Who is fentanyl hurting in Tri-Cities? The answer might surprise you. What can be done?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A nurse and a young man expecting his first child might not be who you imagine when trying to picture someone battling a fentanyl addiction.

But for those two Tri-Citians, that’s just one part of who they are.

Both have since found success in recovery and work toward helping others who are trying to start their own journey toward getting clean.

Benton Franklin Superior Court Judge Joseph Burrowes was almost like a proud parent watching Shaun Lettrick speak at a recent roundtable discussion on fentanyl hosted by Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-WA.

Lettrick had been asked to speak at the senator’s roundtable in the Tri-Cities, offering his perspective as someone who had lived through addiction and recovery.

Just a few years ago he was a defendant in Burrowes’ Adult Drug Court, after being arrested for stealing to support his addiction.

Instead of being sentenced to jail, Burrowes gave Lettrick the opportunity to get clean and be there for the baby he had on the way, while being accountable for his actions.

On the other side of the room, Melissa Cross got the opportunity to talk about her own journey and advocate for her patients. From addiction to a felony charge, and having to give up her nursing license for a time, Cross knows what they’re going through because she has been there herself.

Today she works directly with people in recovery, helping them find their own way forward.

Road to recovery

It’s possible that neither of them would have been in the room to offer their insight had they not been given a chance, and the resources, to choose recovery.

Lettrick told the Herald his addiction started when he began taking pain medication to deal with the aches that came from long days at his restaurant job.

“I was working at a restaurant and I was standing all day and my body was hurting,” he said. “A friend said, ‘Hey I’ve got a prescription for (Oxycontin), why don’t you try ‘em?’ So I took a couple and started to notice I could work a lot longer. I felt more loose. I felt more comfortable.”

Lettrick said it wasn’t long before he started taking something stronger, and his life fell apart.

“After doing that for about a year I got introduced to fentanyl, and once I got on the fentanyl that completely changed everything,” he said. “I started stealing, robbing people. I lost my job, I would spend all my money on it. I did that for many, many years.”

After awhile, Lettrick was stealing to support his addiction as his motivation turned from getting high to just trying to stave off withdrawals.

“The withdrawals, that was the biggest thing for me, people don’t realize that when you’re taking fentanyl, it gets you high but after a certain point of doing it, it doesn’t get you high anymore. You’re doing it just so you don’t get withdrawals,” he said.

“The withdrawals are horrible. You’re throwing up. You’ve got restless leg syndrome. You’re hot and cold. You feel like you’re dying inside. You’ll do anything to not feel like that.”

He managed to get into treatment, and it stuck for about four months, but then he said he fell back in with friends he shouldn’t have been hanging out with and started using again.

Then he got arrested again, and this time Lettrick was looking at years in prison.

Cross said her addiction began about a decade ago when she was working as a nurse at a local hospital. She began using and then got caught stealing fentanyl.

She said her addiction led her to going against all of her own values and ethics. Today she’s grateful that the strict controls at the hospital led to her getting caught quickly, and kept her from taking medications directly from patients.

She was charged with a felony and had to give up her nursing license for a period of time. While she was working her way through treatment and court, she decided instead of picking up trash for community service, she would reach out to a local recovery organization to ask if her training and experience could help them.

That’s how she began working with Blue Mountain Heart to Heart, a community health and recovery organization that started in Walla Walla almost 40 years ago. At first the organization focused on advocacy for HIV patients, but eventually incorporated other public health initiatives.

As part of the plan to get her nursing license back, Cross said she had to go through a program that requires longer than the typical 28-day, in-patient stay.

“The thing is that when you’re a professional and you want to keep your license, you have to go to treatment for longer,” Cross said.

She said that studies have shown that the longer someone is in in-patient treatment, the more likely they are to have long-term success. Typically that’s 60 to 70 days, but she said the doctors in her program were required to be there for three months.

“That’s something I find frustrating with my own patients to this day, that they’re moved out before there is any kind of assessment whether they’re ready,” Cross said.

