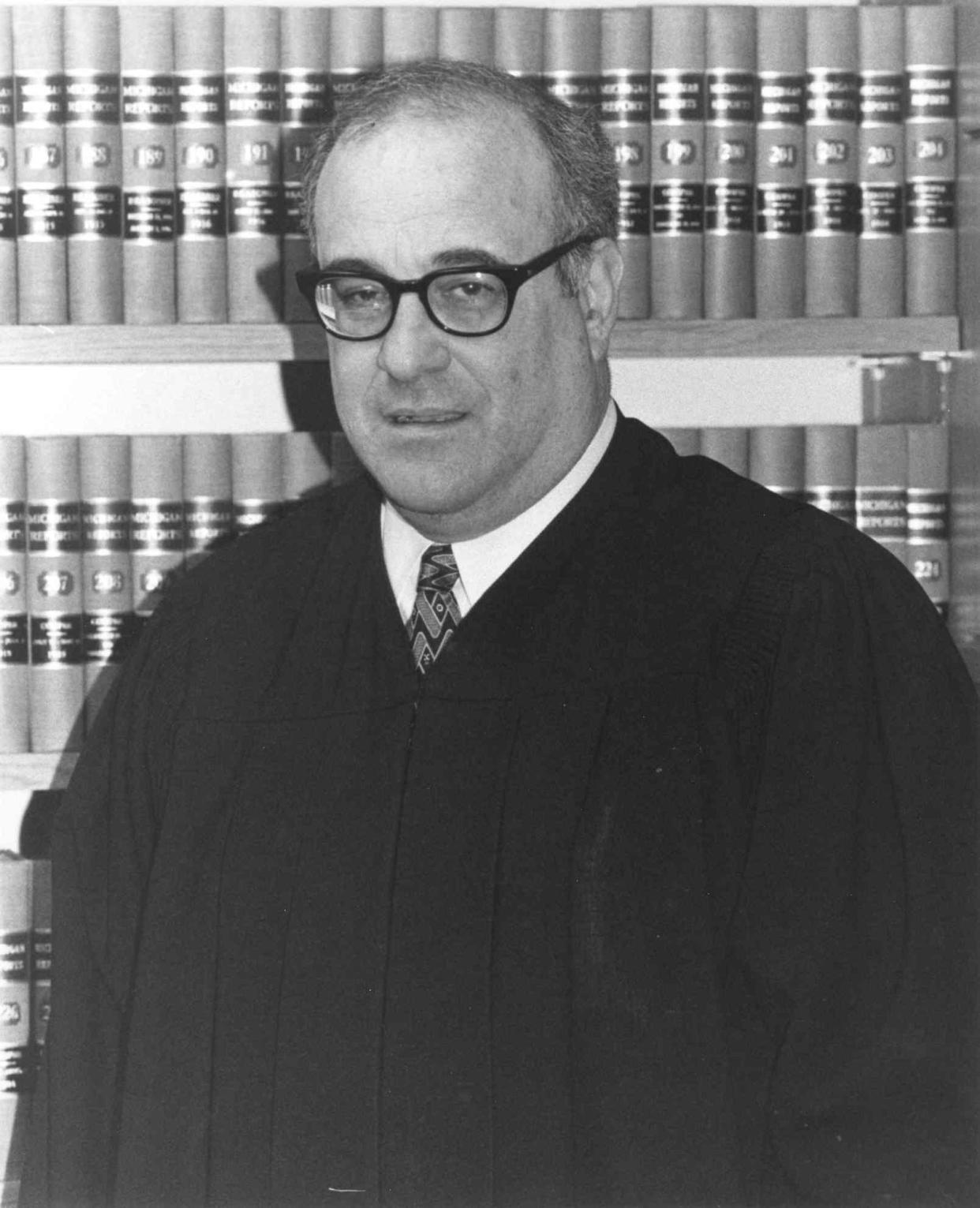

Federal Judge Arthur Tarnow dies at 79: 'The most truly human person in the courthouse'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

U.S. District Judge Arthur Tarnow had a way with words — and his courtroom was rarely dull because of it.

