Fentanyl caused almost all Tri-Cities overdose deaths this year. ‘Too many people dying’

The Tri-Cities saw a record high number of fentanyl overdose deaths last year, and 2023 is shaping up to be just as deadly.

Community members are searching for solutions as the death-dealing opioid destroys more and more lives each year.

Over the past five years, total overdose deaths in Benton and Franklin counties have been declining, but the percentage attributed to fentanyl has skyrocketed.

So far this year, nearly every Tri-Cities area overdose death has been related to fentanyl.

About two dozen people in the Tri-Cities area died from overdoses in the first five months of this year.

Fentanyl is overwhelming killer

In Benton County, 17 people died from overdoses through June 1.

All but two were fentanyl related, according to data provided to the Herald by the Benton County Coroner’s Office.

That’s tracking slower than the total deaths last year, but the percent of fatal overdoses that were fentanyl-related are higher. In all, 37 out of the 43 overdose deaths in 2022 were linked to the potent drug.

In Franklin County, fentanyl overdose deaths through May were just below last year’s record high, with six who have died.

The share attributed to fentanyl is also higher in Franklin County — 5 of 6 the fatalities compared 14 of last year’s 22 overdose deaths, according to data from the Franklin County Coroner’s Office.

The previous high for both counties was in 2020 when there was a combined 46 overdose deaths.

And this year’s deaths will likely climb higher when temperatures drop this winter.

Overdose deaths are more common during periods of freezing weather, so numbers tend to spike when temperatures slip below 50 degrees, according to findings from a National Institutes of Health study.

According to the study, that’s due in part to on how opioids change the body’s ability to regulate temperatures, leaving fentanyl users who are outside in the cold in a more dangerous situation.

In Benton County, six of the 17 overdoses deaths this year occurred in January alone.

Repeating problem

Franklin County also is tracking the overdose history of those who have died this year, which showed that nearly all of the victims had a previous history of overdoses that they survived.

Ben Shearer, community risk reduction manager for Pasco Fire Department, said that while EMTs try to focus on the moment, they do sometimes recognize that they’ve helped the same person before, and it’s difficult, because it means that person hasn’t been able to get the help they need.

With all patients they try to offer extra resources for family members or the patient if they’re cognizant.

“We have two resource navigators who are great ladies who do amazing work, from aging and long-term care to addiction, they can help get those people to the (resources they need) if they desire the help. When we’re seeing the same people over and over, our responders see that as something is wrong in their life and it’s not getting fixed.”

The Pasco Fire Department is just one of many community stakeholders working to create new resources for people struggling with addiction through the Benton Franklin Behavioral Health Advisory committee.

The committee is currently in the early stages of planning a possible sobering center, and a crew of addiction and mental health specialists to accompany first responders.

Kelly Harnish, Healthy Living Manager for the Benton Franklin Health District, said that while their data lags because it’s compiled using death certificates, they are anecdotally hearing the same concerns with rising fatal fentanyl-related overdoses.

One area that is particularly concerning is that many of the overdoses seem to be taking place at home, where someone is likely using drugs alone, Harnish said.