After completing her community service, she began working full-time with Blue Mountain, even helping open their Tri-Cities clinic.

Seeing the person

Although their stories started differently, Cross and Lettrick have one key factor in common — someone saw their potential and treated them not like just an addict, but a whole person.

It’s something that Cross carries with her every day in her own work.

“I think that’s where our case management services and how we come to care for our patients … is really helpful. Our motto is meet people where they’re at,” she said.

“We want to wrap our arms around them and say, ‘What do you need?’ Identifying not what I think is their biggest need, but what do they see as most important? What’s going to give them purpose? What’s going to give them joy? Because that’s what’s going to sustain their recovery.”

For Lettrick, it was his family.

He got clean just in time to be there for his daughter’s birth, and he’s committed to doing everything he can to keep being the father she needs.

He said if it wasn’t for the support and encouragement from Judge Burrowes, he’s not sure he would have made it.

“He’s watched me go through the whole program, from going in looking like crap to struggling to try and work the program to actually working the program,” he said.

“He’s a great judge, he’s phenomenal,” Lettrick said. “He made me feel like an actual person for the first time. When you’re stealing and, not necessarily living on the streets, but using, people just look at you different.”

While there were plenty of tangible needs and programs discussed at Sen. Cantwell’s roundtable, one thing that kept coming up was the idea that hope and compassion are needed to help someone recover.

“A lot of people in recovery have tried treatment multiple times, and that’s okay,” Cross told Cantwell. “When we look at recovery and treatment, there are so many different paths and traditionally we have said, ‘This is the only way’ when really, everyone needs to decide what it’s going to look like for them ...”

Cross said she works hard to keep spirits up for law enforcement, medical personnel and jail workers who might be struggling with seeing the same people keep coming back. She said it’s important that they all see people struggling with addiction as someone who can get better.

Cross said that in her interactions with front-line workers, if they feel like they are losing hope for the patient, they can “borrow hers for a minute.”

Recognizing the disease

“Addiction is a disease” is a phrase most people have heard.

It’s often used to combat misconceptions that people struggling simply choose to get keep abusing drugs or alcohol rather than function in society.

In recent years Substance Use Disorder has been recognized as a medical condition and has gained greater cultural clarity, but the current definition has only been around for about 10 years.

Like many mental health and medical conditions, definitions and symptoms have evolved over the years as understanding of the condition has improved.

The DSM-5, which is used by mental health professionals to help diagnose conditions, merged substance abuse and substance dependence to create the broader term in 2014. This newer classification puts greater emphasis on the underlying medical reasons for addiction.

But the stigma around the substance use and addiction still plays a major part in public perception.

It is an issue that you cannot simply educate your way out of, or solve with programs like D.A.R.E., BFHD’s Senior Management of Healthy Living, Carla Prock told Cantwell.

While education helps build awareness, the emphasis on “saying no” or programs that just discourage drug use won’t address the legitimate medical concerns that cause addiction and lead people to fentanyl use.

These programs aren’t effective uses of political funds or capital, roundtable participants said.

“This is a medical diagnosis, it isn’t a moral failing, though there is some evidence of generational and systemic causes ... “ Cross told the Herald. “We really need to move away from looking at this as if it’s a behavioral choice and more into the idea that this is a medical diagnosis with a biophysical reason, which means you can’t educate out of it.”