He was humorous, blunt, compassionate.

For 24 years, he used those traits to make people feel comfortable in the often intimidating federal court system, and was known to catch many off guard with his colorful remarks — like telling a defendant who was upset about his jail conditions, “Well, the Pontchartrain Hotel is full.”

Tarnow, a witty, knowledgeable and humble jurist who believed in second chances, treated prominent and common folks the same, preferred loose cardigans to stiff suits, and ruled on everything from child slavery and sex escort cases to public corruption and civil rights, died Friday. He was 79.

“He was the most truly human person in the courthouse,” said longtime criminal defense attorney Bill Swor, whose relationship with Tarnow dates back 40 years, when the judge was a lawyer with the state's Appellate Defender's Office, and the two played in a lawyer softball league together.

“He understood the power his office held, and truly wanted to use his superpowers for good,” said Swor, noting Tarnow had a well-kept secret.

"He was always the smartest guy in the room," Swor said, "but never let anyone know he knew it."

Tarnow, a Detroit native and onetime preeminent criminal appellate lawyer who was appointed to the federal bench in 1998, died Friday morning at Henry Ford Hospital, where he was being treated for heart issues.

“Our whole court grieves at the loss of Judge Arthur Tarnow,” Chief U.S. District Judge Denise Page Hood said in a statement. “Judge Tarnow was an excellent judge, fair in all ways and ever cognizant of the hurdles facing men and women returning to the community after serving a sentence in prison."

She added: "He was also a loyal friend and a had a sense of humor that could sometimes catch you off guard or was just plain corny.”

Swor can attest to that, as he recalled a comment that Tarnow once made as he approached him at the bench during a proceeding.

"He said to me, 'I know where you got that tie,' " Swor recalled, noting the tie was nothing special.

Amused, Swor asked the judge, "You do? So where did I get it?"

"Your closet," Tarnow replied.

More: Veteran Wayne County prosecutor dies: 'She was a hell of a lawyer'

More: Retired federal judge Marianne Battani dies after long illness: 'We have lost a gem'

This is the Tarnow that hundreds of defendants and lawyers caught glimpses of during his distinguished career on the bench, where he delivered opinions in landmark cases, sometimes stirring controversy with his decisions.

For example, Tarnow took some heat for granting compassionate release to numerous inmates during the COVID-19 pandemic, including a convicted murderer whom Tarnow had previously given two life terms. That inmate was locked back up after prosecutors appealed.

Tarnow, though, issued a rare clarification in that case, explaining that he freed the man — who had already served 22 years — because he had turned his life around in prison and presented "compelling and extraordinary" reasons for releasing him.

"As this court often reminds the attorneys who appear before it in compassionate release hearings, its goal ... is to evaluate defendants, not as they were at the time of their original sentencing, but as they are now," Tarnow wrote in his clarification.

Perhaps this is what Tarnow is remembered for most — his willingness to believe that people could change, and were worthy of second chances.

"Judge Tarnow had a tough exterior but a heart of gold. He was always interested in giving offenders second chances," said former U.S. Attorney Barbara McQuade. "He devoted his life to serving indigent defendants, and that empathy for the least powerful members of society came through in all of his work."

Like many others in the courthouse, McQuade was no stranger to Tarnow's deadpan humor.

"His dry wit could sometimes knock you off balance, but once you spent some time with him, you realized that he used humor to put people at ease in the courtroom," said McQuade, adding the two connected over their shared love of the Detroit Tigers. "We will miss him."

Longtime criminal defense attorney Mike Rataj echoed those sentiments, noting defense lawyers often relished the opportunity to have their cases heard by Tarnow.

"He was a good guy. He was extremely intelligent and fair," Rataj said. "We're going to miss him."

