The Fed’s diversity problem: Too few Federal Reserve Bank directors are women of color

The Federal Reserve says diversity and inclusion in the economy is important, but its own leadership is largely made up of white men.

This is no secret, and the Fed has actively been engaging with the topic of diversity. In the summer of 2020, leadership at the Federal Reserve committed to taking a strong look at inequality in the U.S. economy. The leadership has continued this engagement through the ongoing series "Racism and the Economy," a range of events that acknowledge the connections between systemic racism and American economic life, through education and listening to communities adversely affected.

While these are steps in the right direction, more must be done to address rising and unprecedented levels of inequality imbued with systemic racism. The U.S. central banking system must not only continue to reflect inwardly, it also has to take action to get its own leadership to where it needs to be—especially with regard to the representation of women of color.

One important leadership position at the Fed, and one that has not received much attention, is that of the boards of directors of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks.

The Fed’s governance structure was the outcome of a compromise, dating back to its creation more than a century ago, between those who wanted a single, strong central bank and those who wanted multiple small banks spread throughout the country. The result divided power among 12 regional Reserve Banks and an office in Washington, D.C.

Each of the 12 Reserve Banks has nine directors. Though they don’t have as much authority as a traditional corporation’s board of directors, the directors of the Federal Reserve Banks do have at least two influential responsibilities. First, and most importantly, with approval from the Fed in Washington, six directors at each bank appoint the presidents of the Reserve Banks. Second, all directors advise the Reserve Bank presidents on issues affecting the local economy.

Together, their influence on the economy can’t be overstated: The Fed supervises and regulates much of the financial system and influences interest rates, which have a direct effect on businesses and households not just in the U.S., but globally.

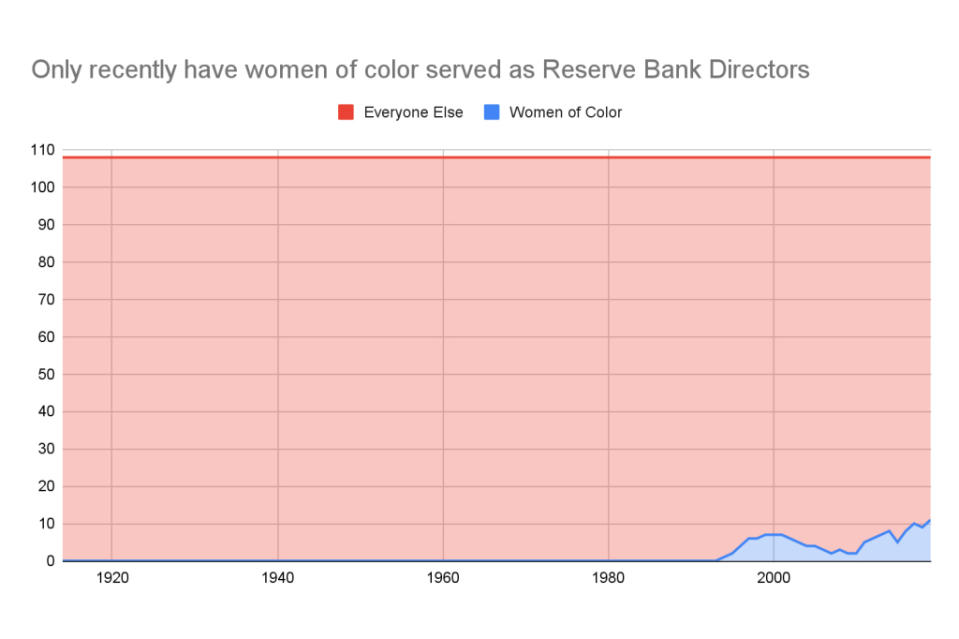

Still, today women of color account for only 14% of the directors, even though people of color make up over a third of the population and are the group most adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because the process of selecting the Reserve Bank directors is outlined in the Federal Reserve Act itself, any fundamental changes would have to be made by Congress. However, the last time Congress made a significant change to the Federal Reserve Act, it required that the Fed and other financial regulators "take affirmative steps to seek diversity in the workforce…at all levels."

