What federal courts have said about local library book bans

A row of library books. (Getty)

The Autauga-Prattville Public Library’s future turned on a Feb. 8 meeting of its board of trustees.

New board members appointed following a mass resignation late last year, most of whom were appointed by county commissioners, wasted little time in refashioning the library in their image — one that suited Clean Up Alabama, a group that was instrumental for installing them as members of the library board.

In one of their first official acts, board members restricted books for people younger than 17 that involve sex and obscenity as well as sexual orientation and gender identity. The members also shifted $2,000 from the library’s marketing and advertising budget to hire attorney Laura Clark, the interim president of a conservative nonprofit called the Alabama Center for Law and Liberty, to represent them in legal matters instead of using the services of the city attorney.

“I was advised by the city attorney that we needed an attorney,” said Ray Boles, the new chair of the library board. “We were just advised that we needed an attorney, so we went out and got an attorney. She is a constitutional attorney. That is why we picked her.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

With an attorney on retainer, board members appear ready to take on any legal challenges.

“We will go back through the budget and find the funds,” Boles said when asked about future legal costs, adding that the library budget totals $400,000.

The meeting was the culmination of a months-long dispute over the contents of the library in Prattville, a suburb of Montgomery. Clean Up Alabama and Read Freely Alabama, which has opposed attempts to limit access to books, sparred publicly about content in the library. For months, supporters from both sides attended city council and county commission meetings hoping to earn the support of elected officials responsible for appointing the members of the library board.

Autauga-Prattville Public Library Director Andrew Foster demonstrates how a magnifying machine works in the Alabama section of the library on Feb. 23, 2024. (Ralph Chapoco/Alabama Reflector)

The tension had not abated at the Feb. 8 meeting at Prattville City Hall. Members of Clean Up Alabama, who have claimed that books in the library contained sexually explicit content, sat on the right. Members of Read Freely Alabama, who accuse Clean Up Alabama of trying to eliminate books with LGBTQ+ themes, sat on the left.

“I just want to say that I appreciate everyone’s efforts to protect the innocence of children,” said Chuk Shirley, a member of Clean Up Alabama. “Any time a policy needs to be adjusted, we change policies all the time for many different reasons. Obviously, there has been a rising need with a growing number of published books lately that are targeted to children.”

Members of Read Freely Alabama expressed anger and frustration at the new policies that were adopted.

“The act of selectively excluding or segregating certain books based on personal beliefs harms the values of free expression and equal access to information,” said Amber Frey, a Read Freely Alabama member.

Members of Clean Up Alabama did not respond to requests for comment outside statements made at public meetings.

Clark, who was recently appointed to represent the board, declined comment as well.

Read Freely Alabama, meanwhile, is planning to take the battle to court, according to Angie Hayden, a spokesperson for the group.

“I think we have known from the beginning this is where this is headed,” she said. “I think that Clean Up Alabama, and Moms for Liberty, always intended for Alabama to be the test case of the country. And for them to accomplish what they want, it will have to go to the courts.”

Similar cases have ended up in federal courts over the past four decades. The question is how aggressively library board members may apply their selection criteria to circulation materials before violating the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The First Amendment and library content

The U.S. Supreme Court building in 2020. Federal courts have generally frowned upon attempts by libraries to restrict ideologically-based content. But the high court split on a 1982 case about the removal of books like Richard Wright’s “Black Boy” and Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse Five.” (Al Drago/Getty Images)

Library boards set policies that guide the operations of a library. They have a broad latitude to determine what materials belong in a collection.

“(A board) can decide if it wants greater racial and gender diversity, to ensure that the entire community is better served,” said Kenneth Paulson, director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. “It can decide that there needs to be a greater emphasis on Alabama history and order more books on those topics. There is no problem with a local library board helping set standards for librarians in an effort to better meet the needs of the public.”

If a library board wants more books about soccer because it has become more popular than basketball, it can do so with little push back from the public.

But a board’s powers are not absolute, and cannot cross the line into discrimination.

