FDA struggles to remain independent amid race for virus cure

Peter Marks was a natural fit for a new White House project tasked with developing a coronavirus vaccine. The cancer specialist spent nearly a decade at the Food and Drug Administration, most recently overseeing the office that approves vaccines and gene therapies.

But Marks quit last month just days after joining President Donald Trump's Operation Warp Speed, a venture partnering government with private companies in the vaccine race. He returned to his old FDA job full time after a clash with White House coronavirus coordinator Deborah Birx about how the government was prioritizing potential vaccines during a tense meeting of the White House coronavirus task force, according to three people familiar with the event.

Marks quickly realized he'd be more useful running the FDA office with ultimate authority over vaccine decisions than being part of a political team, two of those people and a current health official said. A memo to FDA staff said Marks was returning because the White House had assembled enough other experts to do the job.

"That was nonsense," said the current administration official, who is familiar with Marks' thinking. "He actually quit in disgust."

Marks's abrupt switch was the latest sign of the FDA's struggle to fend off outside political pressure, particularly from the White House, amid the desperate search for a coronavirus cure. The agency rushed to greenlight the unproven coronavirus treatment hydroxychloroquine for wide use after President Donald Trump touted the drug. At the behest of the White House, FDA officials met with wealthy Trump donor Larry Ellison almost daily to discuss a hydroxychloroquine tracking project. The White House also has pushed the agency to authorize other treatments, like the Japanese flu drug Avigan, despite limited evidence the drug could treat Covid-19 and concerns it causes birth defects.

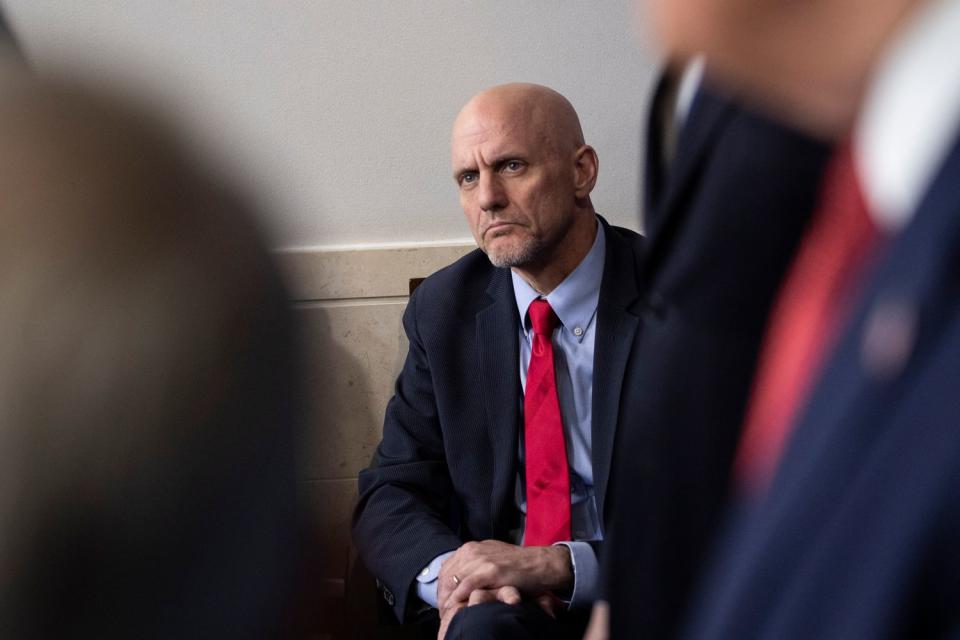

The unprecedented effort by the White House to intercede at an agency that's supposed to make independent judgments based on medical science is raising alarms among health experts inside and outside the administration. POLITICO spoke with six current or former senior HHS officials and three other people familiar with the White House coronavirus response. Several expressed concerns that FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, confirmed to his role just a month before the coronavirus reached the U.S., has not been a strong enough voice for an agency charged with regulating drugs and vaccines. Some acknowledged friction between FDA officials and White House and coronavirus task force members.

