My Father Fled Nazis in Austria—I’m Becoming a Dual Citizen

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I did something recently that would have been inconceivable to me at almost any point prior to the past several years of my life. I—born in America’s heartland, a former U.S. government official, someone who has devoted most of his adult life to grappling with questions of how you make this country better and stronger—became a citizen of another country. I did not and would never give up my U.S. citizenship. But now, I have two passports, one U.S. and one Austrian.

Let me explain, which requires a little back story and then some reflection on the times in which we live.

My Dad was an athletic man. Nearly six-foot-two. He played tennis and lifted weights well into his eighties. Then, an old kidney ailment related to his childhood poverty and malnutrition in Nazi-controlled Vienna forced him into dialysis. A decline began that made it impossible for him to walk. For someone who had been so active his entire life, immobility was a jail sentence, intolerable.

He fought it as best he could. He would write every day and beneath his desk he kept a small exercycle that he could slowly pedal as he worked. He did physical therapy. He applied his great scientist’s brain to finding a solution to the problem of the weakness in his legs. He was dogged but it was a losing battle. Gradually, his thoughts turned from practical solutions to some that were more far-fetched.

My father, Dr. Ernst Zacharias Rothkopf

One day I went into his room at the local rehab center where he was being put through intensive but frustrating daily workouts with specialists. It was a drab place, all beiges and muted moss tones. He had a semi-private room with a view of a parking lot and some dried out lawn beyond which there were a few trees. But as I approached, he waved me over to his bed with more animation than I had seen from him in a while.

Across the bed were spread colorful brochures. Almost all offered scenes that could not have contrasted more strikingly with the view from the bed to which he was confined for most of each day. There were deep blue skies and soaring, snow-topped Alpine peaks. There were mountain-top meadows and crystalline lakes. He held one such brochure up to me and explained his latest plan.

The pamphlets were all for spas that offered curative waters and promised specialized, rejuvenating care. The one he showed me was in the Tyrol. He described his goal. He wanted to be able to walk 50 steps. Then he could be taken to an airport, wheeled to an airplane where he could stand and walk to his seat. He would fly to Austria and the spa said it could arrange his pick-up and transport to them. There, he hoped, in the mountains of the country of his birth, he would find new hope and possibly a new lease on life.

His optimism was heartbreaking. On some level he knew it was nothing but a fantasy. But beneath it was something else, something mysterious to me. Born in Vienna, his childhood had been far from easy. His family was desperately poor. They often had little food. At times his mother would have to divide what there was for a meal between my father and his father and she would go hungry. The bathtub was in the kitchen.

Following the Anschluss in March 1938, when my father was 12, things got much worse. With Austria annexed to Germany, Jews were persecuted. He got scarlet fever and was relegated to a hospital where he was forced to share his bed with another Jewish boy. That boy died on a Friday night and my father had to lie there beside him until doctors took him away the next day.

On Kristallnacht, my grandfather disappeared and my father searched the city for news of him. While my grandfather did not appear again for several days, my grandmother and my Dad feared the worst but fortunately, the family was reunited soon after. My father was to have been bar mitzvahed a few weeks later but that never happened because the synagogue was burned to the ground.

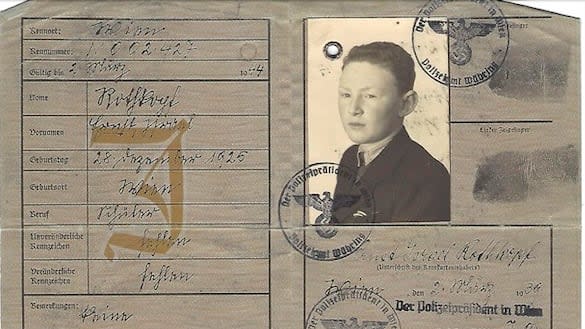

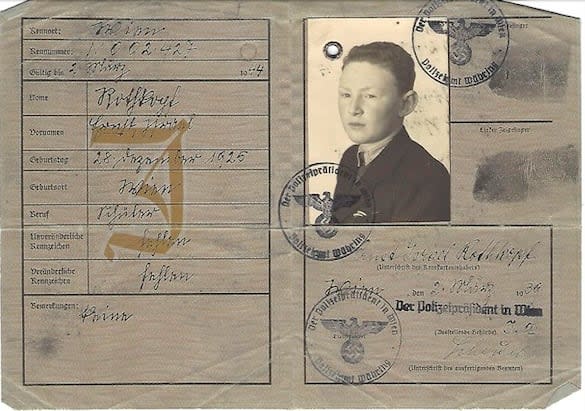

A Nazi-issued ID card for my father, marked with a "J" for "Jude"

Later, they desperately tried to find a way to leave, a feat they did not accomplish until December 1939, at literally the very last possible minute. They escaped by train and on foot and then by Liberty ship to New York and ultimately to Danbury, Connecticut, where my grandfather’s brother lived.

