The Feds Aren’t Just Going After Google and Amazon. They’re Suing the Garbage Internet.

Shopping for dog food shouldn’t be this hard. If you’re searching on Google or Amazon for your pet’s next meal, you wind up inundated with a deluge of sponsored results.

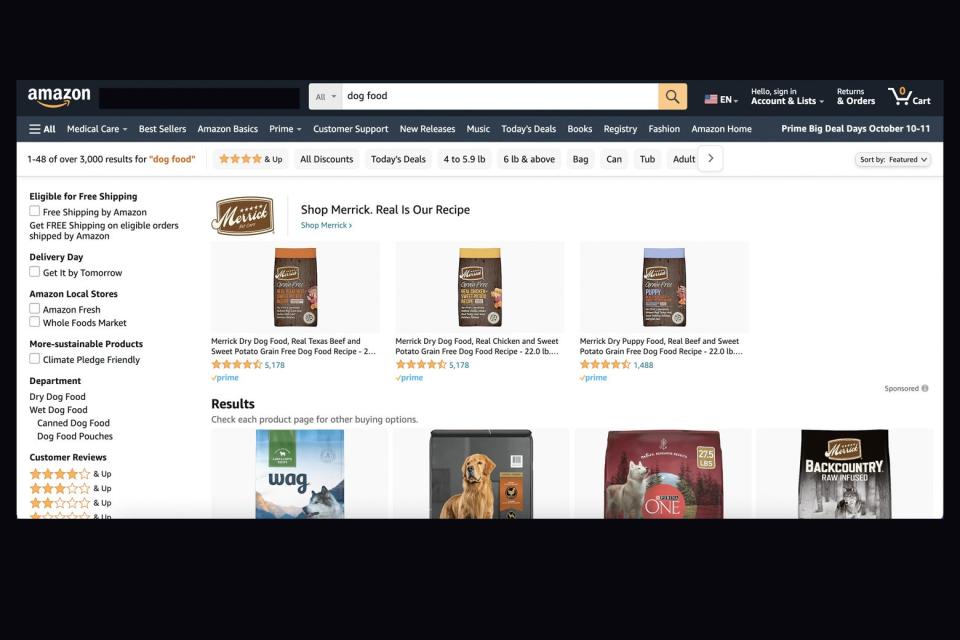

On Amazon, this search elicits a wide sponsored display for Merrick dog food. One row lower, you’ll find that this prime real estate goes to two more brands—Purina and Blue Buffalo—next to Amazon’s own, called Wag.

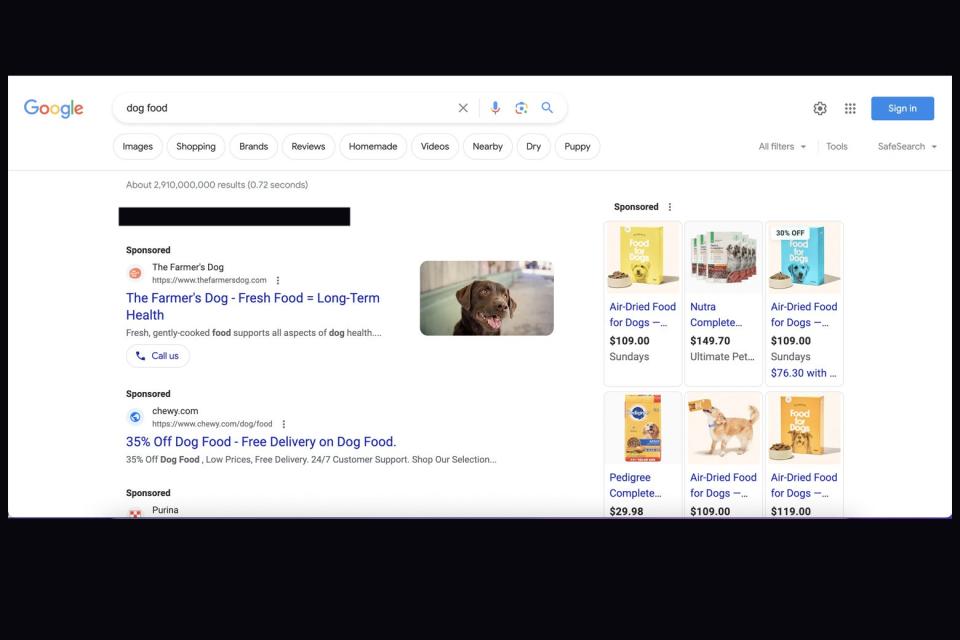

On Google, the experience is somehow much worse.

Not only does the same search yield four sponsored blue-link ads in a row—for Chewy, the Farmer’s Dog, Purina, and something called allforyourfurbaby.com—but a panel on the right-hand side, adjacent to those results, also surfaces even more sponsored dog food brands. You have to scroll past all of that to find the first real result—also for Chewy.

The internet is full of crappy ads. Searching on Google or Amazon these days means you’ll often have to endure half a screen of sponsored results before getting to the so-called organic stuff—what’s selected as the most relevant results by these companies’ black-box algorithms.

The U.S. government thinks that this glut of ads is a symptom of a larger sickness within Amazon and Google. Federal antitrust authorities have alleged in two seismic antitrust cases—one against Google that is currently in court, and another, filed against Amazon this month—that tech giants have abused their monopoly power by illegally blocking out competitors.

