Feds shut down Missouri Christian nonprofit that was supposed to cover medical bills

A Missouri woman’s heart attack cost her $45,000 in medical bills. A Georgia man’s kidney stone treatment carried a $67,000 tab. A California woman was treated for a stroke and got a bill for $125,000.

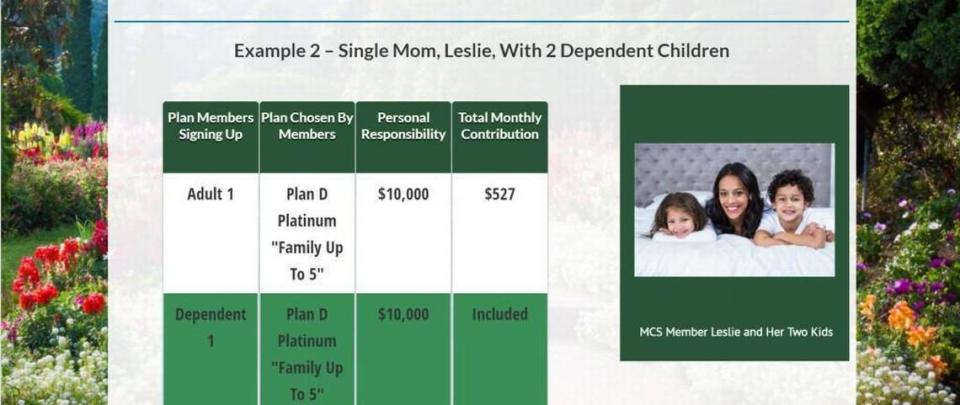

All were depending on St. Joseph, Missouri-based nonprofit Medical Cost Sharing Inc. to pay the bulk of those costs. They were members, some paying monthly premiums upward of $750 per month, of a so-called healthcare sharing ministry. Such groups are essentially charities in which members united by religious beliefs agree to help each other cover unexpected medical expenses.

But, according to the FBI and attorneys for the Department of Justice, they were all victims of an elaborate fraud scheme that spanned the better part of a decade, reeled in with a sales pitch targeting “like-minded Christians.” And all the while, the authorities allege, the two men who started the nonprofit were motivated by self-enrichment.

Complaints against the group have been public for years — The Star reported in August 2017 that at least eight people said they had paid into the fund without receiving a dime for their medical treatments. Several of them had made complaints with then-Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley’s office, which said it was mediating between the organization and consumers.

But now, federal officials have closed down the organization as they have gathered information they say amounts to evidence of years of widespread fraud. And they have seized assets of the founders, namely their homes, saying the properties were the fruits of a wire fraud and money laundering conspiracy.

Among those who submitted formal complaints was Texas pastor Jeff Gore, who paid some $4,000 in membership fees into the fund but never received compensation for care.

“It’s ridiculous. I mean, it’s been five or six years now, and the feds are just now getting involved?” he told The Star during a recent phone interview. “I was not the first complaint. The Better Business Bureau had a file opened up already. The attorney general already had a file on these people when I contacted them.”

Since its creation in 2013, Medical Cost Sharing has — by the government’s estimates, based on access to its financial records — collected roughly $7.5 million in membership fees from members around the country. But over that time, an estimated $246,000 — or 3.5% of money collected — actually went toward sharing the cost of health care bills, according to government estimates.

While advertising its services through Christian-affiliated radio and social media, the federal government says, Medical Cost Sharing has engaged in a pattern of denying legitimate medical claims “based on a variety of specious reasons.”

Instead, founders James L. McGinnis and Craig A. Reynolds, both of St. Joseph, allegedly spent much of the charity’s money on a variety of things not related to health care. And they put at least $4 million into their own bank accounts, the federal government says — allegedly taking far greater compensation than was listed on the documents they submitted to the IRS on tax forms.

Reynolds was an insurance broker licensed to work in both Kansas and Missouri prior to the creation of Medical Cost Sharing. But in 2009, his license was revoked in both states amid allegations that he forged signatures on insurance applications.

McGinnis previously held a Missouri insurance license, but it expired in 2018. There is no record of an enforcement action against him listed by the Missouri Department of Insurance.

In early December, the FBI and IRS raided the homes of McGinnis and Reynolds along with an office space in St. Joseph in search of evidence to bolster their case alleging a wire fraud conspiracy built on empty promises and gross misrepresentations. Both homes were also seized under civil forfeiture law as they were allegedly the fruits of wire fraud and money laundering.

Neither McGinnis nor Reynolds has been criminally charged. They have retained the counsel of the Hensley Law Office, a Raymore firm that specializes in criminal defense.

Asked to address the government’s allegations, lawyers did not respond to The Star’s requests for comment. In a formal answer to the allegations, filed Feb. 3 in the Western District of Missouri, the defendants denied that McGinnis, Reynolds or Medical Cost Sharing were committing fraud.