My father was an enthusiastic American. He learned English by going to the movies for a nickel each weekend. He watched short subjects and a double feature and got a plate or a glass to bring home to his mother. He entered basic training and later Officer’s Candidate School in Texas and Oklahoma. There he developed a lifelong love of the West and deserts and local expressions. He liked to refer to certain people, with his not so subtle accent, as “yay-hoos.”

My father in St. Mark's Square in Venice, in 1945

During the Holocaust, as over three dozen relatives were killed as were most of my father’s childhood friends, my father served in the war as an artillery officer. He was deployed with the 88th Infantry Division, the Blue Devils, in Italy. Family whispers suggested perhaps at some point he participated in a secret mission to rescue the Crown of St. Stephen in Hungary. We may never know for sure. But we do know that after the war, while still in the Army, he visited concentration camps looking for records of lost relatives. One aunt had the misfortune to live with her husband and children in Oswiecim in Poland. In German, the town was called Auschwitz.

Throughout the decades following his return from the war, as he worked at Bell Telephone Laboratories and as a professor at Columbia, he was extremely patriotic in every imaginable way. As a scientist he often worked with the Navy and the Air Force. We displayed a flag on national holidays. He spoke with great pride of being an American, of what he owed to this country.

But for all of this, despite the unimaginable horror and traumas of loss and dislocation, Austria had a hold on his heart. On his birthdays, his mother would make Wiener schnitzel and cucumber salad and sometimes a Sachertorte would be shipped to us in a fancy wooden box for dessert. He visited Austria several times and closely followed developments in that country. He took us there and even though my brother and I were little at the time, I remember his pleasure in showing us the city, from the Schönbrunn Palace and the Riesenrad, the giant ferris wheel located in the Prater Amusement Park. He spoke often, throughout his life, to one of his surviving boyhood friends, a man named Paul after whom my brother was named, who had remained in Vienna and became a prosperous furrier and for a time, head of the Austrian chapter of the World Jewish Congress.

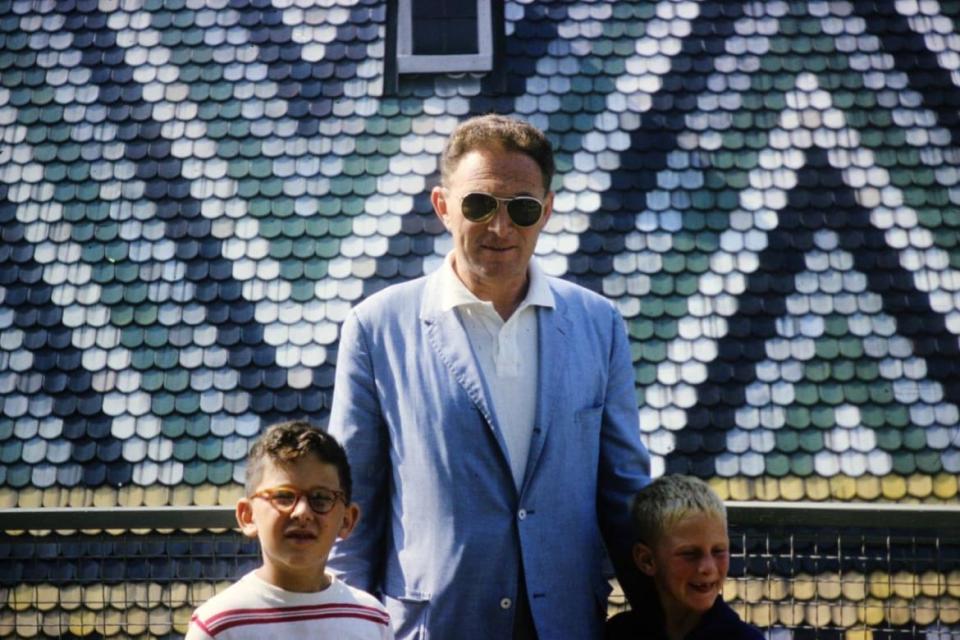

My father with my brother and me

My Dad sometimes listened in his office to Austrian composers and even to the martial music of Austrian marching bands. He spoke fondly of following the Austrian soccer team’s exploits in the 1934 World Cup. He was essentially, irreversibly—despite everything—Viennese. And as my story indicates, he remained so, until his death almost a decade ago.

