Fentanyl devastating Akron's Black community during evolving opioid crisis

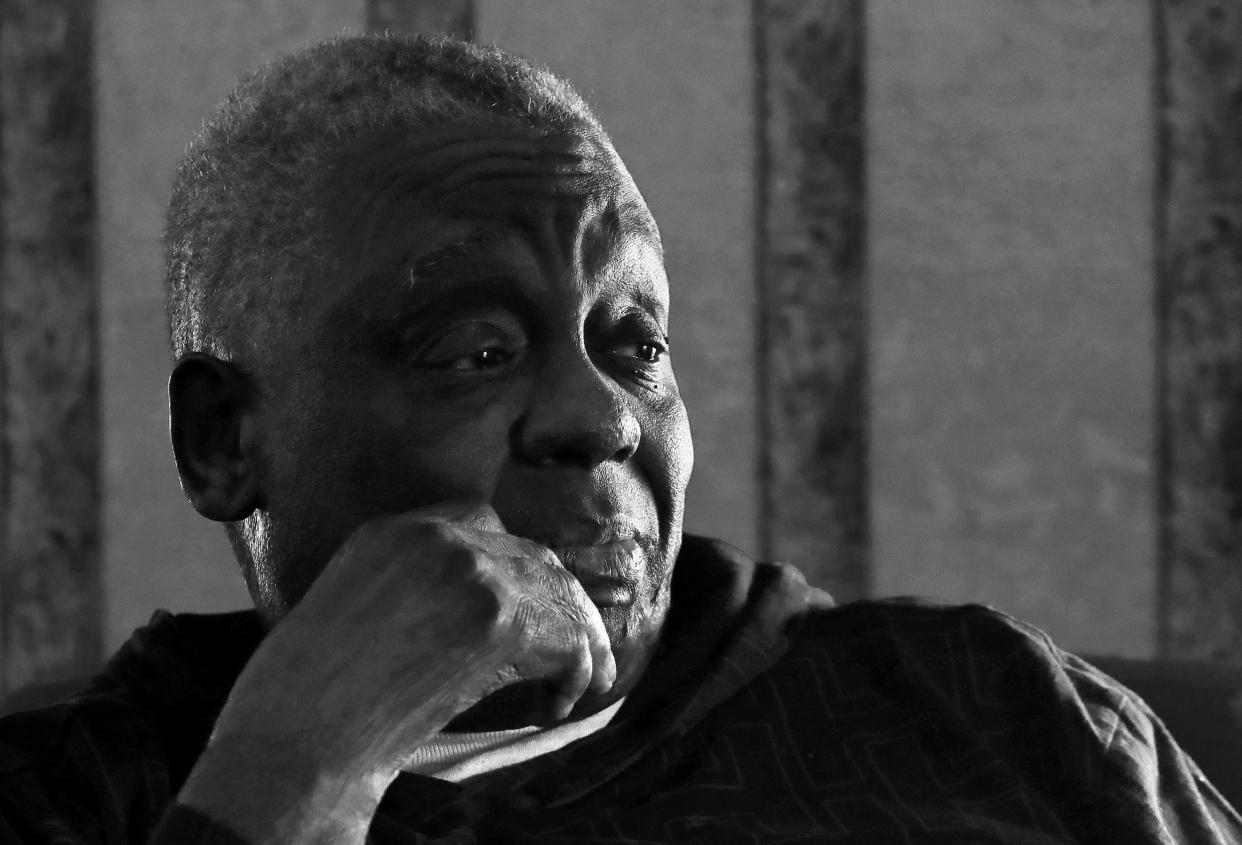

Steve Arrington’s 31-year-old great-nephew overdosed and died a couple of months ago after smoking crystal meth.

But it wasn’t the methamphetamine that killed him, Arrington said. It was fentanyl the meth was laced with.

“Fentanyl is in everything now — methamphetamine, crack-cocaine, (fake) prescription pills, even marijuana,” said Arrington, who first noticed this trend more than a year ago during his work as the executive director of Akron’s AIDS Collaborative.

Summit County health officials say the synthetic opioid has taken over all street drugs, though they’ve not documented fentanyl in marijuana. And they say they're alarmed by this phase of the ongoing opioid crisis and particularly how it is impacting the African American community.

More white people still die from drug overdoses in Summit County every year, according to the county’s Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board, or ADM.

But beginning in 2019, the death rate of Black residents started outpacing that of whites and has continued to surge higher, said Nicholas Baechel, research and quality improvement director at ADM.

In 2022, Summit County recorded 252 suspected fatal overdoses. Toxicology tests in January were still pending in about 20 cases. Of those 252 fatalities, about 75% were white people.

But that doesn’t tell the whole story in a county that is about 77% white, Baechel said.

When Baechel compared the rates of overdose deaths in Black and white communities, he saw a gap. His analysis showed that Black people in 2022 died at a rate of 71.3 per 100,000 people. During that time, whites died at a rate of 43.3 per 100,000, his analysis showed.

The disparity grew worse when Baechel looked at the differences between Black and white men. African American men in Summit County overdosed and died at a rate of 119 per 100,000, his research showed, while white men died at a rate of 63.7.

“The point I try to make is the impact on the African American community … it’s the worst that it’s ever been and even worse than it was for Caucasians in 2016,” Baechel said.

That year was a nightmare in Greater Akron.

CDC says spike in overdose deaths, widening disparities 'alarming'

Over July 4 weekend in 2017, people in Summit County began overdosing on sidewalks, in parking lots and while driving as lab officials at the medical examiner's office official scrambled to figure out what new street drug was behind the deaths.

It was carfentanil – an elephant tranquilizer 1,000 times as powerful as morphine.

Scores of people, predominantly white people who had first become addicted to prescription painkillers, unknowingly took the drug believing it was heroin, a cheaper and more widely available option to Oxycontin.

