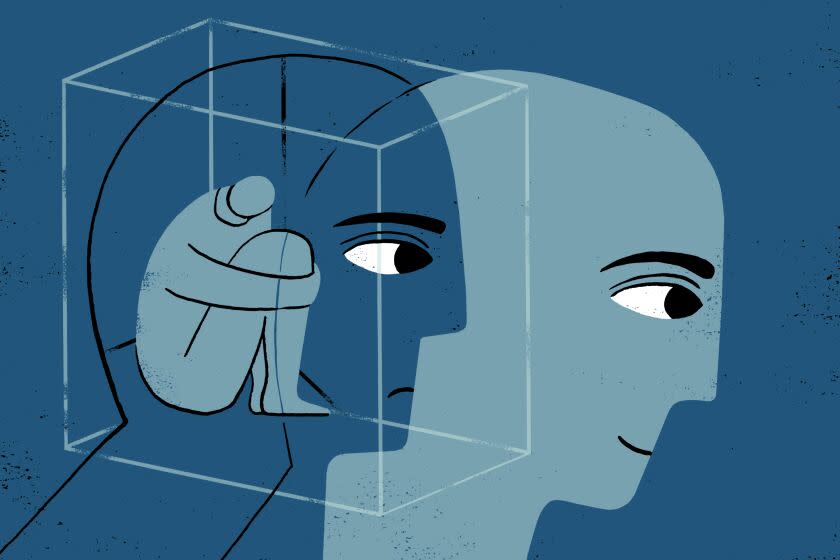

Bosses say they care about mental health — can workers trust them?

Faced with high levels of worker stress, anxiety and burnout as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many companies pledged that employee mental health would become a top priority.

Firms promised manager training to ensure bosses were more empathetic toward employee struggles. Some offered more mental health benefits, such as improved insurance coverage and employee assistance programs that offer free therapy sessions.

Despite the increased attention, however, the stigma of mental illness persists, preventing many with bipolar disorder, clinical depression and other maladies from feeling safe enough to be open with employers about their diagnoses and seek out workplace supports that they're legally allowed.

“The vast majority of the corporations, the businesses that are saying, ‘Oh, we care, mental health is important,’ I just don't believe it,” said Claudia Sahm, a 46-year-old former Federal Reserve economist who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2011 and advocates for healthy workplace environments. “Because until you actually put [in] the money and the resources and the training, it's just words."

Wendy Ascione-Juska is among the many workers who say they have learned that not all health conditions are treated equally in the workplace.

In her current job at the University of Michigan, when she experienced symptoms of mania or depression, she felt safe asking her boss for time off or to extend a deadline.

“The focus was on getting me healthy,” Ascione-Juska, 44, said.

That's in stark contrast to an earlier job in 2006, when she was newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder and experiencing a manic episode. She didn't know she had legal protections and could ask for help. Instead, her employer told her not to bring her "personal life" to work, she said, adding that she was soon fired.

“I needed to have a compassionate supervisor that could say, 'Alright, you're going through a difficult time. What can we do?'” she said.

Mood disorders are fairly common. An estimated 21.4% of adults in the U.S. have experienced depression, bipolar disorder or other similar conditions, according to a Harvard Medical School survey.

But frequency hasn't translated into acceptance in the workplace, and finding sustainable employment can be challenging for those with mood disorders and other serious mental illnesses. Of the 14.2 million adults with serious mental illness in the U.S., about 1 million are unemployed, according to a 2020 survey conducted by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — a 7% unemployment rate, which is significantly higher than the national average.

Those who have found work are often paid less. People with serious mental illness make an estimated $16,000 less per year than those without a serious mental illness. More research is needed, however, to understand whether discrimination is at play, and whether individual employment programs could help, according to a widely cited 2008 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

"These are conditions, just like other serious health conditions like diabetes or cancer, in which when people get effective treatment, when they're identified early with these conditions and receive treatment early, they can live fairly normal lives, just like anyone does living with a health or mental health condition," said Darcy Gruttadaro, chief innovation officer at the nonprofit National Alliance on Mental Illness.