Tarnow, the son of a successful electrical supply business owner, grew up on the edge of the Boston Edison District. Neighbors included famed UAW President Walter Reuther, whose driver occasionally drove Tarnow to school in the labor leader’s bulletproof Packard.

He graduated from Mumford High School in 1959, then enrolled at the University of Michigan, returning home a year later to attend Wayne State University. There, he earned his bachelor's degree in 1963 and went on to earn his law degree with honors in 1965.

“I chose law, I think, to try to help people,” Tarnow told the federal court’s historical society in a 2017 interview.

After law school, Tarnow traveled the world, working at universities in Australia and New Guinea, and visiting places like Thailand, Vietnam, Hong Kong, the Philippines, several African countries, Israel and London.

Upon his return to the states in the late 1960s, Tarnow was recruited by law school friends to work for the Legal Aid and Defender Office in Detroit, where he represented criminal defendants in their legal appeals. In 1970, Tarnow became the first full-time director of the newly created State Appellate Defender’s Office.

The next year, he married Mary Jacqueline Beaubien, a nurse whom he met through a friend. They had two sons.

In 1972, Tarnow expressed an interest in politics, though it was brief. He ran for Detroit Recorder’s Court but lost the general election, so he spent the next 26 years in private practice.

In 1997 came his big career jump.

President Bill Clinton nominated Tarnow to the federal bench in Detroit, where he would oversee numerous high-profile cases, but remain humble in the process. There was no ego to deal with, many who knew him said.

He was often spotted walking downtown alone and buying his lunch, chose to keep his first-floor courtroom rather than move higher up - he didn't like elevators and enjoyed being across the hall from the candy store - and installed two miniature cowbells in the jury box of his courtroom so jurors could let him know when it was time for a restroom break.

“I was overwhelmed,” Tarnow said of his early days on the bench. “It takes a lot of time to become an effective federal judge. The key thing is to listen and recognize that you don’t know everything. Curiosity is important.”

Tarnow handled several high-profile cases over the years.

In 1999, he temporarily blocked a new state law that would have banned so-called partial birth abortions and imposed a maximum penalty of up to life in prison for violations.

In 2006, Tarnow ruled that proponents of Proposal 2 tricked voters into signing petitions to put an anti-affirmative measure on the statewide ballot. While he concluded that the deception didn’t violate federal discrimination laws, he said those who were misled could rectify the situation by voting against the issue in the November election. The decision was upheld on appeal and Michigan voters went on to approve the measure, which banned race and gender preferences in government hiring and public-university admissions.

In 2011, Tarnow presided over the sensational Miami Companions sex-ring case, which involved a nationwide escort service that sold sex for $500 an hour, had a black book of 3,000 customers and raked in more than $4 million, with metro Detroit being among its busiest ports.

In 2014, Tarnow oversaw the child slavery case of a U-M janitor who was convicted of sneaking four west African children into the U.S., pretending they were his own, and abusing them with broomsticks, a toilet plunger and ice scraper. Tarnow sentenced the man to 11 years in prison, but an appeals court struck down the slavery conviction, forcing Tarnow to reduce the man's sentence to 21 months in prison.

" 'You got a huge break," Tarnow told the defendant, adding: "I trust that you've learned your lesson as to your form of, quote unquote, 'discipline.' "

Asked in 2018 how he would like to be remembered, Tarnow said: “Being a public servant with great power is a large responsibility. It requires patience, the ability to listen to the parties, lawyers and law clerks, and a sense of fairness.”

He is survived by his wife, Jackie; sons Tom and Andrew; a brother, Robert; a sister, Adrienne Goldbaum, and two grandchildren.

Due to COVID-19, the family is hoping to hold a memorial gathering this summer.

Contact Tresa Baldas: tbaldas@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Federal Judge Arthur Tarnow dies: 'most human person in courthouse'