The overdose death rate for white people in Summit County that year was 66, lower than what it is now for African Americans in Summit County, which is following a national trend.

In July, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) put out a press release saying the national overdose death rates had increased 44% for Black people since 2019.

“The increase in overdose deaths and widening disparities are alarming,” said Dr. Debra Houry, CDC's acting principal deputy director.

The CDC pointed out the national crisis was unfolding against a backdrop of COVID-19 disruptions.

The videotaped police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis added to that stress, said Kemp Boyd, who serves as executive director of the Christian-based non-profit Love Akron, along with coaching the football team at Garfield high school.

“As Black males you’re looking at someone who looks like you being murdered by a police officer,” Boyd said.

Boyd didn’t mention it, but in Akron, the community last year also saw videotape of another Black man, Jayland Walker, shot and killed by police. That case remains under investigation by state officials, and the officers involved went back on administrative duty last year.

Boyd said he wonders how many overdoses may be intentional as Black people try to cope with stress.

“I just believe mental health is such a big issue that we have to normalize the conversation of mental health,” he said. “As people we're all struggling with trauma, and the Summit County ADM is helping to raise the awareness of the resources available for those in need.”

Summit County ADM board and its public health department are working with Kemp and others in the Black community to drive down rates of both suicide and overdoses, reaching out to Black residents through the faith community, barber shops and other neighborhood efforts.

What's being done in Summit County to combat the opioid crisis?

A lot has changed since the opioid crisis began in Summit County.

The waiting time for detox was about seven days in 2016. Now, it’s zero, said Dr. Doug Smith, chief clinical director of ADM.

“Anyone can be dropped off or walk in 24/7 to start on a path of care,” he said.

Beds have been added for those who need inpatient recovery at the Interval Brotherhood Home in Coventry Township, which was founded originally in 1970 to help those with alcoholism.

There also are more intensive outpatient options, including the nonprofit Urban Ounce of Prevention, which was founded in 1990 by Evaughn Cagle to serve Akron’s African American residents.

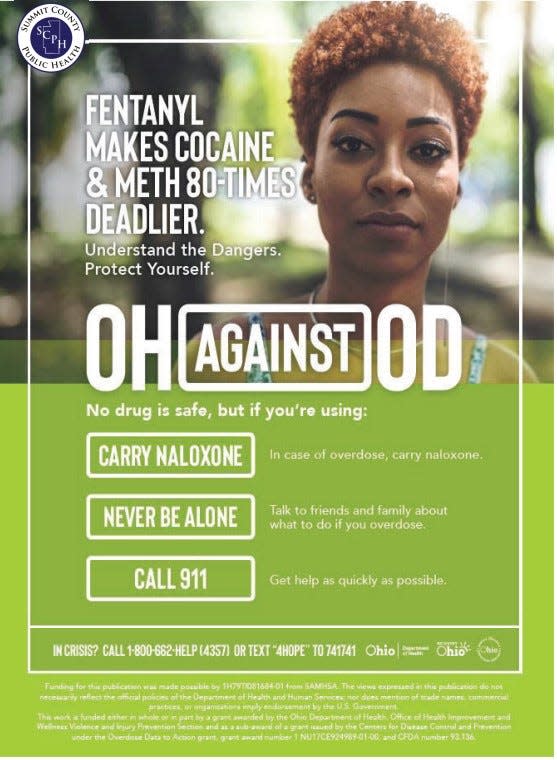

Naloxone, the nasal spray mist often known by the brand name Narcan that can reverse opioid overdoses, is now widely available at drugstores and for free at ADM.

The white community demanded those changes, and now the Black community can benefit from them if officials can reach them.

A community survey revealed one obstacle, an ADM official recently told Akron City Council: Black men in particular see drug addiction as a weakness rather than a disease.

To combat that myth and others, Summit County health officials last year began running ads before films at movie theaters with large Black audiences.

“True or false?” one ad asked. “Giving someone Narcan encourages or enables the opiate-user.”

The answer is false. “Giving someone Narcan gives the person suffering from an overdose the chance to seek treatment and more importantly, another chance at life,” the ad said.

Officials also sent postcards to people in Black neighborhoods telling residents how they could get free nasal spray kits of naloxone.

The response was overwhelming, with Narcan requests to ADM skyrocketing 700% over four months last summer.

“If I’m living in a neighborhood and I know people are dying, I may not want to go to the health department to get a kit, but if I can do it quietly, I will,” said Smith, the ADM clinical director.

ADM plans to do another postcard campaign this year.

“We’re trying to meet people where they are,” he said.

Arrington said help can’t come soon enough.

Health officials said fentanyl-related overdoses among men in Summit County tend to be among the middle-aged, with an average age of 47 or 48.

But Arrington said he started noticing an uptick in fentanyl use among the Akron AIDS Collaborative community, which is much younger, mostly ages 18-29.

“The gay community is smoking meth left and right, and it’s laced,” he said.

Arrington said he put in a request to health officials more than a month ago to keep a stockpile of naloxone at the Bayard Rustin LGBTQIA Resource Center in Akron’s West Hill neighborhood.

He also requested public health officials speak to his group’s weekly Wednesday dinner to explain how to use the life-saving nasal spray.

“But I’m still waiting … and people are out there buying Xanax and it’s really fentanyl, or Ecstasy, and it’s really fentanyl,” Arrington said. “Fentanyl is everywhere.”

How to get help

ADM can connect you to treatment options close to your home in Summit County. The Addiction Helpline is 330-940-1133. ADM also offers a mental health hotline: 330-434-9144.

To reach Urban Ounce of Prevention in Akron, call 330-867-5400.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Fentanyl devastating Akron's Black community during opioid crisis