How the Ferrari 250 GTO Became a $70 Million Car

When it first appeared, the car had no name. But Ferrari staffers had taken to calling it “Il Mostro”—the monster—because of its strange looks. The date: August 11, 1961. The place: Monza. The racetrack’s sprawling grandstands were empty as technicians rolled this new Ferrari prototype into the pits under the watchful gaze of Giotto Bizzarrini, the genius designer and engineer who could take more credit than anyone else for getting the car this far. The vehicle had no paint, its tarnished aluminum body the color of an angry sky. Its front end looked particularly awkward, with intakes that made it look like it was gasping for air through a taught mouth and a trio of nostrils. A Belgian Ferrari team driver named Willy Mairesse hammered the engine and pulled the car out onto the track for its debut shakedown.

Bizzarrini was all nerves. The imperious boss Enzo Ferrari was expecting the new racing car to be a world-beater. Meanwhile, the driver Mairesse always put people on edge. Enzo’s deputy Franco Gozzi remembered: “Willy Mairesse had been involved in many shunts and became known as a car crasher.”

Remarkably, the vehicle was not a white-sheet design. Instead, it had been developed mostly from existing components. The chassis came directly from the 250 GT SWB, but the front-mounted engine had been moved lower and more midship, closer to the cockpit. The motor was the proven 3.0-liter V-12 from the Le Mans-winning Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa, the engine that more than any other had earned Ferrari a reputation for sophistication and victory. Enzo once said of this powerplant, “All we wanted to do was to build a conventional engine. Only one that would be outstanding.” Its 12 cylinders were the diameter of silver dollars and revved at such high rpm that the motor had become known—more than any other that had ever been built—for its song as well as its performance.

When members of the racing press got their first look at the new Ferrari, the reaction was unfavorable. One reporter called it “the anteater” because of its weird nose. The prototype might have looked ungainly, but one thing was clear: it was quick. Powerful, easy to drive, and loud as all hell.

Ferrari had never produced a car that, in its own way, was not outstanding, and there was no reason to believe this new vehicle would stand out more than its predecessors. No one could know at the time what we now know about this prototype. When fully developed, it would come to be called the Ferrari 250 GTO—250 for the cubic-centimeter displacement in each of the 12 cylinders, GT for gran turismo, and O for omolagato, the Italian word for homologation. Six Weber carburetors, roughly 300 hp, a new five-speed transmission to replace the four that Ferrari had been using for years, top speed of roughly 175 mph. Nearly 60 years after the debut shakedown at Monza, the GTO has become today the single most coveted automobile ever built, since Karl Benz made the first one in 1896. It was the last of the line of front-engine Ferrari racing cars, and the last Ferrari ever made that was not only a winner on the track, but also an easy-to-handle road car. Today, despite the tepid reaction of the press in the summer of ’61, the GTO consistently tops lists of hottest cars and greatest Ferraris of all time.

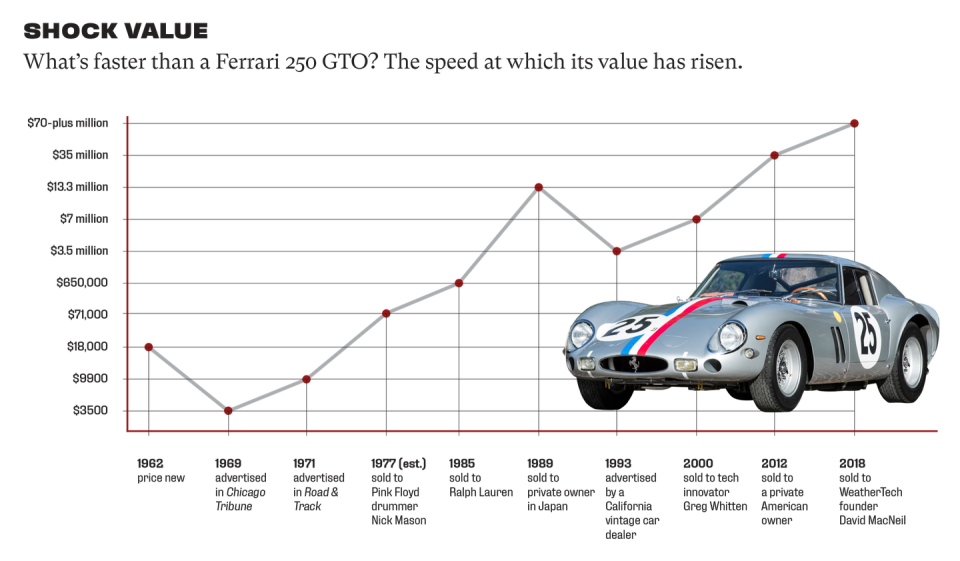

The most money ever paid for any car was more than $70 million, in 2018. It was a 1963 Ferrari 250 GTO. The most money ever paid for a car at auction was $48.4 million, that same year. It was a 1962 Ferrari GTO. Not every music fan can agree that “Stairway to Heaven” is history’s greatest rock song, nor will all sports fans agree that Muhammad Ali is history’s greatest athlete. But in the car world, the GTO has become the Greatest of All Time. The GOAT. And this fact is quantifiable, far and away, in dollars and cents.

