After felony conviction and 5-year fishing ban, the Caviar King returns to the Ohio River

David Cox is 69 years old. Emphysema makes every breath a challenge. Doctors have put so many stents in his heart that he’s lost count. And he hobbles on a bum leg overdue for surgery.

None of that, though, keeps him from fishing.

But Cox isn’t a run-of-the-mill angler.

A long-time commercial fisherman, Cox was — and, at least in his mind, still is — Indiana's de facto Caviar King.

He's backed up the self-proclaimed title with more than three decades of hard work, a deep knowledge of the Ohio River, and a big mouth. Since 1999, Cox and his family have caught and processed more than 15 tons of caviar worth millions of dollars. The black gold was pulled from the cold, unforgiving river one large American paddlefish at a time.

The caviar business has been lucrative and fulfilling for the Hoosier who grew up hunting and fishing. It’s also taken a toll, heaping stress on his body and family. The pursuit ultimately landed Cox in federal prison for two years after he was snagged in an undercover sting. He wound up with federal convictions for keeping an undersized paddlefish and illegally possessing guns as a felon.

Indiana caviar?: Here are 7 thing you probably didn't know about paddlefish and Indiana's caviar industry

Even after Cox's release in 2020, the sentence banned him from commercial fishing for another three years.

When the court-ordered prohibition expired in March, Cox was back on the river in his 24-foot Alweld boat loaded with nets and floats. After more than five years away, he planned to ease back into fishing for the final weeks of the paddlefish season that ended April 30.

The trial run didn’t go as he hoped. Other fishermen, including some Cox mentored, had jumped on “his” honey holes. He had trouble finding reliable help with the physically demanding work. And while his head and heart were still into it, he wasn’t sure his body could take the grind of a full season. More than once, Cox said he was on the verge of calling it quits.

Six months later, though, Cox said he’s recharged and ready to get back to "feee-shun" when the season opens Nov. 1.

He still has concerns about making it through another hard winter on the river, but can’t get away from the chase. It was a fate his future father-in-law predicted when Cox got his first taste of commercial fishing. A barefoot 16-year-old Cox had just jumped in the boat.

“He told me, ‘Look at your feet. You’ve got mud between your toes. You’ll never wash it out,’” Cox said, pausing to look down and shake his head.

“I’m still trying to wash it out.”

'Shut up and fish'

Indiana’s unlikely tie to caviar is one of those little-known stories that makes you go wow. Who knew the landlocked Crossroads of America had a multi-million-dollar cottage industry that took off in the 1990s on the Ohio River to fill a void in the international caviar market?

The handful of fishermen who keep the industry alive go about their work almost entirely out of the public eye. That anonymity ended for Cox when he was sent to prison in 2018. For him, it was just another chapter in a colorful backstory that reads like a mash up of Huck Finn, Robin Hood and the Tiger King.

On a cold, windy day in mid-April, Cox backed down a boat ramp at Troy, a small river town about five miles northwest of Tell City. The water was running high and the slick layer of mud coating the parking lot showed it had been even higher in the preceding days.

With his boat in the water, Cox stood beside his truck and slipped on cold-weather gear and waders. Before casting off, he walked over to a group of boys fishing near the ramp. Cox had given one of them some fish from his catch the day before and wanted to know if anything was biting. Then he and two helpers clambered into the boat, fired up the 115 horsepower Yamaha motor and bounced downriver.

Painted on the console of Cox’s boat is an admonition: "Shut up and fish." As Cox headed off to check nets he’d put in the water the previous afternoon, choppy waves splashed him and his helpers with cold, muddy spray. No one complained, but Cox broke the silence with tribute to his "office."

"You see how the leaves are starting to turn green," he said, motioning to the tree-lined riverbank. "I get to come out here when the leaves are falling off and when they’re starting again. Has anybody else got an office like this? It's paradise.”

Over the next four hours Cox and his crew hauled in net after net, each one a giant curtain of mesh dangling in the river. Gaps in the mesh allow smaller fish to pass through while snagging the big ones Cox wants. It's the only way to catch paddlefish, which are filter feeders who typically don't bite on baited hooks or lures.

The first few nets came up empty, or with no paddlefish longer than the 32-inch minimum. Steering the boat near an eddy along the Kentucky shore, Cox explained the place was one of his reliable spots for years but had been claimed by interlopers while he was gone. He chalked it up to a loss of the respect that existed among the loose-knit brotherhood of commercial fishermen when he started in the early 1970s. Now, he said, it's all about money.

Cox's mood rebounded as he moved down the river and his crew landed several legal-sized female paddlefish before heading back to the boat ramp.

