Fear, racism, misogyny: Legacy of Staunton’s tumultuous 1979 echoed long after crime spree ended

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Summer, 2021. A few days a week, you can find a Black man in his mid-sixties named Ted working at White’s Travel Center in Raphine, a sprawling complex for truckers and travelers off Interstate 81, that strip of highway stretching from New York’s Canadian border through half a dozen states to Knoxville, Tennessee.

He’s semi-retired after decades of work in hospitals in Richmond and Harrisonburg.

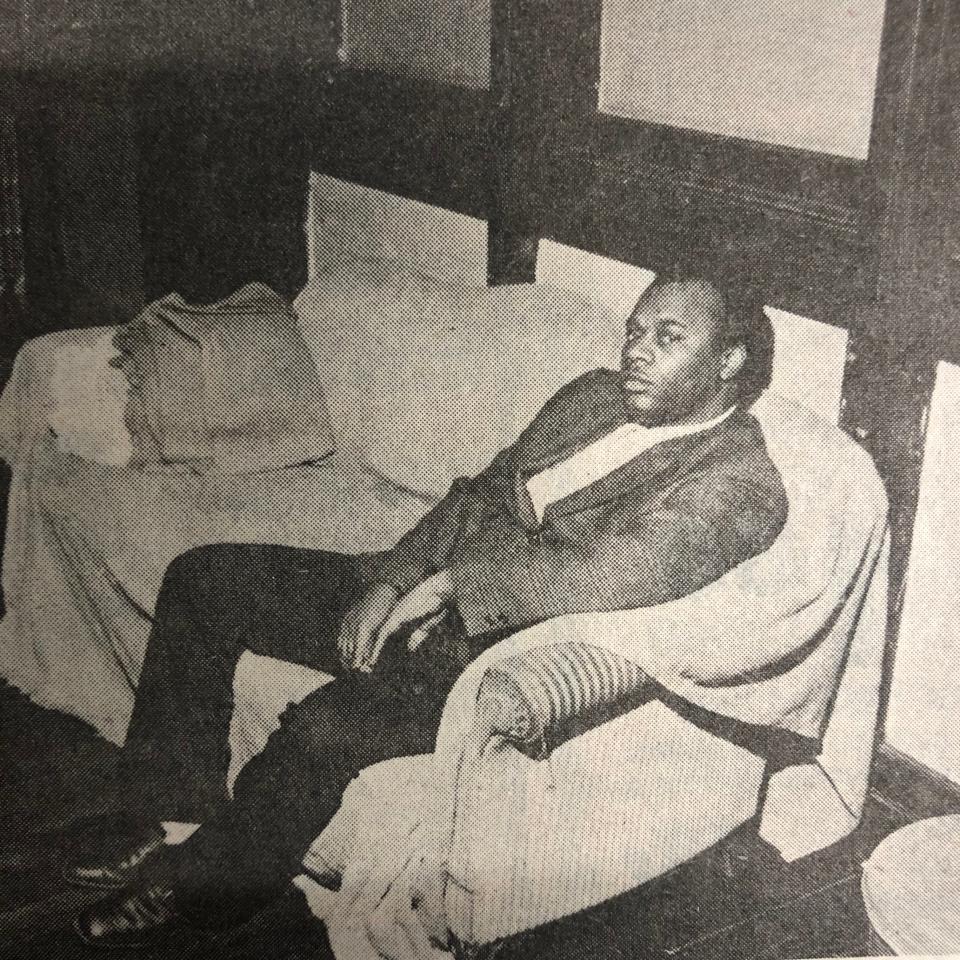

If James Bruce Robinson hadn’t been caught peeping in a window by a kid playing spy, it’s likely Ted Gray would have spent a few of those decades in prison for a rape he didn’t commit, after being falsely identified by the victim.

While much of his life has been spent in areas close to Staunton, he never came back to settle in the city that cost him his job and some friendships in 1979, when he was arrested with great fanfare in mid-September. Many women in the community, believing the worst was over and that a months-long crime spree had finally come to an end, relaxed their guard.

Two weeks after Gray’s arrest, the stocking mask rapist broke into a home and raped another Staunton woman.

Gray was already in jail, and remained incarcerated even after that attack. His rape charge was certified before a grand jury in mid-October as the Staunton police were requesting help from the Virginia State Police to find the real rapist.

Gray himself was dumbfounded when he was arrested. “I went to school with her,” Gray said of his accuser. “Why would she pick me?”

*

In 1982, the Staunton Leader covered the issue of rape again. This time it was an in-depth series by female reporters on the difficulties of securing convictions of accused rapists. Those stories included an analysis of the complexity of catching and prosecuting rapists, and the problems with laws that were meant to protect victims.