But the allegations were enough for District Judge Greg Kays to issue a preliminary injunction against the charity.

In an order filed in January, Kays found sufficient probable cause of “ongoing fraudulent conduct in violation of the wire fraud statute.” His order effectively stopped Medical Cost Sharing from doing any business, including maintaining its website, until further notice.

The organization was further ordered to keep all records related to its business, stop enrolling members to the program or soliciting others, and prohibited from taking any money from its current members.

After the landmark Affordable Care Act — commonly known as Obamacare — was passed, healthcare premiums increased for most Americans as insurers were required to cover certain preventative care and not discriminate against pre-existing conditions.

The law, though, contained a carve-out for health-care sharing ministries, which were explicitly exempt from ACA requirements, allowing them to offer monthly dues lower than typical insurance premiums, especially for people who accept less coverage and more personal risk.

It also exempted members of those ministries from tax penalties imposed on the uninsured as an incentive to get insurance. While the organizations can provide coverage for major expenses, they don’t face the same regulations as traditional insurers.

During its investigation of MCS, the FBI spoke to at least seven people — four from Missouri, three others from Georgia, California and Texas — who claimed they were duped by the charity and wound up with major health care bills as a result.

They signed up for plans that they said promised to cover all pre-existing conditions in exchange for monthly membership fees, like premiums. But when they complained about astronomical charges from hospitals, they said, Medical Cost Sharing told them the members were responsible for negotiating with hospitals and accused them of not being truthful about their health history.

For example, the Georgia man who sought kidney stone treatment at the hospital did so one day after waking with severe back pain. Through a family plan, at $784 per month with a $1,000 “personal responsibility,” he and his wife had contributed nearly $12,000 to the health-sharing ministry by that time.

Eight months later, when the $67,000-bill came in the mail from the medical provider, he says MCS denied they would “share” the cost because he had a “pre-existing condition” of a kidney stone from 12 years earlier.

In other cases: Two women, one in Missouri and another in Texas, gave birth to children in 2020 with the expectation that MCS would share hospital costs associated with the deliveries. But they were denied based on a finding by MCS that their pregnancies were pre-existing conditions to membership.

Of the seven interviewed by the FBI, some reported receiving partial breaks from the hospitals on their bills after negotiating with the health care providers themselves . A few said they received some type of restitution after pursuing consumer complaints with the offices of state attorneys general or hiring private attorneys — but all wound up short-changed, according to the FBI.

The Missouri woman who had the heart attack, and previously was enrolled in an MCS “Platinum” plan at $233 per month, still owes health care providers $36,000 and is on a scheduled repayment plan of $533 monthly.

At least four of those interviewed by the FBI filed complaints with the Missouri attorney general’s office dating back to 2018, a year after the office had already been investigating several other complaints.

The Star asked the attorney general’s office to provide details of its investigations into MCS, including the total number of complaints made and actions taken against the charity since the creation of MCS in 2013. The office would not answer specific questions, but said it is still in active mediation between consumers and MCS, though some complaints have been resolved over the years.

“We encourage any Missouri consumers who feel they’ve been defrauded by this company to reach out to our office and we’d be happy to look into their specific complaints,” said Madeline Sieren, spokeswoman for Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey.

Gore, the Texas minister featured in The Star’s 2017 story, said he has not been involved in the federal government’s investigation into MCS.

Several years ago, he ended up in a doctor’s office. After an MRI, he was diagnosed with a torn meniscus. Despite paying for about five months of MCS membership fees, he said the organization never paid either of the medical providers.

“I wanted them to pay me my premiums back because they were fraudulent,” said Gore, who is now 60. “It was a scam.”

Gore was lured by the pictures of crosses, praying hands and Bible verses that dotted nearly every page of the Medical Cost Sharing website. A “cowboy minister” who travels to rural churches preaching the Gospel and playing music, Gore liked what he saw and signed up. “Their website said all the right things,” he told The Star in 2017.

After going through the attorney general’s mediation process, the organization ended up paying his medical expenses.

He’s glad the federal government has shut the organization down, but is frustrated that it stayed open for so many years.

“I think the fact that the scam is over is good,” he said. “I wish they’d go to jail and a lot of that money could be recouped for the people who spent it…White collar crime never seems to get the book thrown at it. If they’d have punched somebody in the face in a bar they’d probably get more time.”

Gore and his wife have been uninsured for years. He said they can’t afford traditional health insurance and their experience with MCS spooked them from joining other healthcare sharing ministries.

“They’re not regulated by the government the same way insurance companies are. So they can do about whatever they want to do, they can write their own rules and regulations and make it be whatever they want it to be,” he said. “You can make a ton of money off of people paying you for insurance if you’re not ever going to cover anything.

“It was such a frustrating time. And then besides that, you just get embarrassed. Like, how can I be so stupid and gullible, you know?”