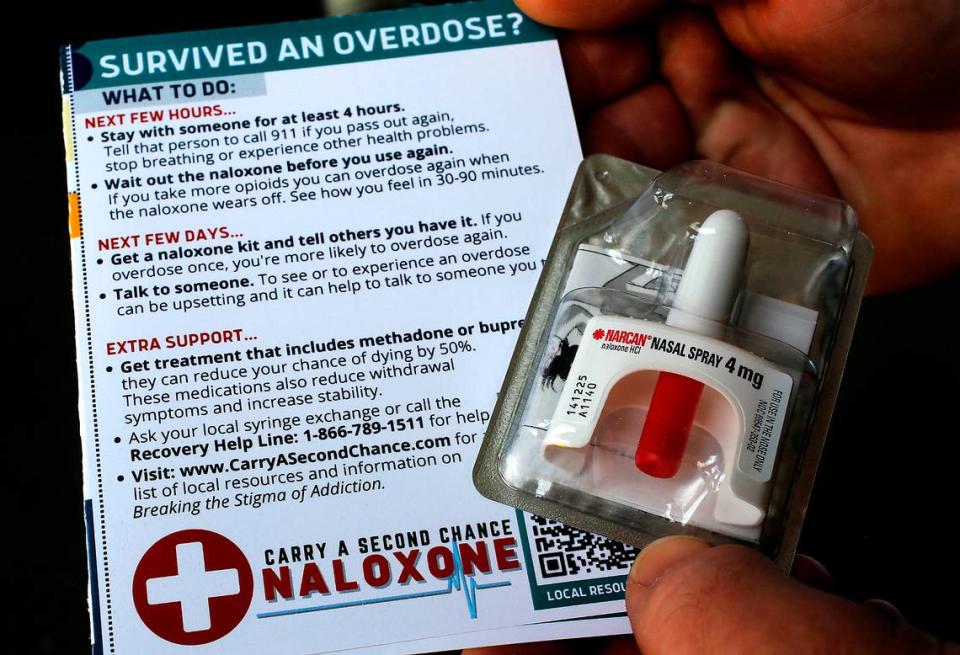

What is needed most is ready access to life-saving Narcan, also known as Naloxone, Kadlec Emergency Medicine Director John Matheson said. He pointed to initiatives in other cities to begin putting out Narcan boxes around the community, like AEDs and fire extinguishers.

Blue Mountain is one of the places that drug users can go to get clean needles, medication to help with addiction and free access to Narcan. Cross said that since helping open Blue Mountain’s Tri-Cities location in Pasco in 2019, they’ve had to move three times due to push back from people who didn’t want the needle exchange nearby.

Blue Mountain’s Kennewick office is more than just a needle exchange. They have providers on-staff who provide medication for opiate use disorder, which includes Suboxone and Sublocade.

Cross said that this medication based intervention can be especially important because medications such as Suboxone have the highest efficacy rates for long-term recovery when someone does not have access to multiple forms of support of treatment.

“It’s actually damaging to people both in recovery and people who may still be using drugs,” Cross said. “Access to services is always difficult and the population we serve tend to have difficulty with transportation and access to simple things in daily life that we’re used to, like Google Maps.”

Cross said that today experts recognize that medication is not just a supplement to recovery, but often the primary foundation.

The push back Blue Mountain has been met with could now also be limiting access to Narcan for people who cannot get to the new facility in Kennewick at 911 S. Auburn St.

That means people staying in the Tri-Cities’ only shelters, or near them to access services they offer to people experiencing homelessness, are now across the river from treatment services offered by Blue Mountain.

For those concerned that more access to Narcan will lead to fentanyl use in their neighborhoods, it’s important to recognize just how widespread the problem has become.

An analysis from the Congressional Budget Office has said that as access to prescription opioids became more restricted in the last decade, it led to a rise in use of illicit fentanyl, meaning many people who were on addictive prescription pain medication lost access to it and turned to the drug.

Who is dying in Tri-Cities?

The Benton Franklin Health District has stressed that anyone can be impacted by fentanyl.

The vast majority of people who have died from overdoses in the Tri-Cities have not been homeless or unemployed. One of the largest risk factors for death with fentanyl use is with people using alone at home.

The health district’s most recent data shows that men ages 45 to 54 are the most likely to die of an overdose, and those working in construction, hospitality and agriculture are among the highest risk groups.

Of the more than 330 people who died from overdoses in the Tri-Cities between 2016 and 2022, only 18 people were listed as unemployed and another 10 were considered unemployed due to disability.

About one-third had some college credits or a degree. Only 79 did not have a GED or high school diploma.

