He was the 'father of Indianapolis schools,' but there's a century-old error on his grave

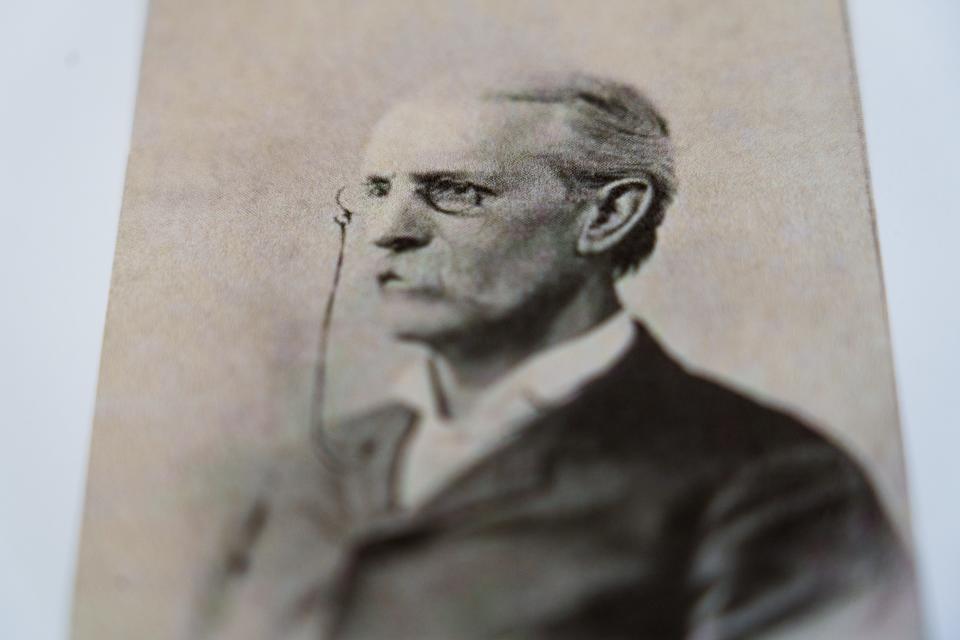

Abraham Crum Shortridge was, to say the least, an esteemed educator. He was the powerhouse behind the success of the city's first public high school, the steady leader Purdue University selected to oversee its opening, the man deemed the "father of Indianapolis schools."

He died in 1919 and was laid to rest in Crown Hill Cemetery, not far from the renowned company of former President Benjamin Harrison and writer Booth Tarkington. But Shortridge's own gravestone — the one physical place where people can pay their respects — has long fallen short of an educator's standards.

It spells his name wrong.

Instead of "Abraham," it reads "Abram" in raised letters that can't be altered to accommodate the correct moniker. It's enough to rankle the historian whose research prompted current notice of the error in the first place.

"It just irked me no end," said Sharon Butsch Freeland, a 1965 Shortridge High School graduate and member of the alumni association's board. "I come from a family of several generations who went to Shortridge High School, and I just had to do something about it."

So with Abraham's descendants' permission, she started a GoFundMe to raise $5,000 for a new stone that will give him his due.

A pioneer who expanded education

The journey to finding the error began about four years ago when the family hired Butsch Freeland to research their lineage. Brother and sister Tom and Liz Shortridge and their cousins John Shortridge and Barbara Shortridge Cooper wanted to take the records and photos floating around family collections and gather them into a more complete history. Abraham's life, of course, would be a large part.

"We certainly knew Shortridge High School was named for him, but we really didn't know much and didn't hear much growing up about him," said Tom Shortridge, who is Abraham's great-great-grandson.

Abraham was born in New Lisbon and valued education early, even selling his horse to raise money to attend a school near Richmond, Butsch Freeland wrote in a history of his life that she shared with IndyStar. He went on to help found the Indiana State Teachers Association and teach at North Western Christian University — now known as Butler University.

Abraham became the first superintendent of Indianapolis Public Schools in 1863, advocated for Black students to attend and reopened Indianapolis High School — which would later be named after him, according to the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. He also helped start the Indianapolis Public Library.

Billy the Kid's time in Indianapolis: The outlaw became famous out west, but he had big Hoosier ties

Suffering from failing eyesight, Abraham gave up his superintendent position but was recruited to become the second president of Purdue University. Later in his 85 years of life, he sat for a portrait by renowned Hoosier artist T.C. Steele, owned a farm near Irvington and — in a major accident — lost his leg below the knee after an interurban car struck him.

"He has retained splendid courage and has borne it all with a patience that is nothing short of remarkable," the Indianapolis Star reported after the accident in 1906.

While Butsch Freeland did find a few newspaper articles that mixed in the name "Abram," more than 200 documents by her count — including city directories, the U.S. census, and mortgage and deed papers — showed that Abraham was indeed Abraham.

But not on his death certificate.

Correcting an error

Abraham's daughter-in-law Lillian Rebecca Martin had filled out the form, which included errors and gaps where she indicated that she didn't know information about his family. She was from near Logansport and hadn't been married for long, Butsch Freeland said.

"He died, and her husband — the son, Walter — was not well, and she was the second wife and just didn't know the family that well," Liz said.

With that information, the gravestone was ordered, and "Abram" has made its way into histories written since, Butsch Freeland wrote in her history of Abraham's life.

Growing up, Tom and Liz heard their great-great grandfather referred to as Abraham, A.C. and, sometimes, Abram. But now that they've seen overwhelming evidence pointing to his real name, a new gravestone would right a wrong, Tom said. And it could be fashioned to match the stone of Abraham's first wife, who is buried next to him.

"As an ancestor of ours and one who meant a lot to this city, in a way of education especially, we want that to be right so that anybody who ever sees that or anybody who decides to know more about it or whatever, that headstone will say 'Abraham C. Shortridge,' which is correct," Tom said.

Looking for things to do? Our newsletter has the best concerts, art, shows and more — and the stories behind them

Contact IndyStar reporter Domenica Bongiovanni at 317-444-7339 or d.bongiovanni@indystar.com. Follow her on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter: @domenicareports.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Shortridge historian and family seek fix for error on educator's grave