Fault lines at Texas-New Mexico border complicate earthquakes linked to waste water disposal

This article is part of Shaky Ground, a collaborative reporting project between the Carlsbad Current-Argus and KRWG Public Media.

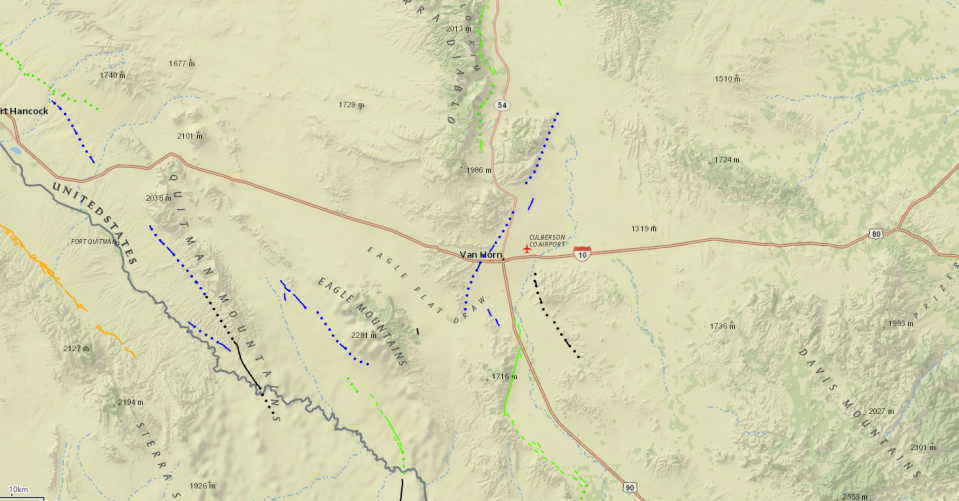

A group of fault lines sit underground near Van Horn, Texas, dating up to 1.6 million years old, according to a map published by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

While the fault lines might have been largely immobile for a millennia, today they are potentially responsible for the growing hazard of earthquakes throughout West Texas and southeast New Mexico.

The remote, far West Texas city is on the western edge of the Permian Basin – an oil and gas region known as the busiest in the U.S. But it’s also become known as the epicenter of an increasing number of earthquakes, as the industry’s operators continue injecting millions of gallons of wastewater every year back underground.

The water, known as produced water, comes to the surface with oil and gas – up to 10 barrels for every barrel of oil. More than 5 million barrels of oil are produced in the Permian daily as of June, according to the Energy Information Administration, meaning the region could produce up to 57 million barrels of wastewater.

In 2022, there were 2,404 earthquakes at M 2 or more in the Permian Basin spanning southeast New Mexico and West Texas, with 583 such events in the first quarter 2023, meaning the region was on pace for 2,332 seismic events by the end of the year.

This seismicity happened as production continued a steady rise to about 5.3 million bpd in 2022 and 5.7 million bpd as of May 2023.

When injected, typically directly back into the ancient rock formations 10,000 feet underground, the water pressurizes fault lines like those near Van Horn.

As the pressure builds around these faults, or cracks in underground rock, formations sitting in place for millions of years can start to move.

A report from the USGS likened the effect to an air hockey table. When the air, or pressure, is turned off the friction between the puck and surface of the table keeps the puck in place. As the air flow or pressure is increased, the puck can slide around the table.

On the Earth's surface, this movement creates the shaking effect felt by people, potentially hundreds of miles from the fault, that can damage property and risk human life.

The USGS reported the effect of waste water injection can be difficult to predict as the wells can induce seismicity 10 miles or more from the injection site.

Note to readers: Our newsroom hopes you find value in this article. Please consider becoming a financial supporter of local journalism. Subscribe to the Carlsbad Current-Argus.

Triggering an earthquake depends on the volume and rate of water injected, the presence of faults and the presence of pathways for the fluid to flow from injection into the fault.

"When you make large changes to the state of stress in the subsurface, you can cause earthquakes to occur," said Mairi Litherland, manager of the Seismic Observatory at New Mexico Tech. "You know, based on what we've seen elsewhere, we can be very confident that that rise in seismicity is attributable to the fluid injection that's going on, you know, throughout the region."

Seismic data can be used to better inform the planning of injection wells in New Mexico, Litherland said, spacing the wells out better to avoid stimulating underground rocks into movement.

"Certainly when it comes to the seismicity issue, not every injection well is created equal," she said. "There are some places where fluid has been injected into the subsurface and it doesn't cause seismicity."

Adrian Hedden can be reached at 575-628-5516, achedden@currentargus.com or @AdrianHedden on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Carlsbad Current-Argus: Fault lines at Texas-New Mexico border complicate earthquakes