With few beds, fewer psychologists, Georgia inmates wait months for mental health evaluations

The waitlist for competency evaluations by the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health (DBHDD) continues to grow as does the one for beds at state mental health hospitals. As a result, inmates at Georgia jails, including those at the Chatham County Detention Center (CCDC), are incarcerated for pending charges without sufficient treatment.

Statewide, Georgia has experienced a 40% increase in court orders for pretrial evaluations since 2006, yet the state has 35% fewer forensic psychologists to determine defendants’ competency, said DBHDD Commissioner Kevin Tanner at an October budget proposal meeting.

Tanner said that, as of Sept. 1, more than 1,200 defendants statewide were awaiting a pre-trial evaluation, a number that has exploded in recent years.

There is also a waitlist for defendants found incompetent to stand trial and referred for treatment at a state hospital. At the end of September, 523 people around the state were waiting for a bed in one of the state's five in-patient mental health facilities, including Georgia Regional Hospital on Eisenhower Drive. The current wait time in Georgia is 275 days, much higher than most states, where wait times typically average 30 days (although three states have reported wait times ranging from six months to a year, according to academic research).

In Chatham County, the issue is as acute. According to court records, as of Oct. 17, 26 people were awaiting a pre-trial evaluation and 15 people were awaiting bed space at a DBHDD facility.

Chatham County Courts in 2015 implemented the competency docket, modeled after the Northeastern Judicial Courts. Back then, Chatham County Superior Court Judge Penny Freesemann said the court would receive an initial opinion on competency from DBHDD within 30 days.