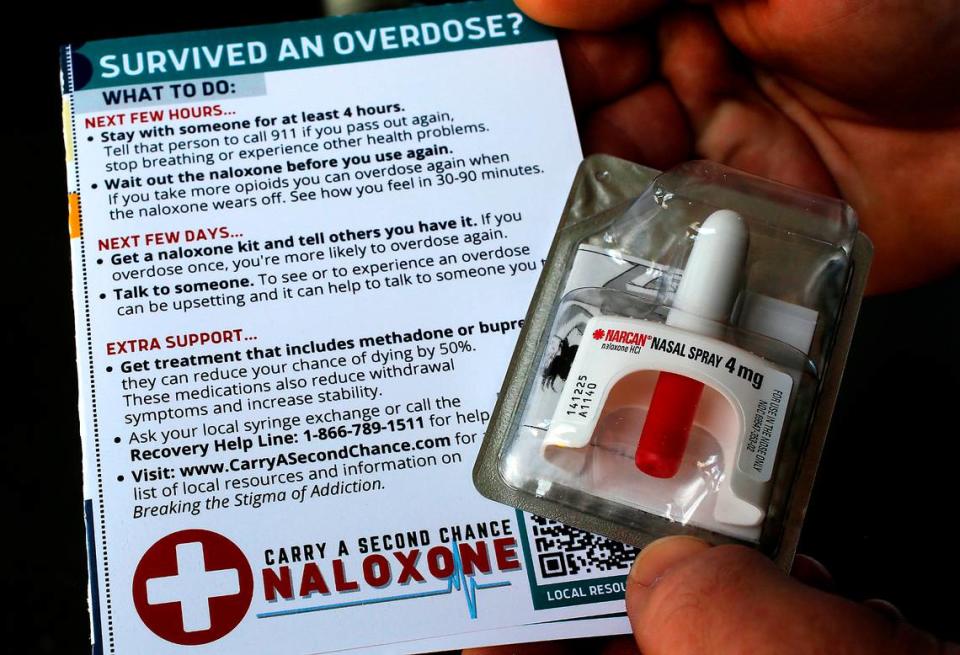

Doing so means that if they overdose, no one is around to call 911 or to administer a drug like naloxone to reverse an overdose by blocking the effects.

What’s being done

Through grant funding BFHD makes doses of naloxone, or NARCAN, nasal spray available to first responders, community partners and businesses. They’re also including tip sheets on what to do in case of an overdose with the medication.

The tip sheets explain what to do in the moment, what to look out for in the hours after an overdose and how to get long-term help.

They’ve also helped organize a local Overdose Fatality Review Board, which includes the health district, medical professionals, first responders and others who will be reviewing individual cases to figure out patterns and opportunities to respond to and prevent risky behaviors.

“Just having those in-depth case reviews will help us see what’s happening in our community, because we believe every overdose is preventable,” Harnish said.

The health department is also trying to expand a new approach to the root causes of why someone is using. They’re looking to build positive and pro-social interactions with community members in order to help build resilience.

“Another thing that we’re really trying to incorporate is the HOPE framework — healthy outcomes through positive experiences,” Harnish said. “A lot of health risk behaviors is due to early life trauma, but the antidote to trauma is positive life experiences.”

Some of the money from opioid lawsuit settlements is also set to be directed toward funding prevention and education initiatives, as well as helping pay to operate behavioral health facilities.

Fentanyl task force

The crisis has become so dire in Eastern Washington that Congressman Dan Newhouse, R-Sunnyside, recently put together a regional task force to push for change at the local, state and federal level.

The task force includes members of law enforcement, medical professionals and community members from throughout the Yakima Valley. Kennewick Police Chief Chris Guerrero represents the Tri-Cities.

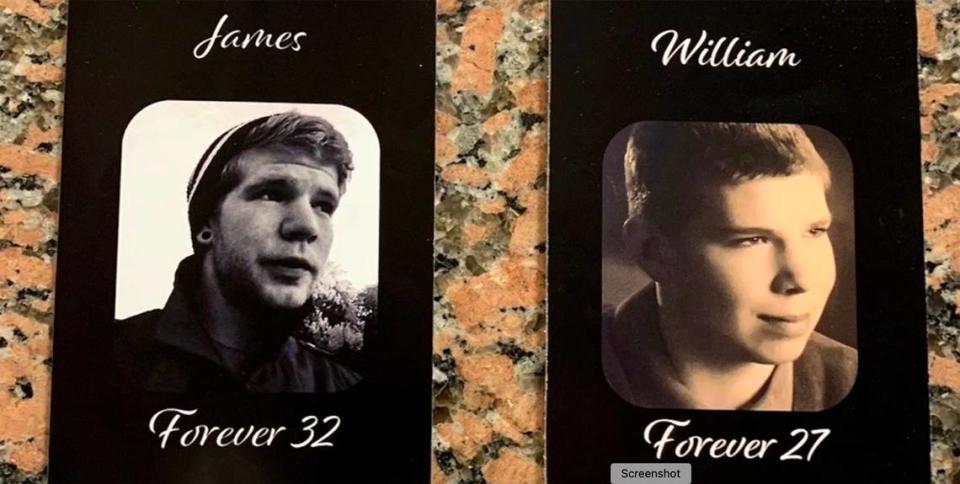

Andrew Wonacott, a community member from Yakima, told the Herald that the task force was created to save lives. Wonacott lost two sons from fentanyl overdoses within about a year and a half of each other.

Newhouse introduced the William and James Wonacott Act of 2023 in March to create harsher penalties for selling or distributing fentanyl, with a provision for more jail time if someone dies from an overdose.

Dealing fentanyl would come with a potential penalty of a minimum of 20 years in prison up to life, and 25 years minimum if someone overdoses and dies.

Wonacott has been on a mission to get officials to listen to his story and others like it — and to act.

