'They are fearing people.' Downtown's homeless, panhandlers not a safety threat

This is part of The Enquirer's Future of Downtown series and part three of a three-part series on crime and safety. Check out our past coverage on violent crime Downtown and auto-related crime.

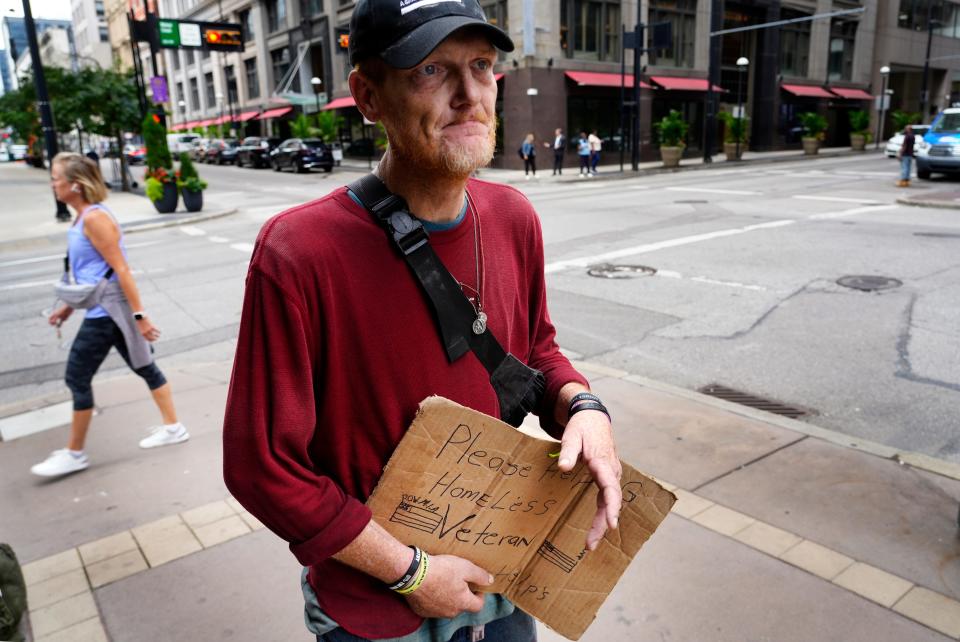

You may have passed Angel sitting on Sixth Street Downtown. Her sign reads, "Homeless Please Anything Helps." She may have said "hi" when you walked past but didn't ask for money.

Angel is quiet, 34, and living in a tent.

One thing she is not is dangerous.

Data shows that despite the fears Enquirer readers expressed in several surveys, the panhandlers and homeless people encountered Downtown are, like Angel, no threat. In fact, they are more likely to be the victims of crime.

"In my 25 years working in this field, I'm unaware of a single incident where a person who was homeless attacked a person downtown," said Kevin Finn, president and CEO of Cincinnati-based Strategies to End Homelessness. "But I'm aware of many instances where non-homeless people attacked homeless people."

Statistics show that the chronically homeless − those who don't usually take advantage of the nearby shelters − aren't at the root of much crime in downtown Cincinnati despite the perception that they are. Cincinnati police records reveal that the reported violent crimes committed by actual homeless people against Downtown residents and visitors are non-existent.

For her part, Angel is working with Cincinnati Center City Development Corp., also known as 3CDC, to find lodgings and a job.

Downtown's unhoused population are the ones at risk

Those who are homeless are more likely to be victims of violent crime than perpetrators, research shows, with the exception of homeless encampments where crime is more common.

A Los Angeles County Department of Public Health study found that homeless people were 14 times more likely to be murdered, while University of California San Francisco researchers reported that people who slept on the streets had rates of death 3.5-times higher than those who slept in shelters.

Across the country, a small percentage of the unhoused sleep on the streets compared to in shelters. Two-thirds of the homeless experience mental health issues or substance abuse, according to the National Healthcare for the Homeless Council.

That’s largely the case in downtown Cincinnati, Finn said. While the majority of the city’s homeless population includes families or people under the age of 35, the folks on the streets skew older and male, and “tend to be the people with much, much higher rates of severe substance abuse problems and severe, untreated mental illness," he added.