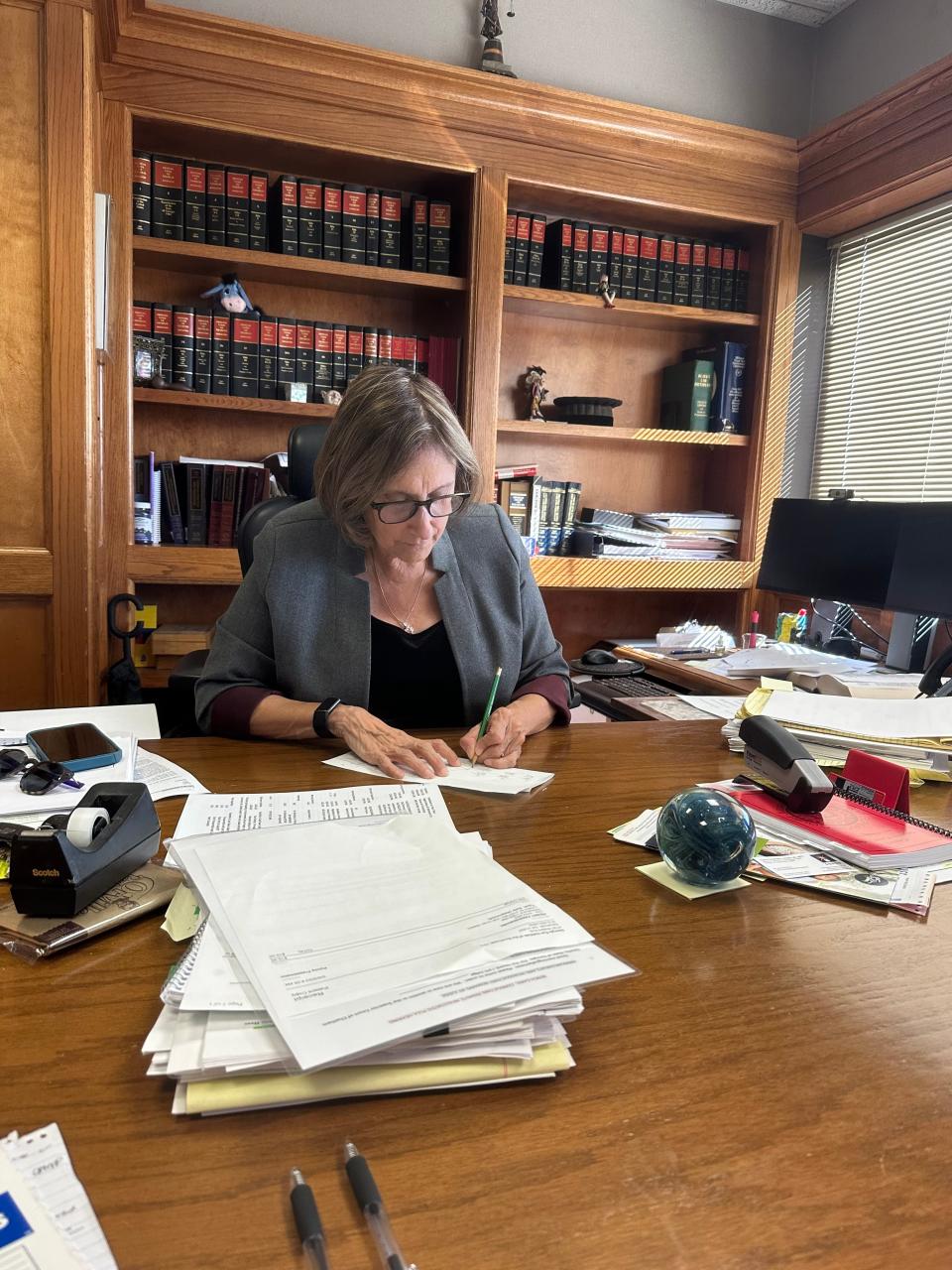

Freesemann, who presides over the mental health court and competency docket, said in late October that the wait is now at least six months. “I know that when I get on a docket when someone's talking about,’ I'm going to need an evaluation,’ I cringe a little bit and there’s probably a year away and that person is just sitting in the jail.”

AP Report: Attorneys for family of absolved Black man killed by deputy seeking $16M from Georgia sheriff

New Development: Chatham County District Attorney appeals federal judge's sanctions in discrimination case

Bottlenecks in evaluation and treatment process one cause of backlogs

The competency docket occurs monthly and is divided into two sections: the competency pending docket and the competency review docket, all of which are live streamed to the public.

There are two points in the competency process, Freesemann explained, where the backlog visibly increases.

Further Reading: What is the process for determining competency?

The first occurs in getting the initial forensic evaluation. "[It] can take months, and months and months,” said Freesemann.

Most defendants remain in jail as they await the initial evaluation. And even after the lengthy process to determine competency and treatment options, Freesemann estimated that lawyers agree on the defendant’s competence 80% of the time.

Freesemann said the bar to stand trial is pretty low. "In theory, you could be hearing voices, but as long as you could set them aside and as long as they aren't interrupting me from having a conversation with you and following what's going on.”

If Freesemann rules a defendant competent to stand trial, the regular trial schedule resumes. If Freesemann finds them “probably restorable,” the defendant is placed on a restoration list, which is where the second bottleneck occurs.

With approximately 500 individuals waiting on the statewide list for restoration, the wait for a bed in a Georgia Regional facility is a year long, said Freesemann. "Georgia Regional definitely does not have 500 beds to treat people, and the entire DBHDD system statewide does not have 500 beds," Freesemann wrote in an email. "The lack of beds is one of the contributing factors to [the] statewide backlog."

She added, “And that doesn’t matter what they’re charged with. It could be something like shoplifting. [The backlog] will stop a shoplifting case, and certainly will stop a murder case.

“I hope the frustration doesn’t show on my face,” said Freesemann.

Still Missing: Despite search efforts, man who jumped from Talmadge Bridge on Sunday still missing

Chatham County lost its only forensic psychologist

Freesemann attributed the long wait for the initial evaluation to the lack of forensic psychologists in the county. For an initial evaluation to take place, a forensic psychologist must evaluate the defendant.

A forensic psychologist used to be assigned solely to conduct evaluations at the Chatham County jail, but in June 2023, she moved to another state for another job. After that, three to four doctors used to come in on a contract-basis.

For now, DBHDD is using forensic psychologists from other jurisdictions via TeleHealth, but that hasn’t fixed the issue, said Freesemann. “As of today, the legal side is moving as fast as it can go. But the medical side isn't. Three years from now, it could be the exact opposite. But right now, that's where the problem is.”

Chatham County Public Defender Fraser Klein agreed with Freesemann, also attributing the backlog to a lack of forensic psychologists.

In late November, the county hired a part-time forensic psychologist, but Klein believes the county needs two to three full-time forensic psychologists employed by DBHDD. “I mean, we had a backlog before that just because we only had one doctor doing all of that, and we have a lot. There essentially should have been two of her.”