Those factors could complicate crucial choices the FDA will make in coming months about which drugs or shots reach the public. The first coronavirus vaccines are hurtling into late-stage clinical trials, aiming for emergency use by year's end, and efficacy results on drugs are flooding in. And the delicate balancing act by Hahn, Marks and other agency leaders caught between medical science and pressure from the White House has already hampered the FDA's efforts to help increase the country's testing capacity, the current and former health officials said.

In a statement, Hahn denied that political pressure had influenced his agency's coronavirus response. "The FDA has remained an unwavering, science-based voice helping to guide the all-of-government response," he said to POLITICO. "I have never felt any pressure to make decisions, other than the urgency of the situation around COVID-19."

But others say some of the agency’s highest-profile decisions regarding the pandemic, such as its stumbles on testing, are difficult to understand. "It's hard from the outside to figure out why some of the things that are happening are happening," said Alberto Gutierrez, FDA's former diagnostic chief and a partner with the health consultancy NDA Partners.

The hydroxychloroquine scramble

The pressure started early on — and it involved one of the president's wealthiest backers.

During the first weeks of the pandemic, when the FDA was struggling to approve coronavirus tests, agency officials got an unusual request. The White House wanted them to talk to Oracle CEO and top Trump donor Larry Ellison about an application the company was building to track hydroxychloroquine use outside of clinical trials, which it wanted to donate to the government. The request came as the president began championing the unproven coronavirus treatment on the press briefing stage.

Agency leaders scrambled to meet with the wealthy Trump ally and his team, in what turned into near-daily talks, according to three HHS officials. The FDA's top drug regulator, Janet Woodcock, eventually raised strong concerns about the Oracle proposal, saying it would promote off-label prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine without proof the drug was safe or effective for coronavirus patients. But the damage had already been done. The Oracle meeting had sucked in multiple senior staff, siphoning resources away from other potential therapies or rising issues for FDA, two current senior health officials said.

Oracle donated its application to the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA's parent agency, on April 20. But the FDA — the HHS branch charged with tracking drug safety and efficacy — does not have access to it. Three current health officials told POLITICO they are not sure which government employees, if any, are using the Oracle database.

The White House did not respond to requests for comment on the matter. Oracle executive vice president Kenneth Glueck said that while Ellison's talk with Trump led the White House to instruct health officials to work with the tech company, the project morphed into an application to track the use of all Covid-19 therapies, not just hydroxychloroquine.

Patients must opt in to share their data, which doctors can theoretically use to make better prescribing decisions. But it’s not clear how useful the Oracle approach is. There are already multiple FDA databases that track drug safety, and regulators and doctors typically look to clinical trial data for information about a drug’s effectiveness.

An HHS spokesperson said that the department focused for the first month on "data collection and data security" and will begin analysis of the Oracle database when there is enough information to add value. The project now includes information from more than 30,000 people who have taken hydroxychloroquine or other drugs, the spokesperson said.

The FDA has had to walk back some of the quick decisions it has made under pressure from the White House. Though career FDA staff advocated clinical trials for hydroxychloroquine that could take months to produce results, the agency authorized it for widespread use on March 30. Then it issued a warning on April 24 specifying that the drug should only be used under close medical supervision because of potentially fatal side effects.

The FDA also allowed more than 150 faulty antibody tests to be distributed without independently verifying their efficacy, and then told companies they'd need to have the products reviewed or pull them from the market after it became clear many didn't work.

Baptism by fire

When Hahn, a cancer doctor by training, took office in December, the hottest issue facing the FDA was e-cigarettes. But within weeks, the coronavirus reached the United States, thrusting him into a starring role in the government’s pandemic response — despite his lack of prior experience in public health, infectious diseases or government.

The FDA began working around the clock to evaluate potential coronavirus tests, treatments and vaccines, even as the president promoted unproven drugs from the White House podium and promised a shot within the year.

