints a year, Corvin said.

Oregon OSHA conducts some on-farm worker housing inspections based on complaints or referrals, either from other agencies or from employees themselves. But it also has an inspection schedule it maintains every year.

According to Oregon OSHA guidelines, the agency schedules inspections based on whether a registered housing facility has been inspected in the past 24 months. That does not mean it is trying to inspect each registered housing unit every two years, Corvin said. To do that, the agency would have to conduct roughly 200 inspections per year.

Instead, Corvin said, OSHA's focus is on "allocating ... enforcement resources in a way that enables us to visit locations that are in use and that have not yet been visited."

Guidelines for H2A housing mandate annual inspections before occupants arrive.

Non-H2A housing is a "dynamic situation," Corvin said, that doesn't adhere to such schedules. Some units are occupied year-round; some are occupied for months or weeks at a time. In some cases, multiple employers operate the same housing location at different times of the year.

A housing complex in Mt. Angel, for example, is registered to Catholic Community Services and six different agricultural operators. Catholic Community Services manages the property, a spokesperson said, and different employers offer it to employees in different seasons.

Oregon OSHA conducts in-person consultations prior to initially registering a labor camp. Growers are required to renew registration every year and continue to meet the state's regulations.

Consultations are another tool for checking on the conditions of agricultural labor housing, Corvin said. But Oregon OSHA's guidelines say consultation priority should be given to H2A operators or new housing units, and "operators who request consultations every year will be placed on a low priority and only provided consultation services as time permits."

Housing providers also are required to report if they make any significant structural changes to the property, which would trigger an inspection.

Inspection records show it is more likely that registered housing with a documented, serious violation will make it onto the agency’s inspection schedule within 24 months. Since 2018, 10 violations (out of 400) are considered “repeat.” Each offender has been inspected again within two years.

Concern about problems OSHA is missing

Inspections do yield results. More than half the violations reported since 2018 were caught during routine, scheduled inspections.

But a majority of “serious” violations Oregon-OSHA has recorded since 2018 were based on complaints or referrals. They were caught because someone reported the employer or the facility.

Growers and labor advocates alike say they’re concerned about the problems OSHA is missing. Oregon Law Center has dozens of photos of unsafe, dilapidated housing units outreach workers have seen. It includes broken or missing windows, mold, mattresses on floors.

And there’s danger in trusting a complaint-based system, Lopez said. Employees may fear retaliation.

Workers are legally protected from retaliation if they report their employer — a fact Corvin said OSHA works hard to communicate.

Lopez said she has heard stories of farmworkers filing complaints and ending up on an unofficial blacklist.

“There are people who have told us, ‘I reported, and then my photo was shared with contractors and I don’t have work,’” Lopez said. “There’s still fear.”

And the stakes are higher when housing is attached to employment. So, Lopez said, plenty of workers stay quiet.

Gov. Kate Brown commissioned an agricultural housing task force last year to address issues with agricultural housing and propose solutions.

One of its recommendations was to improve communication between agencies so other agencies that interface with agricultural housing, like the Department of Agriculture or the Bureau of Labor and Industries, can identify and report any possible violations.

Improved interagency coordination would help fill the gaps in Oregon OSHA’s “limited resources,” the task force determined.

Oregon OSHA has 85 inspectors agency-wide. Not all of them conduct ALH inspections, Corvin said. Regional field managers prioritize workplace inspections based on risk. The higher the perceived risk, the higher the priority.

Marion County accounts for a small portion of on-farm housing in the state and an even smaller portion of violations. Twenty-one out of 382 recorded violations since 2018 were reported in Marion County. Only three of those violations, all at Northern Lights Wreath Company in Silverton, were considered “serious” and resulted in fines.

Unregistered housing suspected to be the worst

Unregistered housing that growers don't register or let their registration expire came up frequently in task force meetings.

"I can't stress enough: The places that aren't registered, we need to get to those places," OSHA administrator Renee Stapleton said during a fall meeting.