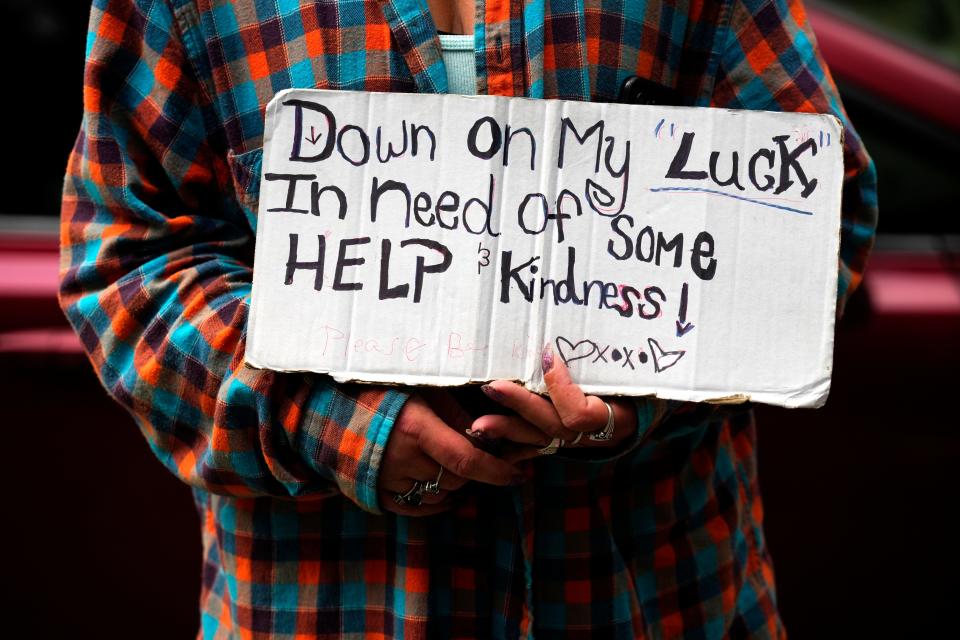

‘Panhandling is not what homelessness looks like’

Outreach workers from Strategies to End Homeless keep tabs on Downtown panhandlers. According to their records, about two-thirds of people panhandling on Cincinnati's streets said that they do actually have places to stay.

"[Panhandling is] not what homelessness looks like. It could not be more inaccurate," Finn said. "The average person experiencing homelessness has never panhandled and would be just as embarrassed to do so as you or I would be.”

That doesn’t mean some don’t do it. They just represent a smaller portion of the total panhandlers downtown. Vocal, aggressive panhandling is often a sign of severe, untreated mental health or substance abuse problems.

Panhandling is legal in Cincinnati, as long as it isn't aggressive, which includes verbally requesting money, intimidating someone with abusive language, touching them or following them. It's also illegal to solicit near a bank, ATM, bus stop, parking meter or a crosswalk, according to the city's municipal code.

Citywide, Cincinnati police charged people with aggressive panhandling five times in 2023, as of November, city data showed. Police spokesman Lt. Jonathan Cunningham said the department understands how people experiencing homelessness might make Downtown visitors feel unsafe.

"However, a person's lack of permanent housing is not an immediate indicator of criminal activity," he said in a statement. "The safety of our citizens, regardless of housing status, is the top priority for our department."

Jackie Bryson, president of the Downtown Residents’ Council, discourages her Downtown neighbors from giving money in either case. Her tips for responding to a panhandler: politely say "no," give away food, donate to the causes that take care of this issue, or call 3CDC's ambassador hotline for immediate assistance. Just treat them with decency, she said.

"Most of these people are so docile," Bryson added. "They might make eye contact with you but they won't say anything. It's important to draw the difference between a normal panhandler and someone who clearly has mental health issues and aberrant behavior.”

Solutions to curb the homelessness crisis

A number of groups are helping the unhoused and panhandlers in downtown Cincinnati. Through organizations like GeneroCity 513, an initiative of 3CDC, people have access to regular medical care, showers, cell phones, food and job services.

“Homelessness is a visible issue with invisible solutions,” said Laura Allen, case manager supervisor.

As of July (the most recent figures available), six full-time GeneroCity outreach workers, all hired through the Greater Cincinnati Behavioral Health Services, act as case managers for 68 people currently experiencing homelessness in Downtown and Over-the-Rhine, and 17 people who panhandle but may have homes. Outfitted in purple shirts, the case workers conduct daily check-ins with their clients and rely on an application called Clarity, a homeless management information system, to keep track of their needs.