More than fishing and feuding

At the crest of a hill on Indiana 64, just west of the small Southern Indiana town of English, a single-engine airplane appears to be nose-diving into the highway. The pole-mounted plane is surrounded by metal palm trees, brightly colored tin flowers and assorted whirligigs crowded together behind a tall chain-link fence.

The gewgaws hype some of the items for sale at Midwest Antiques and Collectibles, the shop Cox and his wife, Vicki, have operated since 2008.

The plane tells a different story. “CAVIAR KING” is painted on the doors. But the series of letters and numbers on the plane's side aren't on the FAA registry. For that, you’ll need to check another federal database: The Bureau of Prison’s inmate roster reveals it was Cox’s identity as a federal prisoner. The fact he unabashedly flaunts it now says a lot.

Cox is a brash open book, with a subtle sense of humor, a flair for getting attention, and a healthy dose of disdain for authority. He's more likely to describe the prison-number joke, with a slow Hoosier drawl, as a middle finger to his many detractors — and it's a long list.

Spend some time with Cox, though, and it's obvious there's more to him than fishing and feuding. He's a hustler who's worked hard and sacrificed to get past every challenge he faced, from dysfunctional parents and dropping out of school to struggles with drugs and alcohol and run-ins with the law. Most of all, beneath his rough exterior, Cox is loyal to family and friends, generous to strangers who need a hand up, and a Christian at his core. Those traits are cited over and over in more than 80 letters of support in his court file. Cox says he's a giver, "probably because no one ever gave me nothing."

Since his release from prison, Cox and his wife have lived in an apartment above their Crawford County antique where they host weekly Bible study meetings. They also own a couple of acres across the road that serve as his oversized mancave and playground. There’s a small pond, chicken coop and garden, a couple of rusty old cars, and storage buildings for his boats and fishing gear.

A new addition this year is a used semi-trailer Cox converted into a stainless steel kitchen to clean fish and make caviar. The large masses of eggs are removed from the fish before the boneless meat is fileted and frozen. The precious tiny black pearls are rinsed and gently rubbed through a screen to separate them from the skein, a thin membrane that holds them together. They are rinsed and drained again and put into a large metal bowl, where a few spoons of salt is delicately incorporated. That's it. The fresh caviar is packed into small containers and put in cold storage.

The processing trailer is efficient but tiny compared to the facility Cox had before he was busted, a 12-acre compound north of English where he lived and ran his business, Midwest Caviar. He saved several signs from the old place. One is hand-painted. There are only three words but they have fueled controversy for years: “LET’S KILL FISH”

The placard hung for a decade at Cox's old processing facility. Many saw it an extension of Cox's perceived disdain for wildlife, an allegation that came up in his criminal case. Cox insists it's simply another jab at critics, who for years have blamed him for the declining number of paddlefish in the river.

To Cox the signs are reminders of the good times his family spent at the compound, even if the place ended up being the scene of arguably his darkest day.

A look back: Cincy caviar ranchers bringing indulgence to your plate

Undersized fish, guns lead to bust

The sound of people shouting his name rousted Cox from bed on May 10, 2017. Dozens of state and federal wildlife officials had surrounded his home. Several came inside. As he got dressed, two officers entered his bedroom with guns drawn. They led him to the stairs.

Cox said other officers had guns aimed at him as he slowly descended the steps and was led to the front porch. That’s when he learned what all the commotion was about. The answer started with a question: “Do you know what we’re here for?”

He didn’t get time to answer.

“They open this folder up and they show me a picture of a spoonbill a half-inch short. They had it marked and everything,” Cox said. “I said, 'you all come here for one f------- fish a half-inch short, come on man?' That’s what got them in my door.”

Cox's fate was sealed, however, by what the officers found once they got inside his home and business.

The search turned up several guns, which he was prohibited from having due to a prior felony conviction. The raid kicked off a five-year odyssey that turned Cox's life upside-down and provided an unprecedented glimpse inside the state’s caviar business.

Cox didn’t fight the charges. He pleaded guilty to the gun charge and violating the Lacey Act, a federal law intended to protect wildlife, and did his time.

Complicated childhood, first memories of fishing

Cox grew up in a middle-class neighborhood in Clarksville, across the river from Louisville, in the 1950s. His father worked in construction and his mother had a job at a plant that made oven-ready biscuits.

“When you are young you don’t always see problems in your home,” his sister wrote in a letter asking the judge sentencing Cox to be lenient. “As you get older you begin to realize things weren’t exactly right. Our dad was an alcoholic, our mom had a nervous breakdown when we were very young.”

Cox said his first memories of fishing involve outings with his father as a kid. But these were hardly Hallmark moments.

“My dad and me would go fishing every weekend. He would go so he could get drunk. And then he'd let me drive back,” Cox said. “No license. No nothing. I was just a kid.”