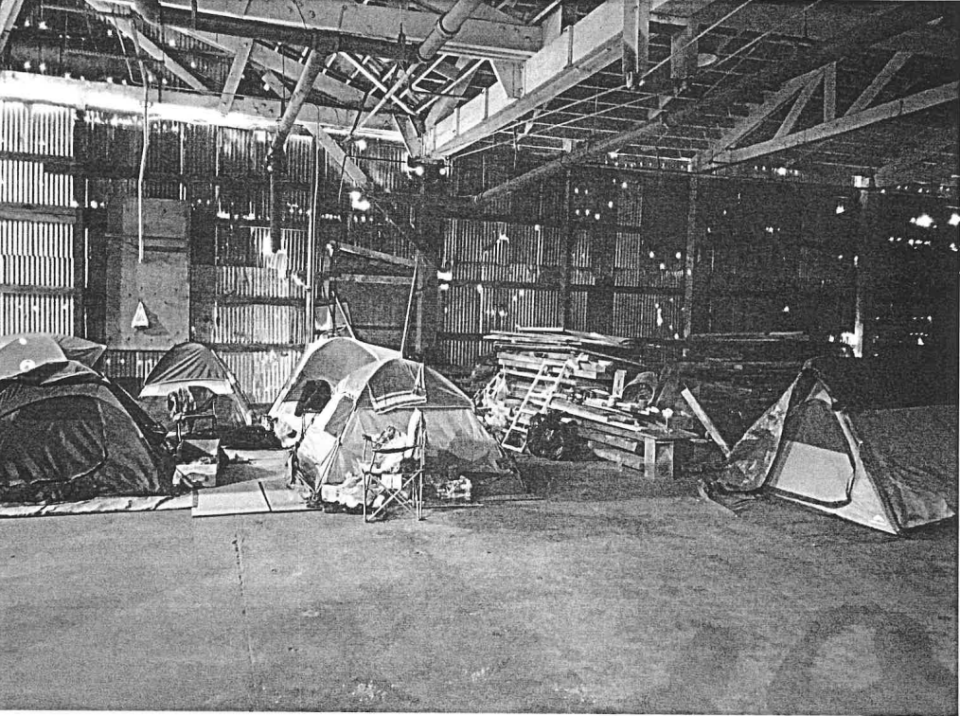

Indeed, the highest penalty in recent years, $825,000 split evenly among five employers, was given to hemp operators in Josephine County who housed workers in a condemned building. The facility was not registered and the building — a shed with holes in the roof and one useable exit — had been deemed "structurally unsafe."

Corvin said unregistered housing is a "priority" for Oregon OSHA. Operators who don't follow registration requirements are "likely already outside the boundaries of other requirements."

They also are harder to find, so complaints and referrals become especially important. Corvin said OSHA makes "every effort" to respond to allegations of unregistered housing "as quickly as possible."

Growers like Meyer and Omeg said cases like the one in Josephine County are unacceptable. Oregon OSHA should "shut people down" for that, Omeg said.

Updates coming to OSHA's housing rules

Oregon OSHA is in the early stages of updating its agricultural housing rules.

Corvin said the ALH Advisory Committee will meet "regularly" this year — meetings are scheduled for the last Wednesday of every month — and propose rule changes in 2024.

In public meetings and interviews with the Statesman Journal, advocates said it's time for big changes.

One of the rules advocates want is a blanket requirement to provide air conditioning in each unit.

The current heat and smoke rules dictate all housing facilities must have a “cooling area” where employees can cool down. That area can be a common room with air conditioning or good ventilation or a shaded area outside, as long as at least half the occupants can use it at any time.

Employers also must protect windows from direct sunlight and make fans available for anyone who wants them.

It’s not enough, advocates say. Farmworkers have recorded bedroom temperatures of more than 100 degrees even in the early morning hours — too hot to sleep comfortably and recover from a day's work.

But big, structural changes require money growers say they don’t have.

High Rolls Ranch and Orchard View Cherries both provide air conditioning in all their units. After Oregon OSHA issued its permanent heat rules, Orchard View spent roughly $100,000 to update the electrical systems in its housing units to accommodate AC, Omeg said.

But labor advocates say the cost of providing safe, humane housing is one growers should be prepared to cover.

“If you can’t afford it, you shouldn’t have it,” Cuello-Martinez said.

Part of Gov. Tina Kotek’s housing package includes $5 million to help growers improve existing on-farm housing.

It’s a start, Omeg said. But a farm the size of Orchard View could spend the state’s entire budget itself and still have work to do.

Farmworker demographics and housing needs are changing

On-farm housing is remnant of a time when most farmworkers were migrant and seasonal.

That is no longer the case in Oregon.

Most farmworkers — roughly 80%, by Oregon Law Center’s estimation — are permanent residents of their communities. Their housing needs are different.

Cuello-Martinez said his ideal scenario is one in which no farmworker has to live where they work. Instead, he said, the state should direct resources to organizations like the Farmworker Housing Development Corporation, FHDC, which builds low-income and farmworker-specific housing.

FHDC owns 11 community-based housing complexes, including its newest, Colonia Paz, which opened last summer in Lebanon, Oregon.

Rent for a two-bedroom unit is capped at $722 per month, property manager Mario Carbajal said at the complex's grand opening. It cannot exceed 30% of the household’s income.

Lopez lived in one of FHDC's housing units. It’s how she got her current job at PCUN, she said. FHDC provided childcare and free education, all of which helped her get where she is.

A bill in the Legislature would allocate $10 million to community-based farmworker developers like FHDC — down from an original proposal of $20 million.

Maria Elena Guerra, FHDC’s executive director. She attends agricultural housing facilitation team meetings and is vocal about paying more attention to the kind of housing her organization provides.

It’s frustrating, she said in an interview with the Statesman Journal, that money for on-farm housing passed “with not much effort,” but House Bill 3555 was cut in half and awaits its fate in the House Ways and Means committee.

“Here we are, with all the benefits we provide to a community, to an entire system, and we still have to prove that it’s needed,” Guerra said. “I didn’t hear that happening for on-farm support.”

But Omeg and Meyer say they wouldn’t have a workforce without seasonal workers, and they wouldn’t have seasonal workers without seasonal housing. “For seasonal employees, community housing is not a viable option,” Omeg said.

Shannon Sollitt covers agricultural workers through Report for America, a program that aims to support local journalism and democracy by reporting on under-covered issues and communities. Send tips, questions and comments to ssollitt@statesmanjournal.com

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Farmworker advocates question poor on-farm housing