Gone were the headlines suggesting that if women just had “common sense tips” to protect themselves, they might not be attracting rapists to their doorstep.

Georgina Hickey, the chair of the Department of Social Sciences and a professor of history at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, has heard that before. Hickey’s family had moved to Virginia Beach in 1978. She doesn’t remember hearing about the serial rapist in Staunton, but recalls how late ’70s and early ’80s culture seemed to amplify the idea of urban areas as dangerous for women.

As a girl and young teenager “I was absolutely conditioned to be afraid of what was lurking out there,” she wrote. The professor has been tracing the history of how public space has been defined across the 20th century in American cities for her book “Breaking the Code: Challenging Gender Segregation in the Twentieth Century Urban United States,” to be published in 2023.

“Once something gets labeled ‘common sense,’ of course, there is very little room to push back against it. It absolves the larger community of responsibility while holding individual women responsible for whatever violence they might encounter,” she wrote in an email to The News Leader.

Hickey said that the multiple arrests of Black men helped convey a message that the streets were safe only for white men.

“This case seems to have quickly triggered longstanding racial tensions, creating fear and suspicion on both sides. And, of course, false accusations of Black men are no surprise in this atmosphere. It foreshadows what will happen a decade later in the Central Park Jogger case.”

It might stretch someone’s memory to call up any instance in Staunton where, in the midst of serial crimes, two white men were held for individual incidents while the local police publicly sought help to find the real culprit.

It took Special Agent Stilwell to bring all the cases together into an organized investigation, and to tell the chief of police what should have been obvious — that they had two innocent Black men incarcerated, and one very active rapist still at large.

As the fall of 1979 stretched toward winter, Stilwell’s task force, aided by the React citizen’s group, regularly noted the appearance of any lone Black male in his 20s on the streets of Staunton and often asked the men to identify themselves and explain what they were doing out at night.

The law enforcement strategy is seen today as racial profiling and targeting. It still happens, though.

“There is a long history, of course, of controlling and persecuting Black men in the name of protecting white women,” wrote Hickey. “The narrative is controlling on both sides — perpetuating images of Black men as violent, needing to be surveilled and controlled, and women needing to be ‘protected,’ which often translated as advice to stay home.”

*

Noreen Renier wouldn’t find out about the arrest of Robinson until early 1980, when she’d read about it in the newspaper like everyone else.

It’s something that both bothered her and comforted her over the decades. She wasn’t a police officer or detective. She didn’t face the pressures those professionals faced.

“I don’t solve crimes,” she said in many interviews over the years. “The police solve crimes.”

An invitation to speak at the Peninsula Tidewater Academy of Criminal Justice in Hampton, Virginia in the early 1980s put Renier in front of a roomful of cops, speaking between a parapsychologist and an FBI agent. There she met Robert Ressler, one of the FBI agents who founded the Behavioral Science Unit and coined the term “serial killer.”

Ressler was impressed by her demonstration of psychometry; she had successfully described all but one of the police officers who’d put a ring or watch in an envelope with only their initials to identify them.

After her talk, Ressler determined that her one failure was due to an officer using the watch of a colleague in his envelope. That man sheepishly apologized to Renier, and she was invited to speak to FBI agents at Quantico.

There, among the brain trust of the investigative world, she would be the first and only psychic to lecture the FBI on her methods. Again, she won over the tough crowd. Later, she recalled in her autobiography “A Mind for Murder,” she was escorted to an agents-only lounge inside the building called the “Board Room.”

Loosened up by a few drinks, the agents began approaching her one by one, dropping a watch or ring on the bar in front of her and asking, “Can you tell me something about myself?”

Maybe these guys weren’t so different from her typical clientele after all, she thought.

*

If you were to walk around downtown Staunton and note all the buildings related to the spree of the stocking mask rapist, you’d start to get claustrophobic. You can’t live downtown without being able to walk to one or more of them in a matter of minutes. Without being aware of it, I lived for five years in a house next door to where one of the attempted rapes took place.

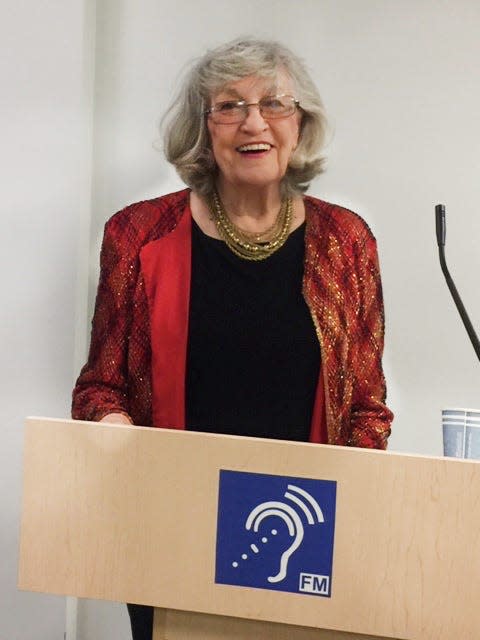

One house that might stand out as the last place to visit on such a stroll would be an old building on Church Street where Audrey “Sugar” Higgs hosted and exhorted a group of Staunton’s women to demand accountability from their city and police.