Chatham County jail has become holding place for people with mental health needs

CCDC shoulders much of the county’s mental health issues. As of Oct. 13, 349 out of the 1,186 inmates in Chatham County Detention Center were being prescribed psychotropic drugs, according to CCDC records.

Within the first 10 minutes of an inmate coming into the detention center, a mental health professional screens the inmate. Within four hours of the inmate’s arrival, a registered nurse asks the inmate a list of questions to determine whether the inmate needs urgent or routine care. Still, according to CCDC records, eight of the 17 inmates who have died at the jail since 2016 committed suicide.

CCDC personnel insist they are doing what they can to address the issue. In 2017, CCDC implemented 20 suicide cells, including 12 padded cells. As of Oct. 13, nine inmates are on suicide watch.

“We've had people commit suicide in here because they're mental health people,” Chatham County Sheriff John Wilcher said in an interview in his office in February 2023.

“Everybody don't need to come to jail. People really need help out there. Somebody commits a horrendous crime and they need psychological help, we're going to provide it, but we can't do it so much here ‘til we get it to somebody that really knows what [they're] doing.”

Most often the jail is the holding pattern until a bed becomes available at Georgia Regional. “If they've committed a bad crime,” said Wilcher, “you don't want to send them out to the place [Gateway Behavioral Health] on Skidaway and DeRenne because that is not really a hold-'em facility like Georgia Regional is.

“Like I said when I came and took office,” added Wilcher, “I'm not a mental health hospital and I'm not a damn homeless shelter. And that's what they were doing, they were just piling them in here."

With new funding and programs, DBHDD envisions Chatham County as model for state

During an early November interview, DBHDD Commissioner Tanner called the backlog a “national problem.”

He described the perfect storm of the COVID-19 pandemic shutting down courts, the loss of more than 1,200 employees at Georgia hospitals, of which only 40% have been replenished. Then, once the courts reopened, American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds led to hiring more court personnel.

“We've seen a tremendous increase in the number of orders we're receiving because of that,” said Tanner. “So, shortage of workforce plus increase in orders, has resulted in a backlog. And again, that's something that we're seeing all across the country.”

A 2007 U.S. Department of Justice (USDOJ) investigation found that at the state’s then-seven psychiatric hospitals, there were patient safety concerns, patient-on-patient aggression and environmental problems, which led to the closing of two of Georgia’s facilities — Central State Hospital in Milledgeville and Northwest Regional Hospital in Rome.

“The Department of Justice wants these individuals served in the community, not in an inpatient setting, unless it's just absolutely necessary, so we're building up a very robust community-based system that is able to handle most individuals in the community,” said Tanner.

To that end, DBHDD contracted with two state-funded consultants to conduct a capacity study for a simple reason: “We wanted a non-political view of how many forensic beds are we short right now?”

In September, the consultants concluded that, by 2025, Georgia must build five more behavioral health crisis centers and create 120 additional beds in the state hospital network just for people in the criminal justice system.

A budget proposal by Tanner, which the DBHDD board unanimously approved in August, is meant to address the workforce and forensic backlogs.

According to a Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB) report, the proposal includes $15 million in one-time funding for crisis center staff wages, $10 million to boost the salaries of forensic psychologists and $9.5 million for a new behavioral health crisis center in north Georgia. Tanner’s budget includes money for improvements to existing facilities, community- and jail-based restoration services, and “Project New Hope” at Georgia Regional Hospital — a transition program where people can receive vocational training and live after they find a job. It will be the first program of its kind in the state’s history.

Tanner added that DBHDD, Chatham County and Gateway Behavioral Health have come together to assign a forensic psychologist assigned solely to Chatham County. In the next 30 days, Tanner said, the contract will be executed, and the new forensic psychologist will start working.

DBHDD is implementing a 14-bed jail-based restoration program at the Chatham County jail, which will fund a full-time jail in-reach coordinator and a full-time forensic peer.

“Chatham County is going to be a model that all the other counties and cities across the state want to be like,” said Tanner. “They're going to be in excellent condition very shortly.”

Drew Favakeh is the public safety and courts reporter for the Savannah Morning News. You can reach him at AFavakeh@savannahnow.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Chatham County's mental health court faces critical backlog in services