A feast for the eyes: The Japanese art of fake food

Look, but don’t eat.

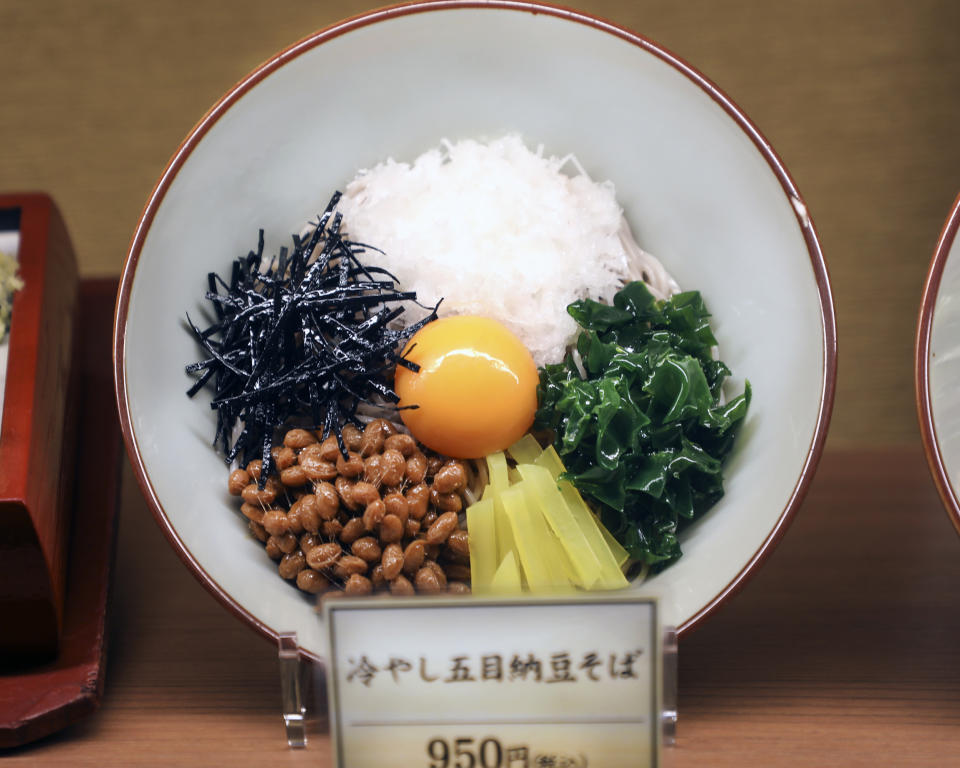

That’s the best way to consume the bountiful displays the likes of nigiri, curry and tempura displayed in the windows and at tables of so many casual dining Japanese restaurants. Known in Japan as "shokuhin sampuru" (食品サンプル), food models are often made of plastic or wax and emulate the look, texture and form of meals. They were first used by restaurants in the days before color photography as a way to show consumers what items were available on hand.

Today, their function has evolved into more of an art form. In the streets of Japan and those belonging to diasporic communities outside of the country, you’ll find sampuru beckoning potential diners inside eateries and shops. The fake and glistening delights also serve as travel keepsakes as well as ephemera of time gone by.

Like the best of food-related inventions, many have laid claim to being the original masterminds of food models.

In an interview with TODAY Food, Samuel H. Yamashita, a professor of History at Pomona College with expertise in Japanese and Pacific Rim cuisines, said the culinary history of sampuru has three different origin theories.

“One theory is that they originated in Kyoto in 1917, and they were invented by a man named Soujiro Nishio,” Yamashita explained, adding that the craftsman had been an employee of the Shimazu Corporation, a manufacturer that made plant models.

Nishio is said to have made the first food models in November 1917 and eventually formed Nishio Production Company, which made the first food models. According to legend, it wasn’t until a department store in Okayama solicited Nishio for food replicas that the models truly took off.

Another theory credits Shirokiya Department Store, the first Japanese department store to have a cafeteria featuring the waxy delights. The historical department store dates as far back as 1662, but it wasn’t until over 200 years later that displaying the items on their menus would become part of the store’s marketing approach.

“They had the idea to display a serving of each dish,” an article on sampuru published by Tofugu, a Japanese culture and language blog explains. “But real food could attract bugs and get sad-looking in other ways by the end of the day, and making the food and throwing it away every day wasn’t without expense.” With this dilemma, the department store tapped Tsutomu Sudo, an anatomical maker of human body parts and animals.

A third theory cites Takizo Iwasaki, a man who ran a bento shop in Osaka, as becoming the first sampuru maker. According to Yamashita, Iwasaki made bento lunches and, after a bit of trial and error, created a model of an omelet that was so realistic when he showed it to his wife, she wasn’t able to tell the fluffy egg dish from the real thing.

Known today as the “father of the fake food model industry,” Iwasaki’s company — formerly the Iwasaki Group, now known as Iwasaki Be-I — is said to account for 60% of today's Japanese sampuru market.

Those first models were made of wax, but today’s models are made of plastic.

While the valuation of sampuru is high, most of its manufacturers still largely custom-make the models by hand. The handcrafted process of the food models is one of minute detail and artisanship.

A restaurant soliciting replicas of its menu items will typically freeze their dishes so that a manufacturer can begin the process of creating a casting mold.

For its approach to constructing replica foods, Iwasaki Be-I states on its site that it follows a “not widely known” step-by-step process. Starting with the creation of a mold made by duplicating the rough surfaces of food, the manufacturer then slowly fills the mold with silicone and a colored resin. After heartening the material in an oven, the silicone is removed from the model and then painted with airbrushes and paintbrushes.

It doesn’t end there, though. After all, the key to any dish is presentation. Whether it’s how your side of fries will be placed alongside a burger stacked high with toppings, or the lacquered look of unagi over a bowl of rice, food models are set in a way to duplicate how a dish will be served.

Beyond whetting appetites, food models have also fostered cultural exchange and expansion around the world.

In an interview with TODAY, Seigo Kozakai, the CEO of Iwasaki Mokei (not to be confused with Iwasaki Be-I) underlined the impact sampuru has had in aiding culinary expansion and collaboration around the globe. “Sampurus grew proportionally to the growth and development of Japanese restaurants,” Kozakai remarked. “After the 1940s, when Western food culture came to Japan, these sampurus gave visual reassurance to the Japanese people who had not seen many of these dishes before. Since then, it was recognized that sampurus were effective and became what is known today.”

Beyond broadening American palates, sampuru has played a significant part in imparting an understanding of food as an art form in itself. A 1985 article published in the New York Times described sampuru as an example of a “pure Tokyo style of traditional craftsmanship” that had fascinated the art world so much that it was included in an exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. One anecdote from the piece recalled how a visitor at the museum had discovered a piece of fur on a plastic kiwi fruit the visitor had taken as “quite real.” Years later, by 1990, examples of the Japanese food samples were part of a permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. And the fascination with food replicas as art continues. In mid-May, the Japan House Los Angeles hosted Seigo Kozakai for a presentation on the craftsmanship and business of these food replicas.

With its ability to visually communicate the texture and flavor profile of foods, sampuru has long served as an ambassador of new culinary experiences for consumers worldwide. Today, they give nonverbal children and people the ability to communicate their desires, offer tourists an opportunity to venture outside of their cultural comforts, and — with their numerous displays in window shops — brighten the streets of our world.