“The stakes definitely get higher, and the situation gets different when you have a situation when nonprofessional government overseers are coming in and making decisions on what I would presume are ideological grounds,” said Gregory Magarian, a professor at the Washington University School of Law in St. Louis, who specializes in free speech, the law of politics, and law and religion. “First Amendment law frowns particularly hard on viewpoint-based discrimination by government actors, and I think removal of titles from library collections based on political viewpoints (or) ideological viewpoints would constitute viewpoint-based discrimination.”

Challenges to library content have reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1982’s Island Trees School District v. Pico, the court split over a question over the extent of the powers of an entity overseeing a library to limit content.

In that case, the Island Trees Union Free School District Board of Education, located on Long Island, New York, tried to remove books from its junior high and high school libraries against the recommendation of parents and school staff.

Some of the titles included “Black Boy” by Richard Wright, an autobiography covering Wright’s childhood in the South and his life as a young adult in Chicago. The book contains childhood hunger, beatings, and racist treatment.

Another was “Slaughterhouse Five” by Kurt Vonnegut, a novel whose protagonist survives the firebombing of Dresden, Germany by British and American air forces in February 1945.

School board members said the books were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy.”

A group of students filed a lawsuit in federal court. A lower court upheld the board’s decision. The plaintiffs appealed the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and won. Board members then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

A plurality of justices ruled that there were limits to what books could be removed from libraries, but a 4-4 split meant the case did not create binding precedent. Justice William Brennan, writing the plurality opinion, said governing boards could not remove titles “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” Chief Justice Warren Berger wrote in dissent that “elected officials express the views of their community; they may err, of course, and the voters may remove them.”

There have been other censorship cases since then. In the 1995 case of Case v. Unified School District, a school board in Olathe, Kansas, sought to remove “Annie on My Mind” from the school library, a novel about two teenage girls whose friendship evolves into romance. The book had been part of the general collection since the early 1980s.

A federal district court ruled that the school board’s action amounted to a constitutional violation because the “substantial motivation” in the removal was a disagreement with the ideas expressed in the book.

In Sund v. City of Wichita Falls in 2000, the city council of Wichita Falls passed a resolution removing books from the children’s section of the library and reshelving them in the adult section because of a petition from 300 library card holders. As a result, titles such as “Daddy’s Roommate” and “Heather Has Two Mommies,” both of which had LGBTQ+ themes, were removed.

The court ruled the actions of the school board were unconstitutional and violated people’s free speech rights, arguing that the library is a public forum and that books could not be moved because parents disagreed with the content, or the views expressed in the books.

In Counts, et al. v. Cedarville School District in 2003, an Arkansas school district wanted to remove Harry Potter books from general circulation and place them behind the counter with access only to those who received their parents’ permission. A district court ruled that the practice was unconstitutional, violating students’ rights to access materials in the school library.

Prattville

Central to the controversy at Autauga-Prattville Public Library is whether the current library board is using claims of sexually explicit content to mask attacks on books with beliefs or ideologies they disagree with.

Sexually explicit materials may be removed from the shelves. But the materials must meet a standard the law has identified for a work to be considered, either depictions or descriptions of acts whose offensiveness rises to a specific threshold.

The materials must also be reviewed in their totality, not isolated to a specific scene or section.

“There is absolutely no way that a court in the country would hold that (the novel) ‘The Kite Runner’ is obscene,” Magarian said. “There is no way that any court in the country would hold that anything by (the novelist) D.H. Lawrence is obscene. Any work of literature of substantial renown, nothing like that would qualify legally as obscene.”

Most free speech experts interviewed said they doubt most, if any, of the materials in the collection of any library meet legal definitions of obscenity.

“Can someone give me an example of a children’s book that teaches the Kama Sutra?” Paulson said. “I missed that part of the ‘Gingerbread Man.’” What book is sexually explicit in a children’s library?”