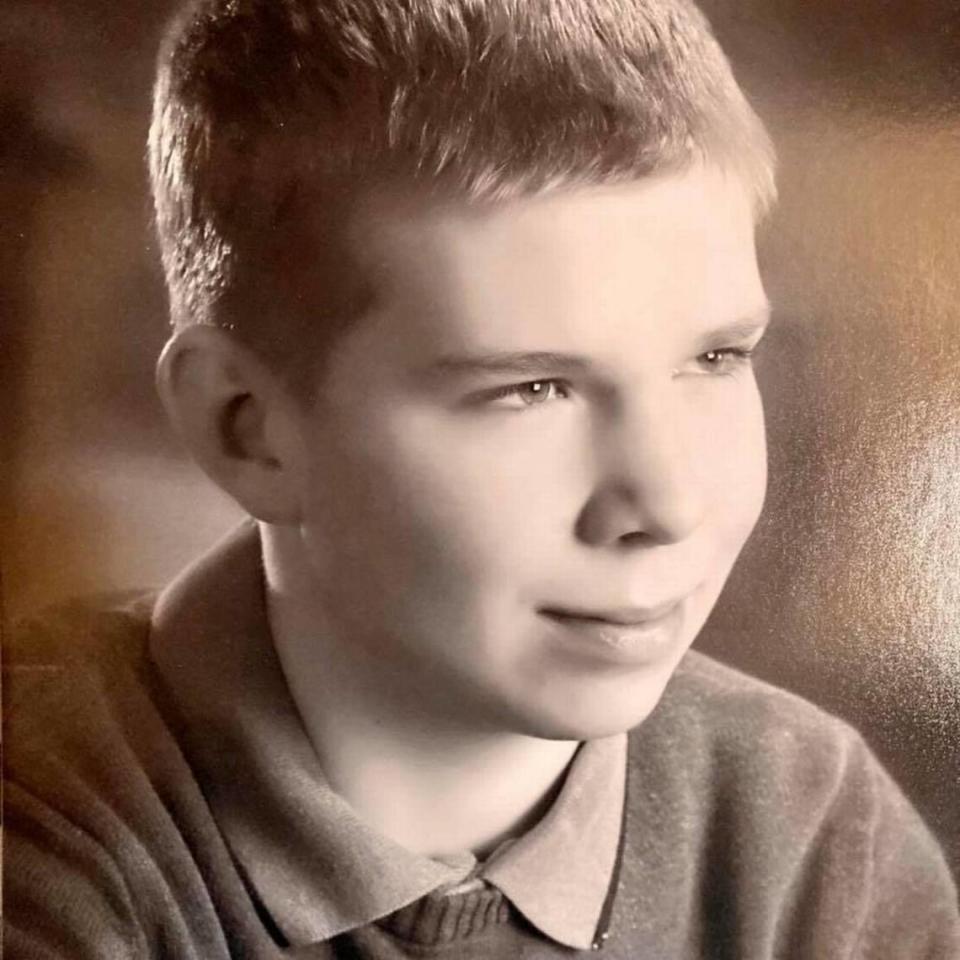

“I lost my youngest son, William, to fentanyl in April of ‘21 and that was devastating. He was in Georgia and he got some drugs laced with fentanyl and he died,” Wonacott said.

“... Then last year in November I lost another boy, James, for the same reason. That’s 50 percent of my kids gone in a couple years, that was rough,” he said.

Wonacott said that after William’s death, they tried to work with police to find the person who had sold the laced drugs, but they weren’t able to.

He said it was a traumatic experience for his family, being unable to find some kind of justice for his son’s death.

Wonacott said he reached out to Newhouse, hoping he could help. The idea for the task force came out of a town hall meeting.

“We all just had a big discussion about what we’re going to do about this because it’s terrible,” he said.

“Fentanyl, it’s indiscriminate, it doesn’t care if you’re rich, in politics or your ethnicity. It’s going to kill you and we have to do something about it. We can’t let this go by anymore, there’s just too many people dying.”

Wonacott said he won’t stop until law enforcement has the tools they need to deal with fentanyl dealers, first responders have the resources they need to help people at risk and communities prioritize real solutions.

“We’ve got to have better support systems for them, we’ve got to have real treatments that work,” he said. “My personal mission is, ‘I will not let this die,’” he told the Herald. “We have to do something, because it’s such a huge impact to all of our communities. If I can save just one person, it’ll be worth it. If we can stop the supply, it’ll be worth it.”

Accomplishing these goals will require buy in locally in individual communities and from state and federal lawmakers, he said. Wonacott knows none of these are simple solutions, but he believes if the will to make the difference is there, it can be done.

“I’m hoping that we can get some real legislation to curb the flow of fentanyl into our county and into Eastern Washington,” he said. “I’m hoping we can maybe get some real tools to impact people who are impacted by it and education for the family and community about how bad it is.”

“If fentanyl has not touched you yet, it will.”