'Emotional torture': Austin woman's story of a doomed pregnancy amid abortion ban

When Taylor Edwards learned that her unborn girl, Phoebe — her first pregnancy, one she had gone through two years of fertility treatments and hundreds of painful injections to conceive — was going to die, it was "the worst moment of my entire life," she said.

Edwards learned of Phoebe's fatal fetal diagnosis on Feb. 20 — her and her husband’s eighth wedding anniversary.

A maternal-fetal medicine specialist told the couple that Phoebe had encephalocele, a rare neural tube defect that causes brain tissue to protrude out of the skull. While a small percentage of fetuses with the condition — about 10% — survive, Phoebe wasn't going to make it, the doctor said.

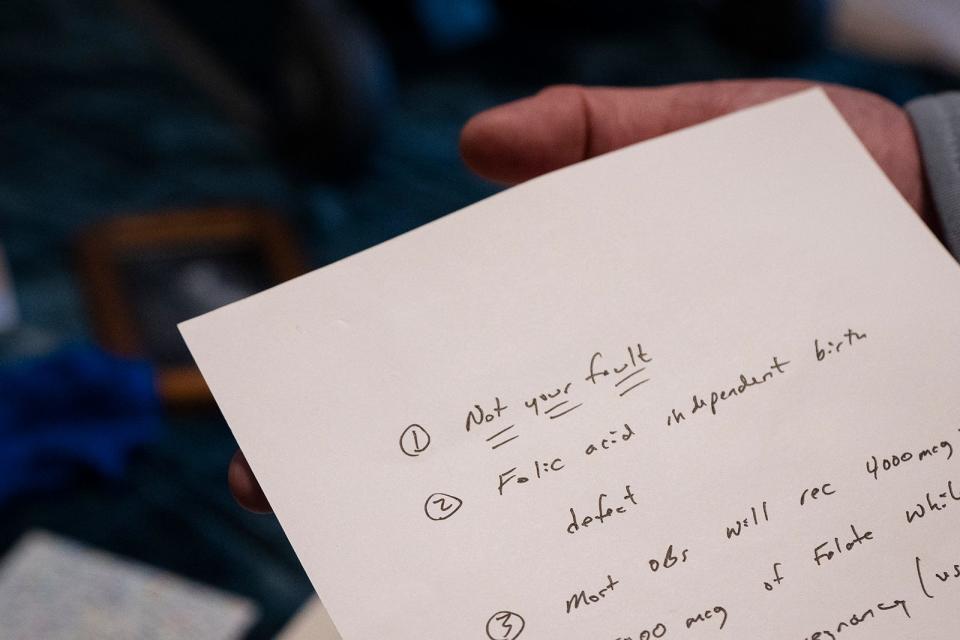

Standing in the room they hope to turn into a nursery, her husband pulls out the note they received that day. Below the hospital’s official letterhead is the name of an abortion clinic in New Mexico, written in a doctor's quick scrawl. He couldn’t help them in Texas, he said, where the procedure is completely banned except when the life of the mother is at risk.

That was the second gut punch.

The couple still hoped the baby would live, even if disabled, so they sought a second opinion from another physician. That doctor confirmed the catastrophic prognosis.

Reviewing the findings, their OB-GYN explained that the baby would never take a breath of its own.

If Edwards continued the pregnancy, the couple could lose their chance to have a living child, doctors told them.

Edwards has polycystic ovarian syndrome, a condition in which painful cysts develop on the ovaries, affecting fertility. The couple had conceived Phoebe on their third round of in vitro fertilization. Each round took several months and more than 100 injections, sometimes as many as four per day.

With the fetus having a high chance of dying in utero, Edwards would be at risk of developing sepsis, a life-threatening medical condition. She also faced all the potential dangers of a normal pregnancy, including preeclampsia, preterm labor, injury in labor or cesarean section.

"We had struggled with fertility problems for years," Edwards' husband, Travis, said. "So adding any additional risk (for) a pregnancy that we know is not viable … we couldn't risk her future fertility and her uterus health."

Riddled with grief and sadness, the couple began looking for treatment elsewhere.