What is often lost on the world today is the extraordinary story of how this car came into being, and the equally astounding story of how in recent years it has become an automobile worth more than mansions sitting on their own private islands.

At the time of the GTO’s first laps at Monza, Ferrari’s company was just over a dozen years old, founded in a bombed-out World War II factory in the village of Maranello, outside of Enzo’s hometown of Modena. During the 1950s, his race teams—both sports cars and Formula 1—had become preeminent, and he himself had become an enigma—elusive, eccentric, and feared. He was known as “the Magician of Maranello.” Though he was neither an engineer nor a designer (by his own assessment, he was an “agitator of men”), his racing and road cars had come to be the most exotic in existence, and they were embodiments of his particular genius. However, competition from the Brits—notably Aston Martin and Jaguar—was gaining, on the track and in desirability among rich clientele.

In 1961, as the GTO was being developed, the Ferrari racing team conquered Europe’s racetracks completely. Ferrari won Le Mans in June for the second year in a row, and by September two Ferrari drivers were gunning for the F1 world championship—the American Phil Hill and the West German libertine Count Wolfgang Von Trips, whose nickname was Count Von Crash. On September 10, 1961—one month after the GTO prototype’s first shakedown run—Phil Hill became the first and, to this day, only American-born F1 world champion. But on that same day, his teammate and rival Count Von Trips lost control of his car. The Ferrari scythed through a crowd of spectators. Von Trips was killed, along with 14 spectators.

Ferrari drivers had died in competition before. But unlike those accidents, Von Trips’ crash had been captured by a television camera. The footage shocked the world (and continues to: it has hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube). The next day’s front page of Italy’s biggest newspaper, the Corriere della Sera: “Fifteen Dead from the Tragedy at Monza. The Investigation Has Begun at the Autodrome.” Reporters were all but pounding on Enzo Ferrari’s office door. “You can’t imagine what it was like,” the late Phil Hill later recalled. “It seemed like everybody in the damn country was milling around Maranello, and there’s Enzo Ferrari, with three days’ beard growth, and wearing bathrobes all day.”

Over the next couple months, the stress of the bloodbath at Monza built, and in November it boiled over. Eight key men walked off the job in what is now known as the “Palace Revolt.” Among the departed was Giotto Bizzarrini, the lead engineer on the GTO (shortly after, Bizzarrini was hired by a tractor maker in nearby Bologna named Ferruccio Lamborghini to build a V-12 for his first car).

So during the final critical months of the GTO’s development, the Ferrari empire was collapsing; it was the most troubled time in the company’s short history. Ferrari had to move on with inexperienced talent. “We got rid of the generals,” he told these men. “Now you corporals must take charge.”

By the time the Ferrari 250 GTO debuted at its first official press conference—at the factory on February 24, 1962—a new chief engineer had taken over, Mauro Forghieri, just 26 years old. Il Monstro’s shape had been refined, and its aerodynamic Scaglietti-built body had become a thing of distinct beauty. Stirling Moss, arguably the greatest racing driver alive at the time, had helped with on-track development of the prototype. The price tag for the production car was $18,000 (about $153,000 in today’s dollars), and only buyers personally approved by Enzo would be allowed to pay for one. As it would turn out, only 39 would ever be built. (While this number is often disputed, the Ferrari factory today confirms it.)

On March 24, 1962, the GTO made its racing debut at the 12 Hours of Sebring, and today it’s easy to imagine this feast of sound and speed to be the dawning moment of the Golden Age of sports-car racing in America. The competition featured first-generation Corvettes, a Jaguar E-Type, various Porsches, MGs, Maseratis, one Ford Falcon, and a dozen Ferraris. The GTO won its class and placed second overall behind a Ferrari Testa Rossa, and from there on the new Ferrari began to steamroll the competition.

“I raced a lot with the GTO,” remembers Jean Guichet, now 92. “First as ‘private driver’ in 1962 and 1963, and then as an official driver for the Scuderia Ferrari in 1963 and 1964.” Guichet won Le Mans in the GT class (second overall) in the car’s debut at the Circuit de la Sarthe, and the following year he won the Tour de France and the Six Hours of Dakar in the GTO. “The GTO is one of the most beautiful racing cars ever made,” he recalls. “Fast and one of the only multi-purpose racing cars. The GTO was perfect whatever the conditions and the type of race.”