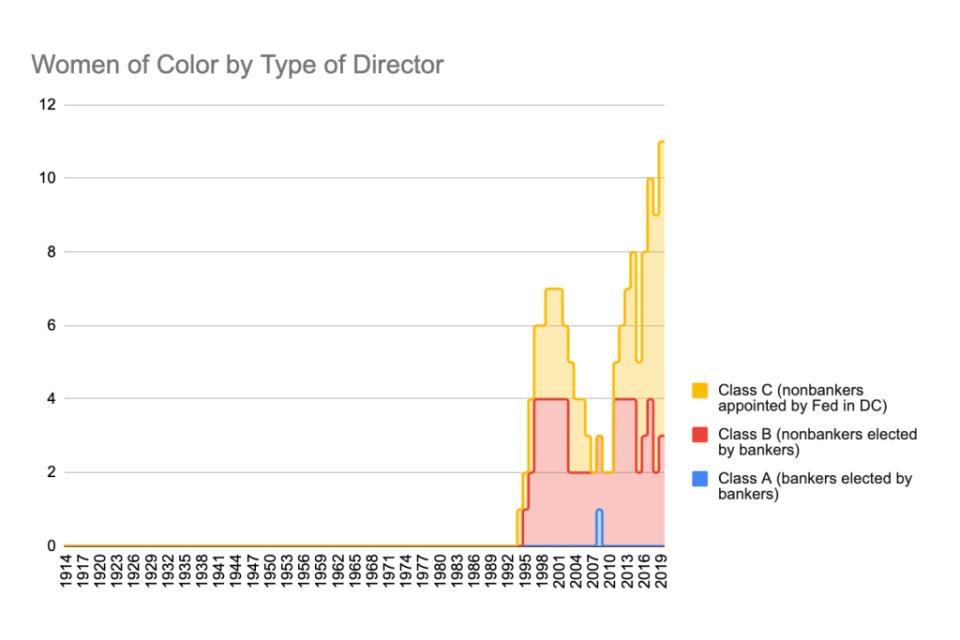

There remains much to do for the Fed to satisfy this requirement. The Fed office in Washington appoints three members to each regional board, and the local banking community elects the other six. The Fed should use its appointment power to elevate women of color who bring unique and critical perspectives. The banking community, meanwhile, has an even larger role to play. Bank leaders should elect women of color from within their ranks to serve at the Fed, using the same criteria that is applied when electing white bankers.

On day one of his presidency, President Biden signed an executive order committing to advance racial equity. He should nominate someone to the Board of Governors who commits to working with the Reserve Banks to increase the number of women of color serving on the board of directors.

The first woman appointed to the board of directors at a Federal Reserve Bank was Jean Crockett in 1977; the first woman of color wasn't appointed until 1994. The economic depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected women more than men, leading some to call it a she-cession. Although the full list of directors for 2020 will not be released until next month, the Fed’s website does list demographics of the current boards. This website shows there are only 46 women directors today, and only 15 of those women are minorities. And since 1994, on average less than 10% of the directors of the 12 Fed Reserve Banks have been women of color, as the chart below illustrates. Those numbers reflect the continued gap between the large number of women of color serving as "essential workers" in the economy and the very small number who are influential in its governance.

Our assessment of diversity of gender and race, using a new biographical data set of the more than 2,600 directors at the Reserve Banks from 1913 through 2019, also illustrates the unacceptably slow increase in the number of women of color directors.

In addition, none of the directors who are women of color are bankers, and the number elected by bankers has plateaued in recent decades. Appointees from the Fed in D.C. fully account for the increase in representation. So although we applaud the Reserve Banks overall for their progress, banks who elect the other directors need to step up.

An unfair standard

Using the same data set, we found that on average, the women of color who have become Fed bank directors have higher levels of skills, credentials, and experience than their white male counterparts. For example, since 1987, 86% of women of color directors have held advanced degrees, compared to only 63% of white directors. It is apparent that consciously or not, those who select these women of color are holding them to a higher, unfair standard. (This problem isn’t unique to the Fed: Studies have shown that in other areas of the economy, women of color in leadership positions have more experience than their white male counterparts.)

Those who influence the direction of the American economy should look like America, since the Fed’s mandate is to create a working economy for all Americans, not just for those who are currently overrepresented on the boards of directors—that is, white men. Americans who face the brunt of racism and sexism should not have to outperform their white male counterparts in order to contribute as leaders who guide the economy.

The Fed is not blind to this issue. Former Minneapolis Fed president Narayana Kocherlakota sounded the alarm last year about the lack of diversity among Fed officials, and about the role of expectations of higher credentials for Reserve Bank presidents. The Fed should invest resources in amending this practice to improve its selection of leadership.

The good news is that the Fed can rectify this issue speedily. A full third of the 108 director positions at the Reserve Banks are up for appointment or election every year. Increasing the number of women of color could be done quickly.

The Fed is one of the most important institutions guiding the U.S. economy out of this crisis. The recovery won’t be complete without the voices of more women of color.

Fanta Traore is cofounder and CEO of the Sadie Collective, which supports Black women in economics and related fields. Kaleb Nygaard is a senior research associate at the Yale Program on Financial Stability. Both are former staffers at the Federal Reserve.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com