When My Father Died, I Felt Relieved. But An Unearthed Childhood Photo Has Me Wondering More.

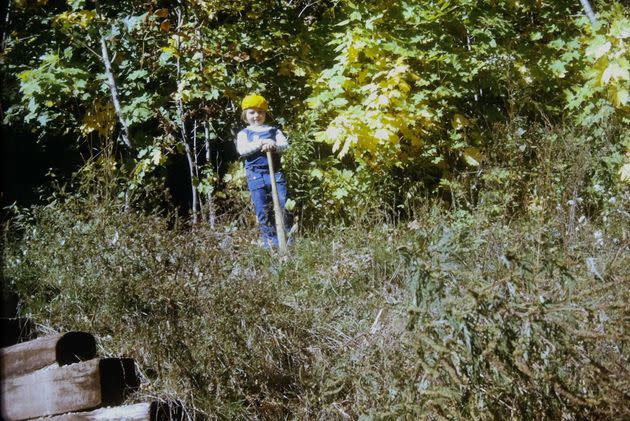

"1975 was not the greatest year for children's fashions but I was trying my best to be a stylin' baby butch." (Photo: Photo Courtesy Of Kelli Dunham)

I am the fifth and final child born into a struggling rural Midwestern family. My mom reports that I was so active in utero that she knew she was having “a boy or a heaven-help-us girl.” I identify as nonbinary now, but “heaven-help-us girl” is probably a more accurate description of my gender.

Like a sitcom character sent from central casting to portray The Kid Who Would Wreak Havoc, I emerged as a fully formed, sensitive, opinionated coastal genderqueer.

Starting at age 7, I asked to be a vegetarian (in ’70s farmland Wisconsin), to which my mother replied, “What on earth would you eat?” One Sunday afternoon, I spent three hours following my mom around from room to room, pestering her about what we could do to keep harp seals from being clubbed. She just wanted to clean her house.

When it rained, I regularly missed the school bus. I would be delayed by my quest to prevent worms from getting run over by returning each of them from the pavement onto the grass.

My third-grade teacher gave us an art project that undid me completely. She put her 45 record of Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” on repeat and told us to draw the story. As I attempted to crayon the capsized boat with the sailors spilling into the water, the lyrics caused me to break into protracted sobs so intense that the teacher frantically scheduled a conference with my mom.

While my mom was summoned for these (and many other) crying-related emergencies, my dad unraveled in frustration in response to my inexplicable, insistent and highly inconvenient tenderhearted antics.

If Archie Bunker, the Great Santini and Matt Foley, motivational speaker, somehow overcame biology and their status as fictional characters to produce a child, that offspring would be my father.

He was an almost ludicrously stoic man who was raised on a struggling farm near the struggling town of Caro, Michigan, by an even more stoic and also struggling father. He often bragged that he hadn’t ever seen his father smile.

The ’70s self-help classics like ”How to Win Friends and Influence People” and ”Winning Through Intimidation” enthralled him. He would signal the beginning of breakfast (always at 6 a.m.) by slamming his fist on the table and announcing, “Act enthusiastic, and you’ll be enthusiastic!”

He would then add, “Most people are just about as happy as they make up their mind they’re going to be,” a quote he alternately attributed to Dale Carnegie and Winston Churchill, which seemed aimed directly at me.

But I wasn’t unhappy,

I was just worried about the worms.

And the harp seals.

And the whales.

And the widows of the Edmund Fitzgerald crew.

I also really, really, really really didn’t want to wear a dress to school, even on picture day.

Concerned about — and inevitably annoyed by — behavior he found inexplicable, my dad would attempt to head off a sob attack by asking, “Oh, are you gonna cry now?”

Since the answer to that question was nearly always yes, it’s curious that he never reconsidered the effectiveness of his behavior modification technique.

My mom always informed us, “Your father never struck you in anger,” and although that particular narrative doesn’t match my historical recollection, I prefer my version. If you’re going to get hit, “I’m mad” seems like a better reason than, for example, “It’s Tuesday.”

My father was a lifelong smoker. When I was 12, he developed lung cancer. I knew I was supposed to be worried ― and I felt sad to watch him suffer so much from ultimately futile treatments — but the weaker he got, the less afraid I felt.