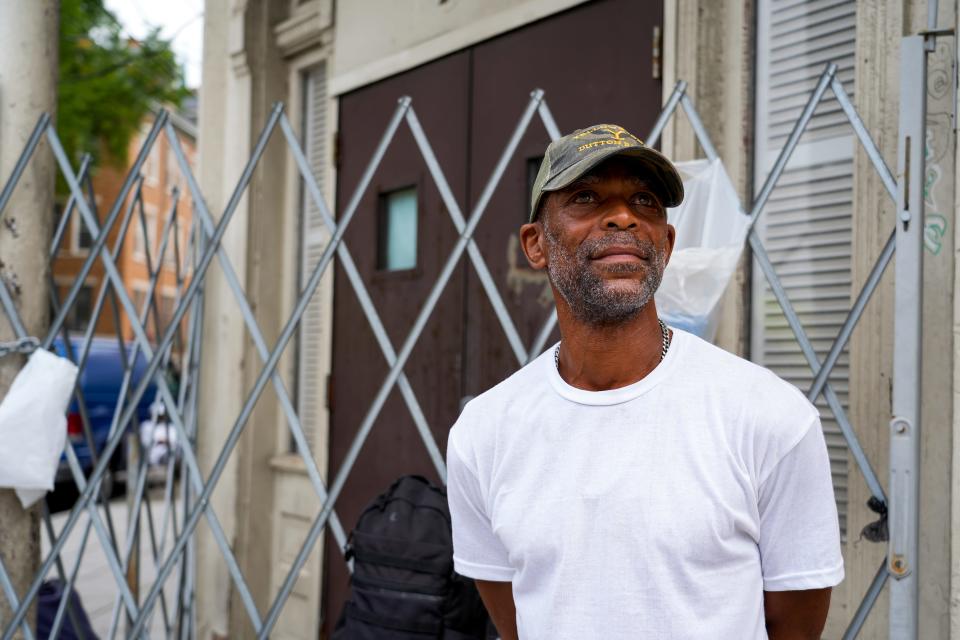

Jerome Mathis, 55, is a former Westwood resident and current GeneroCity client. He wants people to know that he isn’t helpless. “We are the opposite,” he said. “We want to be informed about our situations, we want help, but a lot of us don’t know how to ask for help.”

3CDC wants to build a new shelter in or around the central business district to support those people who are least likely to get off the streets on their own. They are currently looking for a partner organization to run the facility. So far, a location has not been decided.

To Steve Leeper, 3CDC's CEO and president, getting the most vulnerable off the streets will also benefit Downtown and help promote it as a safe, inviting neighborhood. "If we treat them properly and with dignity by giving them a place where they can get help, then another problem gets solved," he said.

‘They are scared themselves’

Dr. Tracey Skale, chief medical officer for Greater Cincinnati Behavioral Health Services, is arguably one of the more popular people among downtown Cincinnati’s homeless community. For three decades, she’s worked as the community doctor for the people you pass by on the city streets. She loves them, and they love her.

“There's a list of people who garner a lot of public awareness and most of them are mine. We’re partners,” she said. “I'm the doctor for anyone who is homeless and severely medically ill.”

Skale handles her own appointments, but also refers patients out to area specialists or primary care providers. She dually takes to the streets to de-escalate situations with her patients when necessary and to help them get what they need. “Sometimes they don’t know how to make their needs met without making a scene,” she added. “I figure out what’s wrong and it’s usually something small like trying to get a bus pass.”

But there are much more serious mental and physical ailments she helps them tackle: Hypothermia, high blood pressure and schizophrenia are common amongst this patient population. Victimization is also all too real.

“So many of my patients have had repeated head injuries from being kicked or pushed,” she said. “They are fearing people. They don’t feel good enough, not deserving enough.”

That’s why it’s her mission to treat them with kindness, respect and dignity while advising others to do the same. It takes a collaborative approach to get these people care, and eventually housing, Skale said.

“We can’t make our needs out to be their needs necessarily,” she admitted. “Not everybody really wants to be housed but we want people to be protected … just because they say no now, doesn’t mean they say no forever."

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Downtown Cincinnati: What about the homeless and panhandlers?