By the time he hit his teens, Cox was running with an older group of boys and flirting with trouble. “I skipped school all the time,” he said. “That's why I can barely read, write or do any of that.”

When he was 15, he was sent to see a psychiatrist. It didn’t help. The woman told him to leave his dysfunctional home as soon as possible. Cox quit school the day he turned 16. An aunt co-signed a loan so he could buy a used Country Squire station wagon with fake wood-grain side panels.

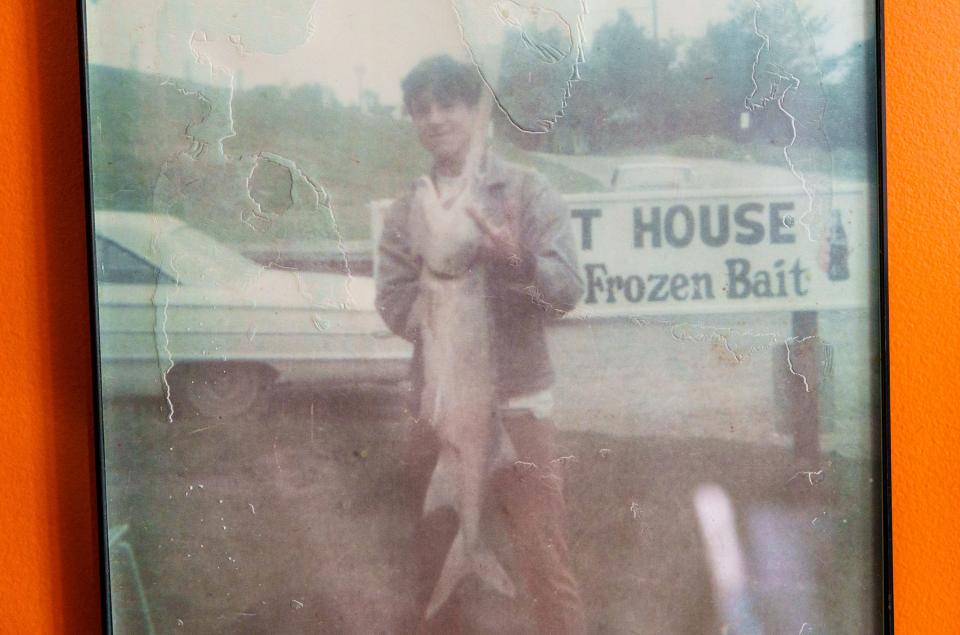

Cox loaded a few things into the car and headed into the world with no real plan other than spending time his girlfriend Vicki Burns. Her dad, Maurice “Boots” Burns, was a second-generation commercial fisherman who ran a market and bait shop on the Ohio River in Clarksville. Cox helped there and did other odd jobs, including his first stint in commercial fishing, while living out of his car parked behind the market.

In 1971, with the blessing of Vicki's parents, the two 17-year-olds drove to Tennessee and got married. Their son, David, was born in 1972. Over the next several years Cox continued to help on his father-in-law's fishing crew, while picking up construction jobs, hunting and trapping, and carousing with a rowdy group where alcohol and drugs were plentiful.

During that time, Cox and "Boots" had a serious run-in with a game warden who ended up in their boat after a mid-river tussle. They eventually returned the officer to the shore, but roughed him up and took his gun before fleeing. The incident led to a 1977 conviction for assaulting a federal wildlife officer, a felony that prohibited Cox from possessing guns.

That same year, the couple had their second child, Jessica.

Walking away from the river

Not long after the game warden incident, Cox quit commercial fishing and moved his family a few miles north to Charlestown. He opened Dave’s Old Strip Joint, where he refinished and repaired furniture for high-end antique shops in Indiana and Kentucky.

The couple relocated to English in the early 1990s and opened Close Encounter Exotics, a roadside animal park that attracted local residents, passing motorists and school groups. They also displayed some of their wild animals at car shows and community festivals.

Close Encounters Exotics made news in Indianapolis when a 9-week-old Bengal tiger cub born at the park died following an unusual emergency surgery in Indianapolis. The procedure to correct a cleft palate — a last-ditch attempt to avoid euthanizing the cub — was led by the chief of plastic surgery at Riley Hospital for Children.

The Indianapolis Star covered the quirky event. "Never has a tiger hosted such a crowd in an operating room," The Star reported. The article explained the surgery was documented by a crowd of medical professionals, hospital photographers, and newspapers and television teams.

The animal park brought Cox in contact with a network of collectors, breeders and dealers — some of whom would later gain notoriety. Tim Stark, who operated Wildlife in Need and Wildlife in Deed in Charlestown and was featured in the “Tiger King” documentary, bought his first big cat from Cox. He also sold big cats to “Roy Boy” Cooper, a flamboyant tattoo artist who used them in racy photos for calendars and videos promoting his Gary-based shop.

