Feds move to give tribes more say on access to Rattlesnake Mountain in Eastern WA

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The federal government proposes entering an agreement with tribes to give them co-stewardship authority for the use and protection of Rattlesnake Mountain, according to a new memorandum of understanding.

A document setting that goal and agreeing to other steps was recently signed by the Department of Energy and Department of Interior, according to a DOE announcement Wednesday.

“We heard tribal perspectives and we agree on the importance of continued collaboration to incorporate tribal knowledge and expertise in future stewardship of this important area of the Hanford Site,” said Ike White, the senior adviser for the DOE Office of Environmental Management.

Rep. Dan Newhouse, R-Wash., responded to the announcement, pointing out that federal law requires the two federal departments signing the agreement to expand public access to the top of the mountain, the most prominent natural landmark in the Tri-Cities region.

“This new shared commitment by both agencies and the tribes must consider the legal requirement for responsible public access while further preserving the sacred site,” he said Wednesday.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., called the federal government’s announcement an important step in the right direction.

Acknowledging and empowering Columbia Basin tribes as partners in co-stewardship of the site sacred to them is long overdue, she said.

“The federal government must collaborate closely with Tribes on co-management plans, educate the public on its full history and incorporate Tribal knowledge in its stewardship,” she said.

In 1943 the top and north face of Rattlesnake Mountain, the highest point in the Tri-Cities area, was included in the newly formed Hanford nuclear reservation, and tribes and settlers were forced to leave the land.

The nuclear site in Eastern Washington produced nearly two-thirds of the plutonium for the nation’s nuclear weapons program from World War II through the Cold War.

Rattlesnake Mountain sacred to tribes

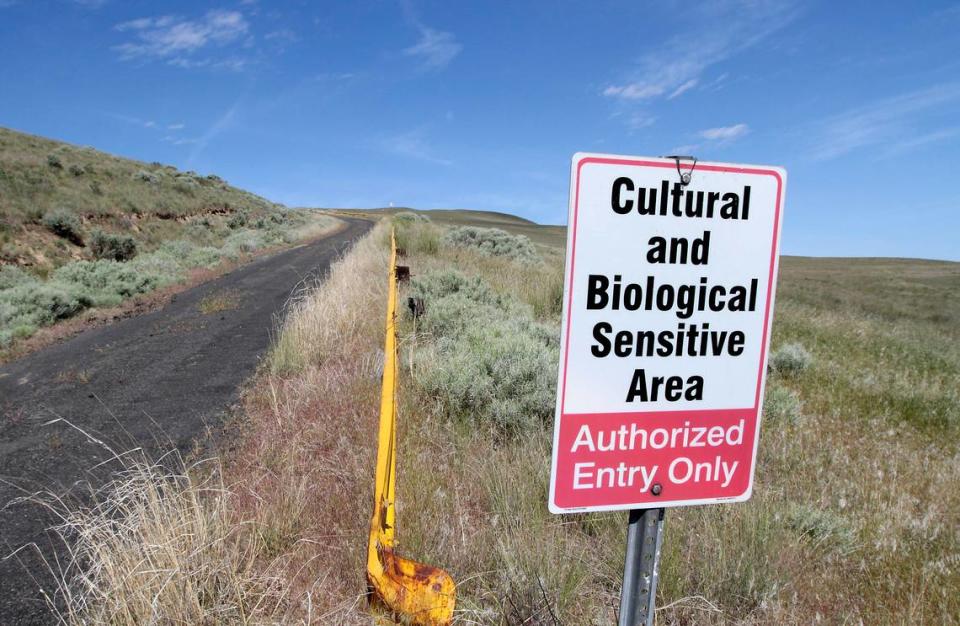

Rattlesnake Mountain, including its 3,600-foot peak, has remained relatively untouched for 80 years, after it was used as part of a security buffer around the production portion of the nuclear reservation.

It is considered a sacred site for the Yakama Nation and other Northwest tribes. They have treaty rights that provide access to the mountain, including for religious activities.

Area tribes would prefer no public access, and in 2015 the Yakamas and Umatillas won a federal ruling that the Fish and Wildlife Service must consult with tribes before conducting tours on the mountain.

In 2014, Rep. Doc Hasting, R-Wash., passed legislation as one of his last acts before retiring that requires some form of public access on the portion of the mountain owned by DOE and managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the Hanford Reach National Monument.

Some limited, small guided tours would satisfy the requirement.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, part of the Department of Interior, produced a draft environmental study on allowing limited access to Rattlesnake Mountain.

A preferred alternative called for guided tours on small buses up to 20 days of the year and hikers to climb the steep, winding 9-mile road to the top of the mountain on two days a year.

No final study was issued as talks between the federal government and tribes and Washington state historic preservation officials continued for years.

The last guided public tour of Rattlesnake Mountain, which used minibuses, was more than eight years ago, and the road to the top of the mountain remains closed with a locked gate.

In 2020, Newhouse, Hastings’ successor, and Tri-Cities leaders sent letters to Fish and Wildlife Service leaders urging them to make a decision on public access.

Newhouse said then that “everyone in our community — as well as those across the country and the globe — should have the same opportunity to experience this natural treasure right here in Central Washington.”

MOU with tribes

The memorandum of understanding recently signed by federal officials calls for an interagency team to be formed for discussions with leaders of the Wanapum Band and the Yakama, Nez Perce and Umatilla Tribes.

Discussions would include the potential for additional protective measures, improved access for tribal members and opportunities for tribes to take a more active role in stewardship of the mountain, according to DOE. It would also allow traditional ecological knowledge of indigenous communities to be incorporated into management plans.

Native Americans historically used the mountain and now periodically spend time there for religious and other traditional uses, including vision quests for young adults.

On a clear day visitors to the treeless mountain top can see Mount Hood to the southwest and across Hanford to the north to the White Bluffs along the Columbia River.

Rattlesnake Mountain is eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places as a traditional cultural property under the National Historic Preservation Act.

The objectives of the new memorandum of understanding are to treat Laliik as a sacred site and to support tribal connections to the mountain “that are essential to their spiritual interconnectedness, traditional gathering practices, and other ceremonial and cultural needs,” the agreement said.

It was signed by Jennifer Granholm, Energy secretary, on Nov. 30 and Deb Haaland, the secretary of the Interior and the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, on Dec. 1. She is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna.

It was among actions announced as President Biden held the White House Tribal Nations Summit in Washington, D.C., this week.