'Politicians shouldn't be drawing the hard line'

Since the GOP-led Texas Legislature and Republican Gov. Greg Abbott began peeling back abortion rights in 2021 — first banning the procedure after six weeks of pregnancy and then almost entirely — the situation in which Taylor Edwards found herself is becoming more common.

She is one of a growing group of Texas women who are unable to terminate their pregnancies in the state, despite carrying fatally ill fetuses and facing serious health risks.

That group gained its most prominent member just two weeks ago, when Kate Cox became the first adult to ask for a court-approved abortion in more than five decades.

The Edwardses watched in horror as Cox's Dec. 7 court-approved abortion was appealed by Attorney General Ken Paxton and then denied by the Texas Supreme Court on Monday. Like Edwards, Cox was carrying a fetus with a fatal diagnosis — trisomy 18, in Cox's case — and faced potential loss of fertility. And like Taylor Edwards, Cox was eventually forced to leave the state to end her pregnancy.

Edwards also knows what it’s like to face off against Paxton and the state in court.

She is among 22 plaintiffs in another case before the Texas Supreme Court — Zurawski v. Texas — that challenges the state’s enforcement of its abortion bans. In a hearing at the Court on Nov. 28, attorneys for the Center for Reproductive Rights argued that the state's lack of guidance on enforcing Texas' abortion bans have caused and will cause irreparable damage to women who need emergency abortions. It also argues that the laws are unconstitutional.

Edwards has found solidarity with other women in the Zurawski suit, including fellow Austin resident Kaitlyn Kash.

Kash and her husband received a devastating fetal diagnosis at 13 weeks pregnant and left the state to seek care in the fall of 2021.

The state has argued that its abortion laws are clear and that doctors are solely responsible for the negative outcomes the women have described. In a Travis County District Court hearing in July, a state solicitor drove home the point by asking each of the plaintiffs, "Did Ken Paxton tell you you couldn't get an abortion?"

"Ken Paxton told Kate Cox she couldn't have an abortion," Edwards said. "I don't know what else they want from us."

She believes the trial revealed the state's awareness of its abortion bans' effect on pregnant people, and its unwillingness to act on it.

"It has been infuriating to watch this happen again," Edwards said, "and to have the state show that this is what their intention is and they know what they're doing, and they never intended for exceptions to actually exist."

"Politicians shouldn't be drawing the hard line," Travis Edwards said.

Read more: 20 women and 2 OB-GYNs sue Texas over state abortion ban enforcement

'In Texas, your doctors can't help you'

Taylor Edwards doesn't know whether it was the stress of planning a major medical operation out of state or the dying baby she was carrying that caused her to become violently ill during the two weeks following the diagnosis, vomiting so constantly she couldn't keep food down.

"In Texas, your doctors can't help you," she said. "I was just alone, researching online, without any sort of guidance from anybody."

For Edwards, one of the worst parts was the uncertainty about the state's laws and the pressure the couple felt to keep their plans secret. She imagined her husband being arrested; she imagined the two of them being handcuffed as they stepped off of the plane in Texas.

It was "emotional torture," she says.

"It's already a very traumatic situation that you're put in, and to add what they intend to do with these laws — scare, and shame, and all — on top of getting the worst news in your life, it's just adding insult to injury," she said. "It's a level of emotional torture."

Scheduling issues compounded the stress. Their appointment in New Mexico was canceled three hours before their plane was set to take off, forcing them to pivot and start the process over again.

By the time Edwards was able to terminate her pregnancy in Colorado in March, she was 19 weeks pregnant, and the abortion had gone from a one-day procedure to a two-day one, with costs including travel topping $6,000.

She was so scarred that she had to have an operative hysteroscopy afterward to repair her uterus. Her doctor said the additional two weeks of fetal growth increased the damage.

Edwards said her experience and that of other women, like Cox, show the state's abortion bans are preventing people from receiving necessary medical care.

"I think Republicans in general have fallen back on 'exceptions work' and 'people, if they need medical care, they'll get medical care,'" Edwards said. "No, they obviously won't."

'I feel like I have no rights'

Beyond the physical scars Edwards bears, both she and her husband are dealing with the emotional effects of their experience.