When he was sick, I felt ambivalent. I was heartbroken for his physical anguish. But each chemo treatment he underwent made it less likely he’d explode across the dinner table for an offense only he understood — drinking in between bites of food was an inexplicable and random pet peeve ― eventually leaving me with a bloody nose or much much worse.

When he died, the ambivalence was replaced with relief. There was relief for him, that he was no longer suffering. But there was also ease in simply feeling safer. The man who had once beaten our 125-pound Newfoundland dog with a two-by-four didn’t live in our house any more. The constant creeping fear of “Could I be next?” was gone.

And then I felt guilt for feeling relief.

I wouldn’t say the Germanic culture of rural Wisconsin during the ‘70s particularly helped me develop the ability to read other folks’ emotional cues. Still, as near as I could figure, it seemed my cisgender, less emotionally soggy siblings who were much less likely to become a focus of my dad’s anger and my mom all missed him. Maybe even a lot.

I pretended to be mildly sad; it seemed impolite to be less concerned about the death of my flesh and blood than a harp seal I had never met.

“You’re very brave,” said my seventh grade physical education teacher when I returned to school and didn’t mention my dad’s death, even to my friends.

“Sure,” I thought, “let’s call this brave.”

I guarded my grief secret closely until I was in my early 40s. A new friend heard me reference one of my more unsavory memories of my father, and she brightened up.

“Oh, you’re part of the Glad Dead Dad club too?” Being asked that question loosened decades of guilt that had been tight like a band around my chest. The Glad Dead Dad’s Club is not a large club, perhaps, but I was extremely relieved to discover I was not the only member.

I took to social media the following Father’s Day and shared, “had a great day courtesy of my dad’s death from lung cancer when I was 12. I should write Philip Morris a letter. I bet Big Tobacco doesn’t get a lot of thank you notes.”

It wasn’t the world’s most nuanced post (and frankly not the most well-received), but it was a relief to be open after spending years feeling like I was a villain in a Disney animated movie. We didn’t have a simple relationship. Why would I expect my feelings in response to his death to be uncomplicated?

Then last year, my older sister patiently scanned 2,000-plus pictures my dad had taken during the last 30 years of his life. She emailed me a link to the massive online photo album site with a note, “I think I found the cover image for your next comedy album.”

I clicked through the site. There were countless images of trees damaged by ice storms, our Ford LTD station wagon looking small next to giant snowdrifts, children looking small next to giant vegetables, and a large slobbering outdoor dog we should have taken much better care of. When pictures captured groups of adults, each person would have a cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other.

Then I found the photo she was referencing.

Although I was wearing my brother’s hand-me-down baseball cap and carrying a bat, I was not playing baseball. I was hanging out in the woods, building a fort, and living my best life.

(Photo: Photo Courtesy Of Kelli Dunham)

I don’t have a specific memory of my dad taking this photo, but he didn’t habitually carry his camera, so he would have had to stop whatever chore he was doing and get his camera, film, and flashbulbs from the house to capture this moment. It doesn’t seem like a behavior sequence motivated by annoyance. It felt like a picture taken by someone who really saw this kid.

Whenever I refer to my parents as the cliche “doing their best,” my Slightly Sarcastic New York Therapist will say in her Slightly Sarcastic New York Way, “Hmmm. Really. So that was their best.”

They would perhaps not be shortlisted as candidates for parents of the year now (or in the ’70s), but within their context, given their skills and resources, they certainly could have done much worse.

This photo made me wonder how much more of me my dad indeed saw but didn’t have the emotional language or experience to communicate. What could have happened between my father and me if he had lived and been given access to any tool to improve his relationships: therapy, the 12 steps or, in a pinch, even AITA on Reddit?

Not that my dad would have become the kind of parent who has an ironic handlebar mustache, brews his own kombucha and gives his children multiple choices about what brand of organic yogurt they’d prefer. But in a world where my dentist asks about my pronouns and Target carries transmasculine packing underwear, perhaps he could have at least been proud of the sensitive, not-a-man, not-a-woman that I’ve become.

My grief for my dad is still complicated. Because I’m so grateful for the years of safety his death provided for me, it would be disingenuous to turn in my membership card for the Glad Dead Dad’s Club. My tears — which, of course, would make him bananas ― reflect my sadness for both of us, and our collective missed potential opportunity to know and be known.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.