Some of the current and former officials who spoke to POLITICO said they were troubled that Hahn hasn't pushed back more forcefully on outside influences. His relative inexperience has exacerbated worries within the agency about whether it can remain independent of White House pressure to fast-track experimental coronavirus vaccines or quell lingering questions about the reliability of antibody testing, said three current and former health officials.

"I don't know where his voice is in this," a former HHS official said.

So far, Hahn “has not put his foot down on any issue," said a current official. "Maybe some of that is the politicization, maybe some of that is that he did not have his opportunity to get sea legs at the agency before Covid began. But this is a do or die moment for the agency now."

HHS secretary Alex Azar backed up his FDA chief. "Dr. Hahn has been a strong and effective leader of the Food and Drug Administration from his first day on the job and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic," Azar said. "The agency has been instrumental in making PPE, therapeutics, diagnostics, and eventually vaccines available for the American public as quickly as possible."

Surgeon General Jerome Adams also praised Hahn's handling of the pandemic. "I think he was really pressured by the epidemic itself to try and decrease regulatory barriers," Adams said. "He’s really done a good job of always saying 'We’re doing this in an emergency situation and we’re also going to make sure we’re following the data, so we can quickly react to and respond to any problems.'"

The FDA chief's reticence was clear at the April 28 meeting of the White House coronavirus task force where Birx laid into Marks about the nation’s vaccine strategy, according to the three people familiar with the event. Birx pressed Marks for clearer answers on which vaccines the government was working on or funding, and why it was not funding or studying others, said a fourth official familiar with the meeting.

But the FDA's vaccine chief does not make those calls. Other scientists, including the chief of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, dictate key funding decisions; BARDA's former chief Rick Bright had been ousted just days before the tense task force meeting — a move Bright alleged was due to his resistance to hydroxychloroquine.

Neither Azar nor Hahn spoke up for Marks in the meeting, according to the three sources, who along with two others in that meeting said that Birx and Marks have since patched up the misunderstanding. The fourth official, and a fifth in the room, characterized the Birx and Marks exchange as brief. But the tense atmosphere — and silence from both Hahn and Azar — struck several attendees and people briefed afterward.

Birx referred questions on the matter to a task force spokesperson who declined to comment.

Asked about his departure from Warp Speed and the task force, Marks released a statement through the FDA press office. "I believe that the American public will be best served by my return full time to FDA, where I can continue to work collaboratively, with industry, government partners and other researchers and provide regulatory advice to expedite the development and availability of vaccines to combat COVID-19," he said.

Marks's decision to leave Warp Speed came just a week after President Trump named Moncef Slaoui — the former head of vaccines at GlaxoSmithKline and until recently, a member of Moderna Therapeutics' board of directors — to lead the program.

Hahn, Marks and other FDA leaders will soon need to make critical decisions about the coronavirus response, like authorizing the first vaccine. Moderna is readying its government-backed vaccine candidate for phase II safety trials and a swift move into final phase III studies of safety and efficacy, aiming for approval this year. And several other companies are hot on its heels.

"You just know that they are just under enormous pressure. But look what happened to Rick [Bright]. Look what happens to anyone else who has resisted pressure," said one former health official.

The current and former government health officials POLITICO spoke to saw Marks' decision to leave Operation Warp Speed as crucial to shield FDA decisions on coronavirus vaccines from political pressure. Although President Trump has repeatedly promised that a vaccine will be available by the end of the year, it is Marks who will be the ultimate arbiter. In his current job, he will oversee FDA review — and any eventual approvals — of vaccines.

"If a one-year timeframe is to be made possible, Dr. Marks' intellect and credibility will be needed to guide the FDA approval of a safe and effective vaccine that will be given to hundreds of millions of people who are not ill," said Steven Grossman, president of health policy and consulting firm HPS Group.

Marks' move was welcomed by another current senior HHS official. "It has been very clear to me that he is needed" back at the FDA, the person said. "And getting the regulatory piece right is going to be a critical part of getting to a viable vaccine."