Throughout the couple's home in Austin, there are reminders of who they lost eight months ago: a Christmas stocking hanging next to theirs on the fireplace; a necklace with gems spelling out "Phoebe" that Taylor Edwards wears each day; a box of doctors' notes, ultrasound scans and sympathy cards.

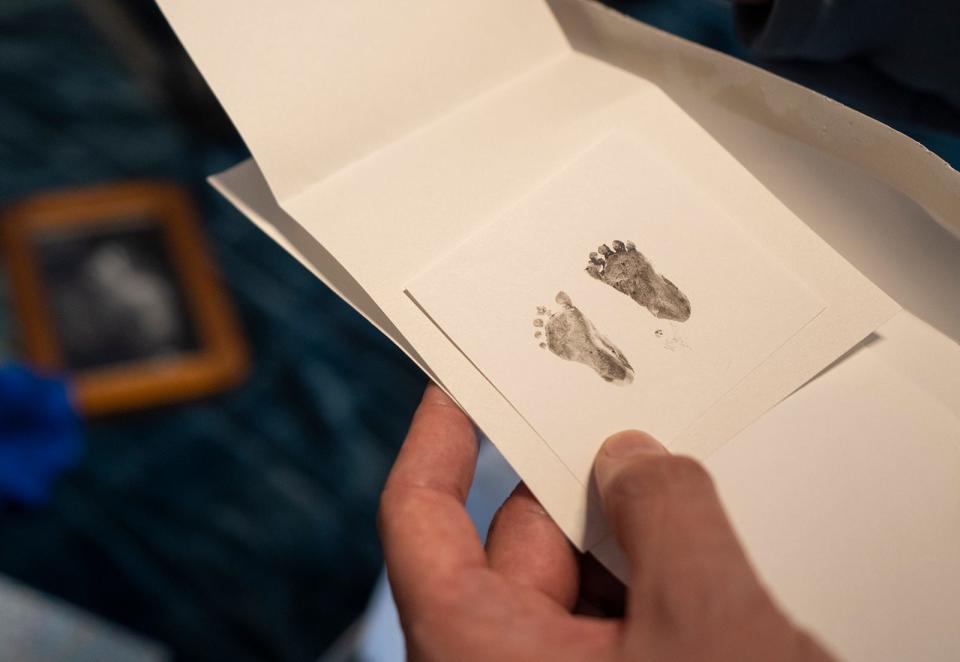

But all they have left of their unborn baby are two tiny ink footprints on a piece of cardstock, made by staffers at the abortion clinic in Colorado. A larger copy is framed in their living room.

"I wish we had more," Edwards says as her husband shows the card. "I wish we had ashes."

Details such as arranging for cremation got lost in the scramble to make travel plans before Edwards faced further pregnancy complications.

Had they been able to have the procedure in Austin, the couple would have had their parents by their side and their friends ready to console them over the death of an expected and already deeply loved family member. They could have gone home to their beds instead of an empty hotel room. They wouldn't have had to spend so much time in public while going through "the worst thing that has ever happened" to them.

While they honor Phoebe's memory, the couple have also set their minds to the future: Taylor is 22 weeks pregnant with a baby boy. The couple are terrified that something else could go wrong but remain cautiously optimistic, slowly turning their guest bedroom into a nursery and buying books and toys.

"I feel very lucky to be pregnant," Taylor said. But "as a pregnant woman, I feel like I have no rights."

The couple have also turned their grief into action as they share their story, hoping to educate others and offering support to those affected. This work has been empowering, Taylor said, and has helped her feel comfortable continuing to live in her home state.

"When you live somewhere and you're told that you don't have rights, it's really tough," she said. "But I want to stay in Texas and fight. I'm willing to stay here and fight as long as necessary."

Have you or a partner gone through a difficult pregnancy in Texas recently? The American-Statesman wants to hear from you for future coverage. Get in touch via email at bwagner@statesman.com.

Read more: Here's what the Texas Supreme Court's ruling against Kate Cox means for abortions

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Austin, Texas woman's story of a nonviable pregnancy amid abortion ban