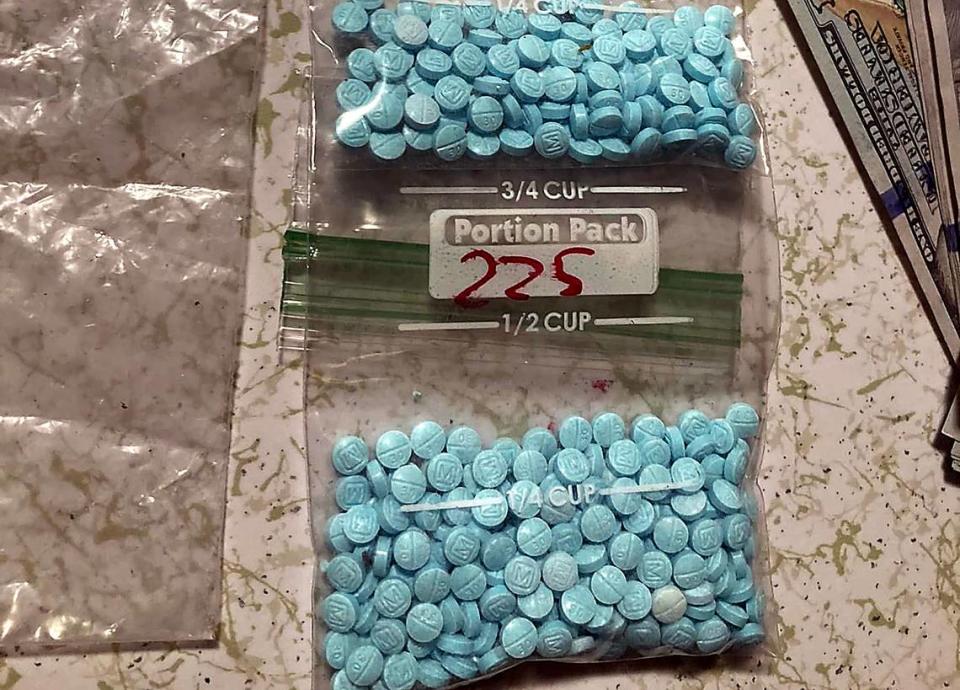

With fentanyl down to just $3 per pill in the Tri-Cities area, and more than 200,000 doses seized by the Metro Drug Task Force already this year, Kennewick Police Commander Aaron Clem told the roundtable it’s easier than ever to get.

Cross said that despite her education, stable upbringing, resources and family support, she still fell into addiction.

She said she recognizes how much privilege she had, and credits part of her success in overcoming her addiction to being able to more readily access resources and go to rehab for longer.

She wants everyone to have that same access to help and support.

Lettrick hopes that others who have been in their shoes will reach out for help before it’s too late.

“They can do it. You’ve got to sort of look at the bigger picture and say that you’re worth it, you can get through it. There are people out there that care for you,” he said.

“Go to a meeting, there’s tons of resources. If you apply yourself to it, you can come out on the other side.”

Tri-Cities treatment resources

Benton Franklin Health District maintains a list of treatment options and support in the Tri-Cities area. Those resources include:

Medication for Opiate Use Disorder

Ideal Options: Kennewick 877-522-1275

Lynx Healthcare: Kennewick 509-591-0070

Support services

WA State Community Resources: Dial 2-1-1 (healthcare, mental health, housing, food, legal aid, domestic violence, etc.)

Narcotics Anonymous Tri-Cities: 833-437-3480

Blue Mountain Heart to Heart: Kennewick 509-905-2053

Merit Resource Services: Kennewick 509-579-0738

First Step Community Counseling Services: Kennewick 509-735-6900

Somerset Counseling Center: Richland 509-942-1624

Lourdes Pasco: 509-547-9000

Hotlines

Washington Recovery Hotline: 866-789-1511

Alcohol Drug Helpline: WA - 206-725-9696 or National - 1-800-662-4357

24-Hour Crisis Line: 866-4-CRISIS (866-427-4747)

988 Lifeline: Just dial 988