Nearby, one of the oldest churches in the city raises its spires to the sky, and tourists walk its grounds and stand among its pews every week to get a glimpse of the Tiffany stained-glass windows. Staunton is still pious enough that the top of every hour is a brief competition between multiple sets of church bells.

Meanwhile the house on Church Street silently stands as the beginning of a new covenant among women to claim their lives in a modern era.

A few years after the stocking mask rapist was imprisoned, Sugar told Charles Culbertson, who was still living under her roof, “Charlie, I want you to write my obituary.”

She was dying, and couldn’t bear the thought of boring the populace in the aftermath of her last breath with a run-of-the-mill obit. Not many people called him “Charlie” and got away with it, but Sugar did.

It took Culbertson nearly a decade to finish that obituary, but eventually, when he could command a spot on the Opinions page of The News Leader, he wrote an elegy to his long-lost landlord and friend.

*

One element of the case with a long American history — that of Black men confessing to crimes they didn’t commit — is not lost on history professor and Dean of the Mary Baldwin College for Women Amy Tillerson-Brown.

“I think of the thousands of men who have been coerced.”

Tillerson-Brown sat for an interview in Staunton at a coffeehouse directly across the street from the apartment building where James Bruce Robinson lived.

“Plea deals are usually made to shut the story up,” the history professor and dean said in October 2021.

She wondered if Robinson had appealed his conviction on the grounds his confession was coerced — he had — and wondered if the Staunton Police Department had done any DNA testing on the evidence to confirm the rapes were linked to a single rapist, and that the rapist was indeed James Bruce Robinson.

While an effort was made in recent years by the Virginia State Crime Commission to use DNA testing on evidence from over 800 convictions from 1973 to 1988, the case of James Bruce Robinson's conviction for the stocking mask rapist cases was not part of the Post-Conviction DNA Testing Program and Notification Project, according to Katya Herndon, the chief deputy director of the Department of Forensic Science.

It may be that there is no evidence left to test.

The News Leader reached out to the Staunton police to request they test the PERK kit evidence in the stocking mask rapist cases, if any still exists. There has been no response.

*

The Ted Gray who spoke in an October 2021 interview is not bitter toward his accuser. “It wasn’t so much her,” he said. He said a retired judge told him later that “he felt she was coached into saying it was me.”

The state’s General Assembly gave Gray $5,000 months after he was released to make up for the loss of his livelihood while in jail. In those months he’d lost more than a livelihood; he’d lost friendships and the trust of others.

As a Black man he'd also lost any remaining trust in police.

“It’s more systematic now than it was back then,” Gray said of the racism in the police today. “But to me it’s still the same. In my own personal way, you know, you can’t even trust them.”

He’d already talked to the police on more than one occasion. Detectives Whisman and King had approached him to ask informally if he knew anything about the rapes. He was on a list of nearly 20 potential suspects the task force checked out after Special Agent Stilwell arrived. They treated him with respect, he said. “To me, they were all right.”

Gray felt there was pressure coming from other people to bring someone in and say they were the stocking mask rapist. “That’s what they built me up to be.”

He was a newly free man, and just starting to feel the social constrictions of this new freedom, when he read in the paper about Robinson’s 20-year plea deal, famously calling it “the deal of the century.” It’s the same deal they were offering him to confess for a single rape, Gray said.

*

The first man arrested in the stocking mask rapes, Gordon Smith, died in 2019. He lived for years on Kalorama Street, across the road from several of the houses broken into by the stocking mask rapist, and a few steps from where James Bruce Robinson was arrested in December of 1979.

James Bruce Robinson was released in 1995, at the age of 38, after serving 15 years in prison.

— Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a regional storytelling and watchdog coach in USA TODAY Network-Southeast. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

PART 1: Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

PART 3: Cops admit predator is at large. Staunton women told to use ‘can of hair spray’ for defense.

PART 4: ‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

PART 6: ‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

PART 7: Women make demands. A psychic makes predictions. And a Virginia city holds its breath.

PART 8: Things go ‘round and round’: Two unlikely sources help police close in on Staunton predator

PART 9: After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: 1979 Stocking Mask Rapist case left Staunton with a troubling legacy