We have a right to feed the homeless | Opinion

When we arrive at the park each Saturday afternoon with pots of aromatic black beans and rice, lentil and pea soup, hardboiled eggs, desserts and whatever else one of our crew has cooked up for the occasion, the people are already waiting. Some have been waiting all day, and the reason is as basic as it gets. They’re hungry. Very, very hungry.

Some haven’t had a meal since their Friday breakfast at St. Ann Place, a local homeless service provider which is closed on the weekend. In fact, the only food available to homeless folk on the weekend is whatvarious and sundry good Samaritans bring to them.

Absent these acts of kindness and compassion, driven by raw human feeling, rooted in faith or, as the case is with our Food Not Bombs chapter, disgust with a system more committed to maintaining the machinery of war than with providing for the most basic of human needs, people would literally starve.

More: As rents soar and COVID persists, more older people experience homelessness in Palm Beach County

So it is with more than a little anger that we take the city’s effort to stop what our collective conscience dictates we have to do, and will continue to do despite their criminalization of decency.

Last Saturday, Aug. 26, three of our group’s members were issued citations in Nancy Graham Centennial Square for violating West Palm Beach’s ‘large group feeding’ ordinance, which the citycommission unanimously approved on March 20.

The law mandates that anyone hosting a special event in which food is shared involving 25 people or more – including those doling it out – must apply for a permit 30 days ahead of time. Of course it’s the citythat decides whether or not to issue that permit, the fee for which is $50. It gets worse.

Not only must this permission to feed hungry people be granted by the powers-that-be before the ladle gets dipped in the soup but the ordinance sets a limit of two permits per location per year. And aye, there’s the rub, for that would be the death of FNB West Palm Beach and end 16 years of sharing wholesome vegan meals with folks who both need the sustenance and appreciate every morsel.

We’ve seen this script before. Nine years ago, some may recall, the City of Fort Lauderdale passed a food sharing restriction which led to multiple arrests of members of that city’s FNB chapter, who in turnsued the city for violating their First Amendment right to promote the group’s anti-war agenda while sharing a weekly meal in Stranahan Park.

More: A former supermodel tells her story of homelessness to revival in South Florida

After a lengthy legal battle that saw the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit twice overturn a district court ruling that sided with the city, the food sharers won. The appellate court opined that the group wasengaging in First Amendment-protected “expressive conduct.” Just like we’re doing in West Palm Beach.

We also can’t forget the city’s passage of a panhandling ordinance in late 2020 despite warnings from a multitude of civil rights lawyers, including the ACLU of Florida, that the proposal was unconstitutionalbased on a sound legal precedent. The city was sued and, after paying damages to three plaintiffs and legal fees, repealed the law within a year.

Mind if I dish out another food reference? We relish our day in court.

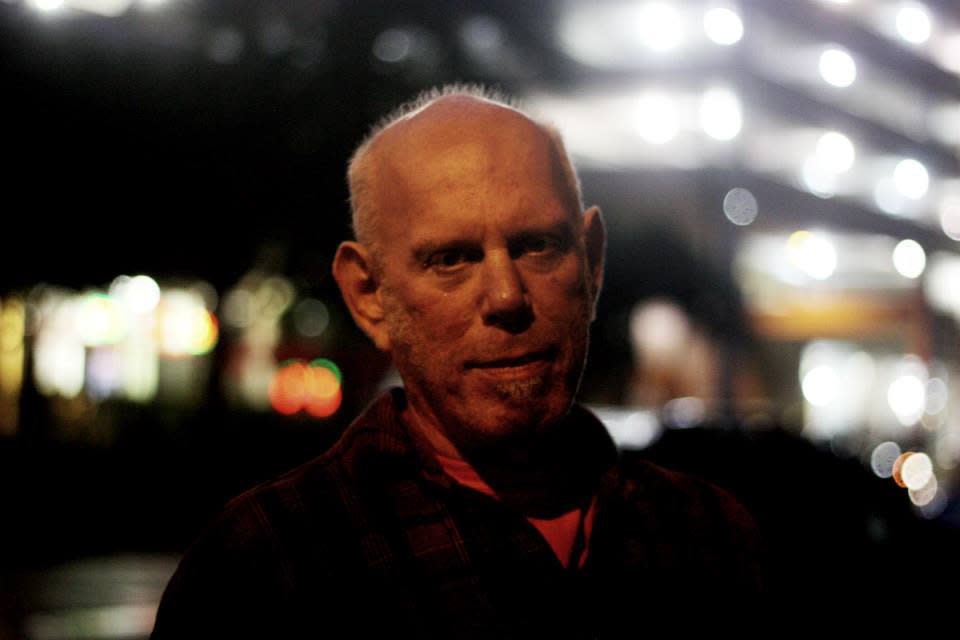

Jeff Weinberger is a member of Food Not Bombs West Palm Beach.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Group members fined for feeding West Palm Beach homeless