Last September, the Austrian government introduced a new law that made citizenship available to the direct descendants of all who had fled the country under Nazi persecution. After double-checking that U.S. citizens could hold dual citizenship (by the laws of both countries), I approached my daughters (who actually had not one but two Austrian grandfathers) and asked if they would like it if we applied.

The benefits of EU citizenship seemed great. But honestly, I was motivated by something deeper. I felt it was something that would mean a lot to my father, that would keep part of him, of who he was, alive not just for me but for my daughters and ultimately for their children.

That is not the whole story of my reasoning, however. As dark as my father’s history in Austria had been, I had come to see echoes of his story in the United States. For years, I had known about and felt periodic antisemitism. (You can only imagine the horror and sadness in my father’s eyes the first time he saw swastikas drawn on our driveway in suburban New Jersey back when I was still a small boy. I know I won’t forget it.) But since the election of Donald Trump, things had gotten much worse.

If I had been attacked for being a Jew a few dozen times in my entire life prior to 2016, once Trump began his racist, ethno-nationalist reign of hatred the total skyrocketed. On social media and elsewhere I got death threats and endured the worst sort of hate-filled attacks on a regular basis. Whenever I spoke out against Trump, I was marked with triple parentheses and sent pictures of Auschwitz ovens and even, most disturbingly, on a couple of occasions, attacks that mentioned my daughters.

The president of the United States was promoting and by extension giving permission to others to spread the kind of hatred and division that echoed that which my father had heard as a child.

Eventually, those threats were compounded by something equally odious. Trump and his enablers in the GOP leadership launched an attack on democracy in America. They sought to place the president above the law. They obstructed justice. They showed contempt for separation of powers and the Constitution itself. It was clear years ago that if they had their way, they would gut democracy in this country to preserve the power of their benefactors and the racist minority they were exploiting to gain political clout. It became increasingly clear that they were willing to resort to violence and cheating to have their way.

Gaining dual citizenship would be a tribute to my father but it would be more than that. It would be a reflection of lessons learned in his lifetime. Sometimes the unthinkable happens. Sometimes, the seemingly impossible can become a sudden, bitter reality.

As we went through Austria’s application process—which was long and required finding documentary evidence of what happened to my father and his family—the situation in the U.S. grew more dire. There was the big lie and then there was the attempted coup. And then, just as disturbingly, there have been the months since in which the GOP came to embrace and defend that attack on democracy.

Trump’s Big Lie Isn’t About 2020 but All the Elections to Come

Today, as evidence compounds that Trump and Co. were engaged in a long-standing, well-funded, well-organized attempt to steal a U.S. election, there is still no accountability for the former president. Indeed, his loyalists remain lined up behind him and celebrate his crimes.

With voter suppression on the agenda in scores of states across the country and courts packed to protect these blatant, often racist, power grabs, the situation today is worse than it has been at any time in the Trump presidency. It is worse than it was on Jan. 6.

If we fight, and if the Department of Justice lives up to its responsibility to defend the Constitution and the principles which underlie it, then we may yet save this country and our democracy. Personally, I will work toward that goal every day I can with every ounce of energy I have.

But this battle is far from won. Indeed, at the moment, in key ways the threat is greater than ever. And frankly, I would not be a good father nor would I be responsible in light of the experience of my family, if I did not acknowledge that. We have seen stories like this one before in places where they also said “It can’t happen here.”

It is my fondest hope that ultimately my children and I look at our dual citizenship as a tribute to our forebears and as a way to celebrate an important part of who we are. But if I were to say that was the only reason we have pursued this path, that would be a lie—and one that would underplay the warning I hope all of us will acknowledge and the urgency of the fight to preserve what is best about America that I hope we all will undertake.

There is at the heart of this a dark irony. Which is, in case you missed it, the point of this story.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.