In some cases, a person might show signs of bipolar disorder that are sometimes missed in a fast-paced work environment. That was the case for Natasha Bowman, a lawyer, published author and sought-after human resources speaker.

When the pandemic initially restricted travel and her work, Bowman found herself having unusual thoughts. As her hectic work schedule slowed, she wanted to run away from her family and eventually found herself in "a very, very dark place."

Her therapist couldn't identify what was happening and attributed the symptoms to the stress of the pandemic. In 2021, Bowman attempted suicide. She was involuntarily hospitalized and diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

As she learned more about her condition, her working style made more sense. She used to work for hours without sleep, all the while remaining highly creative and productive.

"I felt for some reason I had some sort of superpowers, but I knew that it wasn't usual for people to work at the capacity that I did," Bowman, 44, said. "I realized that I pretty much operated in a bipolar manic state for most of the time."

Bowman now takes medication to treat her bipolar disorder and said her diagnosis led her to start a nonprofit focused on workplace equity and mental wellness.

Many people with mood disorders don't feel they can be that open.

Some still fear the stigma associated with mental health conditions. A 2015 Rand Corp. study found that 69% of survey respondents said they would "definitely or probably" hide a mental health problem from their co-workers or classmates.

"The lack of safety or comfort with disclosure raises concerns about the degree to which individuals are able to obtain sufficient support in school or in the workplace," the study said.

Making a workplace safe for people with mood disorders starts with a company ensuring its managers and HR professionals are trained on how to help employees and connect them with support.

Experts said managers should avoid asking employees directly about their diagnoses — or playing armchair psychologist in an attempt to guess what diagnosis an employee has — and should keep the discussions to performance.

Managers should also create an environment of compassion where they can offer support.

”The workplace is probably the greatest opportunity to enact change because so many of us between the ages of 20 and 65 or 70 years old, we go to work," Rich Mattingly, founder of the Luv U Project, which advocates for mental health, said during a recent National Press Foundation panel on the topic.

"We spend our waking hours in the workplace. And what we could do at work, if we paid attention, would not only improve the workplace, but it would also improve home lives.”

Supporting employees with mood disorders goes beyond just a moral obligation and improved productivity. Employers can be on the hook legally if they are found to have violated federal or state disability protection laws.

“I've definitely noticed, personally, an uptick in the number of questions that I'm getting about mental health,” said Aaron Konapsky, senior attorney with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

He cited lawsuits filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2022 alleging that employers violated the rights of workers with psychiatric disabilities. In one case, a management company in Georgia settled for $250,000 over the termination of an employee with severe depression. After taking medical leave per their doctor’s recommendation, the plaintiff tried to return to work only to be told by the chief executive that they couldn’t be trusted to do their duties.

In 2008, Congress redefined the term “disability” under the Americans With Disabilities Act to include major life events that can impair any aspect of a person's life. Mental disabilities, when disclosed to an employer, are protected from discrimination.

Employers "aren't entitled to your whole medical file or notes about your therapy sessions,” Konapsky said, recognizing that employees may fear how their bosses could misuse information about mental health. But not disclosing could mean not getting the help a person needs.

Under the law, employers are obligated to provide reasonable accommodations that allow a worker to perform essential functions of the job so long as doing so doesn’t create an “undue burden” for the employer. For people with mood disorders, these can include quiet work environments, altered breaks and work schedules or changes in supervisor interactions.

Employers need to provide the same compassion for mood disorders that they provide for other serious illnesses, said Sahm, the economist.

“You wouldn’t fire someone who had cancer because they were grumpy, and every day wasn't a good day," Sahm said. "But with mental health, it's a lot harder for someone to recognize and give that same kind of understanding.”

Sahm has been open about her bipolar disorder for years, largely to try to reduce the condition's stigma and to help others feel like they weren't alone.

”Too many employers just kick you to the curb," she said. "People with mental health conditions are not worthless, they’re just sick. And they can get better.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.