A few GTOs made it to America in 1962, through Ferrari’s U.S.-based distributor, the famous Luigi Chinetti, who sold them to fabulously rich, hand-picked Americans, per the Ferrari business model. “I drove the Ferrari GTO in four races in the early 1960s,” remembers Roger Penske, “racing for John Mecom, and we finished first overall or first in class in three of those races, so I certainly have great memories of that car. I remember it was a very powerful car, and it was a lot of fun to drive.”

When Carrol Shelby’s Cobras first arrived on the scene to take on the GTOs in 1963, the excitement captured the imagination of a new generation of race fans. One Shelby driver, Allen Grant, raced in both the Cobra and the GTO and is today uniquely qualified to compare the two.

“The Ferrari GTO was a very sophisticated, refined car, as opposed to the Cobra,” says Grant. “As we all know, the Cobra was a more simple car. It was a hot rod. The engine was extremely explosive. When you stepped on the gas, man, you better be ready as your back end would go flying. Whereas the Ferrari V-12, you stepped on the gas and it would go two-thousand, three-thousand, and at about 4000 rpm, all the sudden, it would accelerate faster. It came on smoothly and gradually. In corners, you would dirt track the Cobra. You came in hot, hit the apex and drifted all the way through. Whereas the Ferrari you drove conventionally. The Cobra had a production four-speed Borg Warner transmission. The Ferrari transmission was more precise. It was a gated five-speed. Click, click, click. Very refined.”

The GTO went on to win the GT world championship in each of its first three years, until it was beaten by Shelby’s Cobras in 1965. At which point, it became obsolete and entered into the next phase of its legacy. It never won Le Mans outright, only the GT class. The FIA rules dictated that a manufacturer had to build 100 examples of a car to homologate it for GT racing; Ferrari had only built 39 GTOs, but so powerful was Enzo Ferrari, the team got away with it. (He wasn’t the only one bending the rules.)

In 1963, Ferrari debuted its first 12-cylinder mid-rear-engine sports racing car at Le Mans, the 250 P (for prototype, as opposed to GT-class racing cars). It won Le Mans outright in its debut, and soon the GTO was pushed aside. As Guichet explains: “The development of Ferrari racing cars was rapid; every year the cars were extensively modernized. In order for me to win I had to race with the latest version, and precisely that’s what happened. Every time a new generation came out, the previous one became obsolete and worth nothing. And it was the same for the 250 GTO when the rear-engine Ferraris arrived.”

In the mid-1960s, the racing world moved on. The Ford GT40s arrived at Le Mans, and for the first time, huge audiences in America could watch the race live on ABC's Wide World of Sports. Competition is the impetus for innovation. During the GTO’s reign in the early 1960s, top speeds on the Mulsanne Straight at Le Mans were in the realm of 175 mph. By 1967, the Ford Mk IV was exceeding 210 mph. Then came Porsche’s 917. Can-Am took North America by storm. A.J. Foyt and Mario Andretti drew unprecedented audiences to the Indy 500, while Formula 1 was growing more technical, rich, and global. Television, advertising, tire wars, the transcending fame of athletes—all of it pushed racing into the first era of big-time international sports.

And what of the GTO? The vintage racing world and the car-collecting world we know today did not yet exist. An analysis of newspaper classified ads tells the story. On April 13, 1969, the New York Times ran a classified ad for a “streetable” 1962 GTO for $9450. A week later, the Chicago Tribune ran a classified for a “95 percent mint cond.” GTO for $3500.

“I remember not that long ago relatively speaking, I want to say in the early 1970s, when the late Kirk F. White started his auctions, they had a GTO for $7500,” remembers Ken Gross, the auto historian, museum curator, and longtime Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance judge. (White is known as the founder of the vintage car auction industry.) “People thought, well that’s nice, but it’s an old race car. It’s not something you could compete with, so why would you want it?”

The surge in value began not with the car but the car scene. The generation of young race fans who grew up entranced by Ferraris and Cobras in the 1960s got older and more moneyed. Vintage auctions started to become a phenomenon. The Monterey Historics and the Pebble Beach Concours started to draw big crowds and traffic jams. Vintage racing went from a hobby to something so much more. Meanwhile (and sorry to offend some readers), cars lost their artistic beauty to some degree. The vehicles of the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s could never match the hand-built artisanship of the vintage classics.

Suddenly, old cars were going for a lot of money—Jaguar E-Types, Mercedes Gullwings, prewar cars, and all manner of Ferraris. When Enzo Ferrari died in 1988, the values of classic Ferraris were already soaring, but with Enzo gone, never again would a Ferrari roll out of the factory under his gaze. There was now a finite number of so-called “Enzo era” cars. A month after Ferrari’s death, the Minneapolis Star Tribune ran an article with the headline, “Value of Classic Ferraris Soaring to Major Nest-Egg Proportions.”