The Autauga-Prattville Library Board’s policies state that “For the avoidance of doubt, the library shall not purchase or otherwise acquire any material advertised for consumers ages 17 and under which contain content including, but not limited to, obscenity, sexual conduct, sexual intercourse, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender discordance.” The policy also said that age-appropriate materials “concerning biology, human anatomy or religion are exempt from this rule.”

Magarian, who reviewed the library board’s new policies on selection criteria, said they are vague.

The professor wrote in an email that almost every resource that discusses human beings deals with gender identity. He said the selection criteria points to sexual orientation and gender identity as grounds for restricting access to materials, which amounts to viewpoint discrimination, as does allowing books on religion but not on those subjects.

Removing the books, or any materials that some deem inappropriate, limits access for others who want to read or obtain information contained with the materials, said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of intellectual freedom at the American Library Association.

“Librarians are trained,” Caldwell-Stone said. “They have a code of ethics. They are trained in developing collections, curating collections, that meet the information needs of everyone in the community, and to do that while removing their personal beliefs out of it.”

In terms of sexually explicit materials, many question if the library should be the focus in a world where children can obtain sexually based content easily with a few clicks of their mouse. The dangers, Paulson and Magarian said, are not within libraries but found in personal computers.

The parents are the people who should decide whether a book in a collection is appropriate for their children to read, not the government, according to Paulson.

The culture wars

The Prattville battle is a single front along a battle line that stretches throughout the country in the nation’s ongoing culture wars.

Library Associate Tammy Bear inventories books at the Autauga-Prattville Public Library on Feb. 23, 2024. (Ralph Chapoco/ Alabama Reflector)

The ALA tracks requests and demands by the public to censure books from public libraries since 1990. Typically, the ALA documents between 300 to 400 incidents annually in which people have requested books they borrowed to be removed.

That figure has risen dramatically since the fall of 2020. In 2023, the ALA tabulated more than 1,200 instances of people requesting books be removed from circulation in libraries and schools throughout the country, targeting about 2,700 unique titles.

“We have gone from a situation where we had a parent raising a concern about a book with a librarian or a teacher, to a situation where we have advocacy groups going to the library with lists of sometimes hundreds of books that they have been told are bad books by social media or websites, demanding their removal, sometimes without ever looking at or reading the book,” Caldwell-Stone said.

Many of the books called into question deal with gender identity or sexual orientation, the lives or experiences of people who are LGBTQ+.

The controversy over the content in Prattville began last year when a parent borrowed a pronoun book from the library’s shelves and realized the book contained inclusive pronouns other than male and female designations.

Since then, Hannah Rees and other members of Clean Up Alabama have staged protests at city council and county commission meetings, reading passages from books they believe contained sexually explicit content.

They also staged protests at meetings of the Alabama Public Library Service, deploying the same tactics of reading passages from books they believed are inappropriate for children. APLS also plans to solicit feedback from the public about the books they object to and lay out a process for reviewing them and voted earlier this year to not renew its membership in the ALA.

The Autauga-Prattville Library Board resigned en masse at the end of last year in protest of the county commission making an appointment to the board without consulting them. Subsequent appointments all favored Clean Up Alabama.

One member appointed by the city council late last year, Christie Sellers, resigned in a letter sent before the Feb. 8 meeting.

“The library should be a sanctuary for intellectual and literary freedom, providing diverse perspectives and ideas that equally represent a cross-section of the population and not a single-minded posture based on a political agenda,” Sellers wrote. “Unfortunately, it appears that the current board is veering away from this fundamental principle, favoring a course of action that compromises the very essence of these democratic values.”

She also took issue with the selection criteria, which she said, “evokes blatant censorship of books within our current library collection. Censorship of this nature is a direct violation of the trust bestowed upon the Library Board by the community.”

Opposition

Read Freely Alabama objects to both the policies and the manner in which they were adopted. Hayden said it represents not only a clear free speech violation but puts the library in a strange position.

“Books like ‘Heather Has Two Mommies’ and a book with two male penguins, they raise an egg together, those books are now going to be in the adult section, oddly enough,” she said. “Which means now little children will have to go into the adult section where all the sexually explicit books actually are to access their ‘Heather Has Two Mommies.’”

The group also objected to the policies the board codified earlier this month, arguing the way they were adopted was vague and gave no clear sense of how existing by-laws were reviewed or amended.

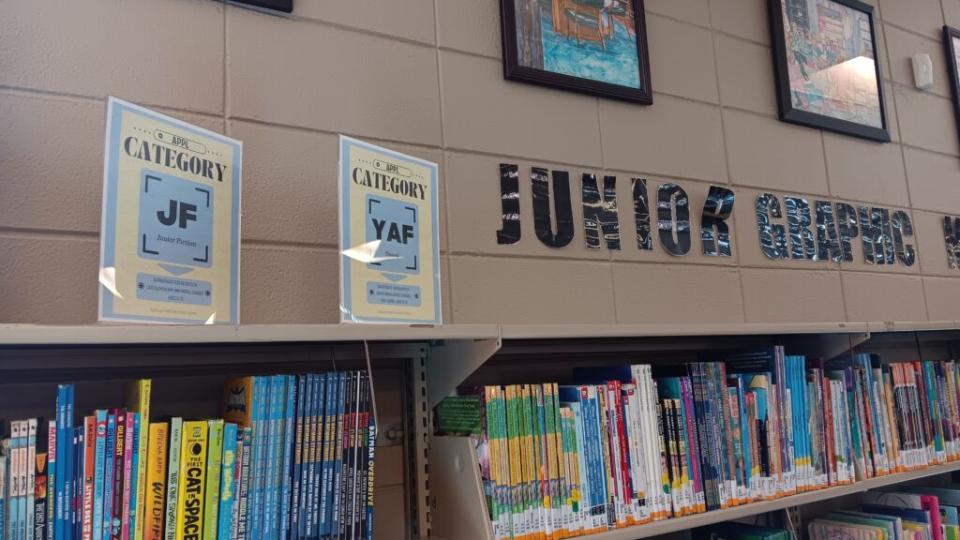

Signs are posted in the young adult section of the Autauga-Prattville Public Library on Feb. 23, 2024. (Ralph Chapoco/ Alabama Reflector)

The new bylaws and policies are the work of two members of the board appointed by the county at the end of 2023, Rachel Daniels and David Darr. According to Darr, the two sent their drafts to the group before the meeting. He and Daniels sent out their drafts before the meeting after receiving ideas from other members of the board about what should be included, as well as input from the city attorney.

“I got the ball rolling on the bylaws, and she got the ball rolling on the policies,” Darr said in an interview after the February meeting concluded.

Read Freely Alabama believes the process sidestepped the accepted process for revising or updating policies for the library.

“They did not engage with any library experts in Prattville,” Hayden said. “They did not engage the staff or the library director of the Prattville library, which resulted in policies that ran contrary to the ideals of constitutional librarianship. And it would seem they allowed Clean Up Alabama to have undue influence.”

Board members said they followed the appropriate process for developing the bylaws and the policies for the library they voted to approve during the meeting.

“I am very familiar with the law and the meeting, there was not a violation there,” Clark said. “I am also very familiar with the policies and the bylaws, there was not a violation there either.”

The policy allows staff to remove books that meet the criteria. Books remaining that board members identify as sexually explicit will be labeled with a red warning sticker “prominently on the binding of any book.”

For Hayden, the books that Clean Up Alabama are targeting have a role to play in society and belong on the shelves of the local library because they meet the needs of some in the community.

“The public library is supposed to be there to serve all taxpayers,” she said. “I am a taxpayer. I have a daughter who is openly gay, and she should be able to go in and access books that represent her, her family. Gay partners with children should be able to go into the library and find books that look like their family, and to prohibit them from doing that is clearly unconstitutional.”

The post What federal courts have said about local library book bans appeared first on Alabama Reflector.