Federal scientists make carbon-free energy breakthrough with nuclear fusion research: reports

Federal scientists have reportedly made a breakthrough in the potential for nuclear fusion as a carbon-free power source.

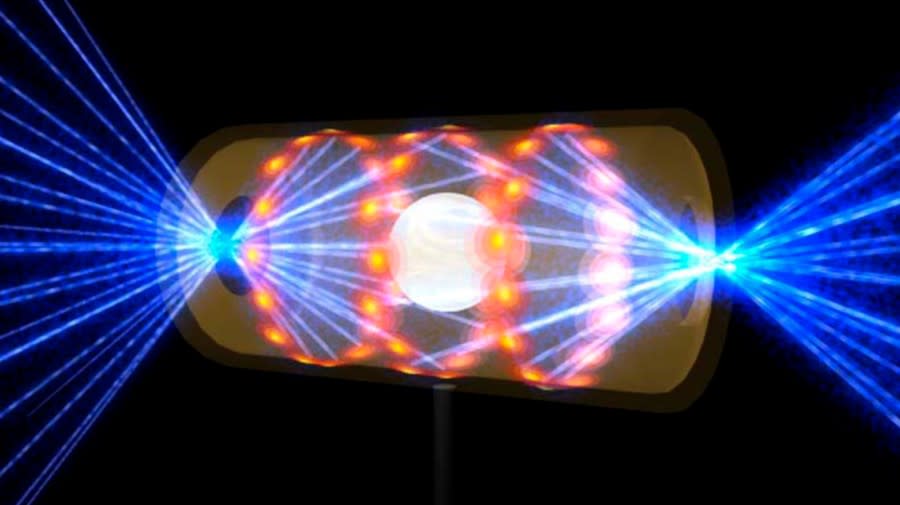

The Financial Times reported on Sunday that scientists with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory produced more energy than was consumed in a fusion reaction for the first time. The Washington Post and Bloomberg separately confirmed the Times’s reporting.

Nuclear fusion refers to fusing atoms together to produce energy. The type of nuclear energy that is commonly used today does the opposite, deriving energy from splitting atoms apart.

For decades, scientists have sought to advance nuclear fusion as a carbon-free source of energy that also doesn’t produce the radioactive waste that occurs when atoms are split apart.

Breanna Bishop, a spokesperson for the national lab, declined to confirm the reports or provide details on what the lab has achieved.

“Our analysis is still ongoing, so we’re unable to provide details or confirmation at this time. We look forward to sharing more tomorrow when that process is complete,” she said in an email.

However, the Energy Department is slated to hold a press conference Tuesday on a “major scientific breakthrough.”

Paul Dabbar, who was the Energy Department’s Under Secretary for Science during the Trump administration described the reported development as a “giant jump” forward.

He acknowledged that more research is needed, but said this step was the “hardest” one to achieve.

“It’s a major science accomplishment.” said Dabbar, who is now a distinguished visiting fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. “It shows a path that this is doable with at least one technology and probably many others.”

Nuclear fusion may not be totally radiation free. Nuclear fusion does create byproducts that have “low grade radiation” but that is much less significant than what’s created by current nuclear energy, said Carolyn Kuranz, an associate professor of nuclear engineering and radiological sciences at the University of Michigan.

Kuranz also said that in nuclear fusion, these byproducts would actually stay at the power plant site and not require storage in the way that nuclear waste currently does.

Deploying fusion energy on a large scale could be a significant advancement in combating climate change, but the reported breakthrough would just be one step on the way there.

If scientists did make the fusion breakthrough, it still could be years before such technology is deployed commercially.

Dabbar estimated that the first commercial demonstration fusion reactors could spring up between 2030 and 2035 and large-scale deployment could come a few years after that. But he said it’s something that could help the Biden administration with the later years of its goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

“It takes a long time for energy systems to go from testing to full-scale deployment,” he said.

“The path for fusion is kind of similar to what we’ve seen with those other technologies,” he added, referring to the escalation of solar, electric vehicle and battery technologies.

Kuranz, meanwhile, said that nuclear fusion is important because it would add another carbon-free source to our energy mix.

“The demand for energy is going to increase as population grows. I think we need to have a variety of energy sources,” Kuranz said.

—Updated at 4:53 p.m.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.