Obviously, ads are everywhere on the internet. They pay the bills so people can use popular websites for free. (Cue Mark Zuckerberg: “Senator, we run ads.”) But the feds say Google and Amazon have become practically the only games in town for online search and retail—and they’ve thus created a scenario whereby buying up ad space is the only way for companies to reliably reach users of those ubiquitous services. And they’re selling a lot of ads: In its initial 2020 complaint against Google, the U.S. Department of Justice said the company makes $40 billion in search ads every year. In the recent Amazon complaint from the Federal Trade Commission, Amazon’s ad revenue is currently redacted, a trade secret so big it blots out the sun. (Its overall revenue from “advertising services,” which includes several kinds of ads as well as related services, was around $10 billion in the second quarter.)

In suing Google, the DOJ and 11 states called the search engine the “unchallenged gateway to the internet” for billions of people and noted that, in order to reach them, “countless advertisers must pay a toll.” Similarly, the FTC and 17 states allege that Amazon degraded the quality of its services and “litters its storefront with pay-to-play advertisements.”

This digital payola is how Google and Amazon cash in on their dominance, the government says, but it’s also how it’s made these services palpably worse for everyone. The feds, in other words, are trying to do something about the garbage internet.

The rise of massive internet companies has thrown antitrust enforcement for a loop. In competition law, the so-called consumer welfare standard, by which regulators evaluate harm to consumers, has reigned since the 1980s. This approach to evaluating whether a company is a harmful monopoly focuses on price hikes from anticompetitive mergers or skeevy corporate practices. In contrast, many of the most successful services on the internet are free, subsidized by advertising revenue. They’re not ripping off customers via the sticker price, because there is no price.

The New Brandeis movement, championed by FTC chair Lina Khan and others, has tried to refocus antitrust enforcement moreso around the nature of competition than the specifics of price—that is, the larger economic tidal waves created by whales like Google.

“Most antitrust enforcement is directed at the risk of higher prices to consumers, but with these two-sided platforms like Amazon or Google, consumers don’t pay a monetary price to access the platform,” said Bill Baer, a Brookings Institution fellow who served as assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division during the Obama administration. “Antitrust jurisprudence has to come to grips with what injury there is to competition and consumers where people are not paying a monetary price but are providing incredibly valuable personal data that then allows the platform to monetize it by using it to attract advertisers and retailers.”

The more that Google or Amazon controls its respective domain, the more valuable its user data is in targeted advertising and the more it can charge for placement. “If you’ve got a monopolist that has built a wall around the marketplace, advertisers and retailers arguably pay more to get access to the only show in town,” Baer said.

Then there’s how Amazon and Google allegedly use their size against smaller fish.

Antitrust enforcement deals not only with mergers and acquisitions—the effects of combining large companies—but also with how dominant companies exercise their market power to shut out rivals. That’s the crux of the Google and Amazon cases, in which the government claims that the companies have used illegal tactics to prevent others from fairly competing.

In the Google trial, now in its fourth week, the government says the company illegally struck deals with phone manufacturers and distributors like Apple and Samsung, paying them billions to make Google the default search engine on their mobile devices. As a result, Google has crowded out what little competition remains from the search wars—namely, Microsoft’s Bing and the privacy-focused DuckDuckGo.

Amazon, meanwhile, stands accused of prohibiting sellers from discounting their goods on other platforms and requiring those who want to sell on the Prime subscription bundle—which gives subscribers two-day shipping—to use Amazon’s fulfillment system.

The mechanics of these monopolization cases are different, but prosecutors come to one shared conclusion. As the only game in town, Google and Amazon are resting on their laurels and have made their services worse for users by populating search results with these “pay-to-play” advertisements, which degrade the quality of the user experience—and could possibly make things more expensive if advertisers are passing on their added costs to the consumer.

Google, as the government says, is the gateway to the internet. If so, degrading the quality of that access point rots the core of the web—the more garbage by the doorway, the worse the whole room smells.

The U.S. government doesn’t bring a lot of major monopoly cases. Of course there’s the blockbuster ones: The Supreme Court broke up Standard Oil with a 1910 ruling, and through a settlement broke up the Bell telephone system in 1982.

And there’s the last really big tech case: U.S. v. Microsoft, in which the government claimed that the computing company abused its monopoly in operating systems, with Windows, to give it an advantage in web browsers, with Internet Explorer. The case, which the parties eventually settled, did not result in a breakup of the company, but it likely kept Microsoft’s ambitions at bay in certain consumer-facing sectors.

George Hay, an antitrust law professor at Cornell University and a former DOJ director of economics, said the government will be “struggling to catch their breath” going toe-to-toe with the large legal staffs of big tech firms. “No one’s going to break Google into pieces; no one’s going to break Amazon into pieces,” Hay said. He thinks the government may jump at an opportunity to settle in exchange for some changed practices.

These cases are notoriously difficult to win, said Diana Moss, the director for competition policy at the Progressive Policy Institute, and also its vice president.

“It puts an enormous burden on the government,” said Moss, who until recently was the president of the American Antitrust Institute. “The plaintiffs need to show that the firm not only possessed monopoly power but then used its monopoly power by excluding rivals to maintain it, extend it, or leverage it.”

But as part of that argument, the government’s lawyers will try to demonstrate that although Google and Amazon may not be literally increasing prices for consumers, they’re abusing their market power by degrading the quality of their services.

Baer, the former DOJ antitrust chief, says he’s become more and more frustrated by Amazon search results in recent years—both because of the sponsored results and because of the sellers that Amazon prioritizes in the so-called buy box, where consumers can click to purchase. “I’ve got to search very hard to see what the alternatives are,” he said.

Perhaps in a more roundabout way than if a monopolist raised prices on consumers, if the allegations are correct and Google and Amazon are creating a pay-to-play environment among sellers and advertisers, that could ultimately drive up their costs. “And who pays for that?” Baer said. “Of course it’s the consumer.” Hold your nose.