On this day, Supreme Court invalidates key FDR program

On May 27, 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down an important part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s NRA plan, symbolized by an iconic Blue Eagle logo.

The court decision invalidated a key part of the National Industrial Recovery Act, or NIRA, one of the projects passed during FDR’s 100-day program in 1933.

The NIRA has two key components: an industrial recovery program that included a wave of regulations seeking to foster “fair competition,” and a huge public works program.

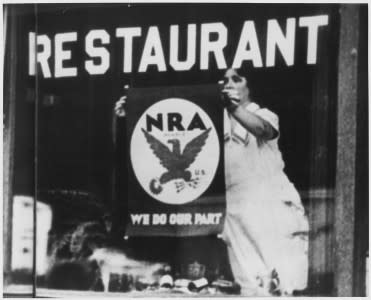

The National Recovery Agency, or NRA, was created to implement the Recovery Act, and it established a series of codes and rules for businesses as part of the “fair competition” experiment. The administration asked businesses to display the Blue Eagle logo, an emblem signifying NRA participation, as a act of patriotism.

But to many people, the program was more like an albatross. The NIRA and NRA weren’t expected to be renewed by Congress, which received many complaints about the excessively detailed program.

One problem was that the NIRA didn’t have widespread support in the Senate, even though it passed the NIRA as part of a recovery effort during the Great Depression. (Among the act’s critics in the Senate was Hugo Black, who Roosevelt would nominate to the Supreme Court two years later.)

The overly ambitious NIRA had something to anger most business and societal interests. It allowed for the suspension of anti-trust laws and forced certain industries to align. Its fair-competition codes allowed for price and wage fixing. The NIRA also called for industries to regulate themselves even as it required those industries to agree to follow many codes which were to be vetted at public hearings.

And even though NIRA encouraged the unionization of workers to seek better conditions, the efforts to form unions became disorganized.

The NRA as an agency had the power to push for voluntary agreements about work conditions and fixed prices, drawing up more than 500 fair practice codes for industries.

In 1934, one of these codes established competitive rules for the live poultry industry in New York City. The Schechter brothers faced 60 charges of violating the “Live Poultry Code,” including offering unfit chickens for sale and not offering a minimum wage to workers. The brothers were found guilty on 20 counts in what became known as the “Sick Chicken” case.

The brothers lost one appeal but pursued the case to the Supreme Court, where the Justices ruled in favor of the Schechters and invalidated the part of the NIRA that allowed the executive branch to establish codes to regulate industries.

Writing for a unanimous court in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes said the legal action against the Schechters violated the Constitution’s Commerce Clause because the chicken business was contained within New York State. And more importantly, the Court said Congress gave the Roosevelt administration too much power to control the economy through the use of the fair practice codes.

Within a week, President Roosevelt criticized the justices at a press conference, starting a very public feud with the Court that lasted for several years.

“You see the implications of the decision. That is why I say it is one of the most important decisions ever rendered in this country,” Roosevelt told reporters on May 31, 1935. “We have been relegated to the horse-and-buggy definition of interstate commerce.”

After the fights between Roosevelt and the Court simmered down, key labor protections that came out of the NIRA survived as laws passed later in the decade, including the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Constitution Daily History Stories About The Founders

Forgotten facts about George Washington’s private life