Cox’s growing presence in exotic animal circles put him back on the radar of federal wildlife officials. That attention led to a 1992 Lacey Act conviction after he drove to Tennessee to buy a bear in a deal that turned out to be an undercover sting.

How he became the Caviar King

Cox returned to commercial fishing in 1999, hoping to cash in on a growing demand for caviar from sources outside Eastern Europe. Over the next two decades he aggressively pursued Ohio River paddlefish, competing with a handful of other commercial fishermen. Their combined haul peaked in 2006 with a harvest of more than five tons of caviar.

The next year, Cox incorporated Midwest Caviar. His son was in the family business, which expanded to purchasing and processing roe from other fishermen. In 2009, his daughter and son-in-law started their own caviar processing operation in English. For the next few years the small town in one of the state's poorest counties was the epicenter of Indiana’s caviar industry.

The state didn’t closely track the caviar catch in the early 2000s, so it’s impossible to say how much Cox and his family caught and sold. And he’s not telling, other than it was “thousands and thousands of pounds” a year. A review of state records from 2010-2017, the period after the peak harvest years in the early 2000s, shows at least 15 tons of caviar — with a wholesale value north of $5 million — passed through the two processing plants in English on the way to New York, Florida, California, Russia and Japan.

Cox’s caviar website boasted in a 2017 post about the family's contribution to the industry: “For the past few years MIDWEST CAVIAR has caught half of the harvest reported being caught in Kentucky and Indiana.”

“It was wonderful. I could fish six months out of the year. My whole family would be, you know, everybody was fishing for me,” he said. “They was all making money. I was making money. That's what paid for everything we got … But you don't understand how hard and tough it really is. I mean, it's crazy.”

Cox's granddaughter, Lyndsie, is planning a podcast on her grandfather's escapades on the river and beyond. One story she'll likely share is about his biggest one-day catch: 54 plump “sows” full of caviar, which brought Cox $35,000. The biggest fish of the bunch yielded 17.5 pounds of roe, a haul worth more than $1,800 at the wholesale price of $175 a pound.

“When fishing was good, it was good. But it's fishing. You got bad days you got good days,” Cox explained. “Some days you might make a fortune, next day you might not make nothing for a week.”

Through all the ups and downs, the woman Cox calls "my angel" has stuck with him.

"I would have never made it without Vicki," he said. "She has been the rock to put up with all the shit I put her through. She is one of a kind."

First impressions can be misleading

Cox’s brash attitude didn’t sit well, at least initially, with many of his competitors. Even before they crossed paths on the river, Robert Housman knew all about Cox. The fisherman who splits his time on the Mississippi and Ohio rives, had heard the stories and seen pictures of Cox and his boat filled with paddlefish in advertisements and calendars.

“The first time I met him I wanted to kick his ass,” Housman said. “He’s a mouthy dude. David called the whole river his and he asked who I was and who I was selling my eggs to.”

Over time the two became more friendly and earlier this year Cox even purchased some finished caviar and paddlefish meat from Housman to help reboot Midwest Caviar. One of Cox's new customers is Andrew Caplinger, co-owner of the five Caplinger's Fresh Catch markets around Indianapolis.

Caplinger met Cox after his family bought a fish farm near English. During one trip to the farm, he stopped at Midwest Antiques looking for stuff related to catfish. He ended up talking to Vicki Cox, who told him about their commercial fishing and caviar business

Caplinger met Cox on a subsequent visit and they hit it off. Cox volunteered equipment and help with the fish farm and Caplinger bought some caviar and paddlefish meat. The items were outside what he typically sells, but he thought there was a market for them. Caplinger was pleasantly surprised by the meat, which is boneless and firm with a mild flavor. He compared it to a freshwater version of swordfish and bought about 700 pounds. It's a hard sell initially because people don't know about it, he admitted, "but once they try it, it's over."

The markets typically don't sell caviar, either, but Caplinger bought some from Cox. With a good flavor and comparatively low price, he thinks it is a great option for introducing the delicacy to his customers.

Caplinger wasn't daunted by Cox's notoriety and said he's like caviar: People either love him or they hate him.

"I'm sure there's a lot of people that probably think pretty poorly about him because of things that they've heard. But I have never had a bad interaction with him. He's got a big heart and is one of the most giving and helpful people that I've ever come across. And he's still doesn't know me that well," Caplinger said.

"I just think that regardless of what anybody would think about David, due to his past, they need to take a second look at him."

Tim Evans is IndyStar's investigations editor. Contact him at Tim.Evans@IndyStar.com

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Indiana's Caviar King overcame federal sting and prison to fish again