Meanwhile, with the economy booming in the 1980s, the GTO surged to the forefront, once again leading the pack. Ralph Lauren bought chassis #3987 in 1985 for $650,000. A year later, the collector Frank Gallogly bought a GTO for a million. Values crashed during the mid-1990s recession but quickly surged again with eyebrow-raising speed. In May 2012, a GTO reportedly went for $35 million. Last summer, the Italian courts ruled that the Ferrari 250 GTO was in fact a piece of art, and thus it is now illegal to replicate or reproduce it.

It all begs the question: Why the GTO—a vehicle that never won Le Mans outright—above all other Ferraris? Above all other cars, period, when it comes to value? Owners of 250 GTOs today can single out some reasons.

“If you had to choose one car that was emblematic of an era, that just ticks every box, it really is the GTO,” says William “Chip” Connor, the Hong Kong- and U.S.-based businessman and longtime vintage racer who bought chassis #4293 around the year 2000. “They only made 36, just 33 of the series 1 type. So you have rarity and you have spectacular history. It won the world championship of makes for three successive years. The car was not revolutionary or groundbreaking. It was evolutionary. It really was the coming together of everything that Ferrari was doing in the way of charismatic front-engined GT cars. It came almost to perfection with the GTO. It evolved as being that incrementally more special thing to own.”

Another part of the car’s aura comes from the tiny community of lucky owners themselves—men like Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason, Ralph Lauren, and former Microsoft president Jon Shirley. “About 30 years ago they started having these rallies every five years and the owners started getting together and they developed an affinity for one another,” says Connor. “They unified around the cars. You have this car that is rare, that is appreciated by people who really know what they're doing. There’s a disproportionate number of owners who race these cars, which is something you don’t find with many collectibles. And so you put all that together and it explains why there’s such demand for them.”

Tom Price is another owner (chassis #4757). He built an auto dealership empire on the West Coast and bought his GTO in the early Eighties. He has raced it more than 200 times, in the U.S., Europe, even Australia. To answer the question of why the GTO has become the GOAT, he says, “It is a combination of things. It is of that era when Ferrari really established its reputation. It’s an absolutely gorgeous car. And it’s a phenomenal car which you can drive on the street to the track and then race, which I’ve done numerous times. There is just something about it—the sound, the feel, the handling. It’s something that is unique.”

All of which begs the question: If the 250 GTO can be called the GOAT, is there a GOAT of the GOATs? Is there one specimen that can be singled out as the finest? Well, there’s chassis #4153, which was purchased by the founder and CEO of WeatherTech, David MacNeil, in 2018 in a private sale for upwards of $70 million. The story begins somewhere around 2016, when MacNeil let some powerful auctioneers know that he was in the market for a “spectacular GTO.”

“I didn’t want to get one that had been crashed, I didn’t want to get one that had been rolled over,” he says. “I wanted one that was of the highest caliber from an international racing standpoint, the highest caliber from a condition, provenance, and history standpoint." MacNeil subscribes to the "only cry once" philosophy. Meaning, if you save a few bucks and don't buy the car you really desire, you'll cry every time you see it, but if you pay top dollar for the perfect specimen, the only time you cry is when you write the check. "But every time you see that car, you’re going to go, Hell yeah! I’m going to drive that thing so hard!”

MacNeil’s GTO placed fourth overall at Le Mans in 1963, and won the Tour de France that year. A car with that kind of competition history—that has never been crashed—does indeed make it unique. When news of MacNeil’s purchase spread, the New York Post ran the headline: "'Holy Grail' of Ferraris Sells for Record $70 Million" (it was actually more). Does he contend that his car is the finest GTO of them all?

“That might be a bit arrogant,” he says. “I have been told by experts that it’s one of the top three. So you can argue that it’s the best one or one of the best three but it’s right there at the top.” And how does the man who owns the most highly valued singular car on earth define its greatness? “There are a lot of vehicles that are good at one thing and not others. But the GTO is good at everything. And the shape is just spectacular. From outer space, from the Hubble Telescope, you can look down on earth and recognize it. The aesthetics, the dimensions, the proportions, everything about it says speed and beauty. The pure joy of shifting it hard, driving it aggressively.... How it performs, how it feels, and importantly, how it makes you feel as a driver. This is the GTO.”

MacNeil likes to share the car with his kids, because sharing the car with the next generation is key, he says. Will these GTOs hold their values in the future, for the Uber generation? MacNeil believes the values will only go up, and experts agree.

“Can the price go up?” asks Gross. “I think it can and I’ll tell you why. I believe many fine automobiles can be considered rolling sculptures. They are 20th-century industrial art. If you think of the extraordinary price of some paintings and then you look at the GTO, it may be that these cars are undervalued in terms of where the future will go. If you look down the road 10 years, 20 years, you’re going to have more and more electronics controlling cars. When internal-combustion cars are no longer made, their ancestors will only be considered more rare and special.”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos