How safe are Kentucky nursing homes? There are hardly any inspectors left to tell us

Fewer than one in five of Kentucky’s nursing home inspector positions were filled as of last October, according to a report released in May by a U.S. Senate committee.

That was the country’s highest vacancy rate for nursing home inspectors, leading to a massive work backlog and, as a result, overlooked hazards for elderly and ailing Kentuckians, the Senate Special Committee on Aging warned in its report, titled Uninspected & Neglected.

“Time is of the essence when state inspectors need evidence to prove serious deficiencies like physical abuse, sexual assault or inadequate medical care,” the committee chairman, Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pa., said in May. “My fear is that the trail is going cold for too many residents before nursing home inspectors can arrive on the scene.”

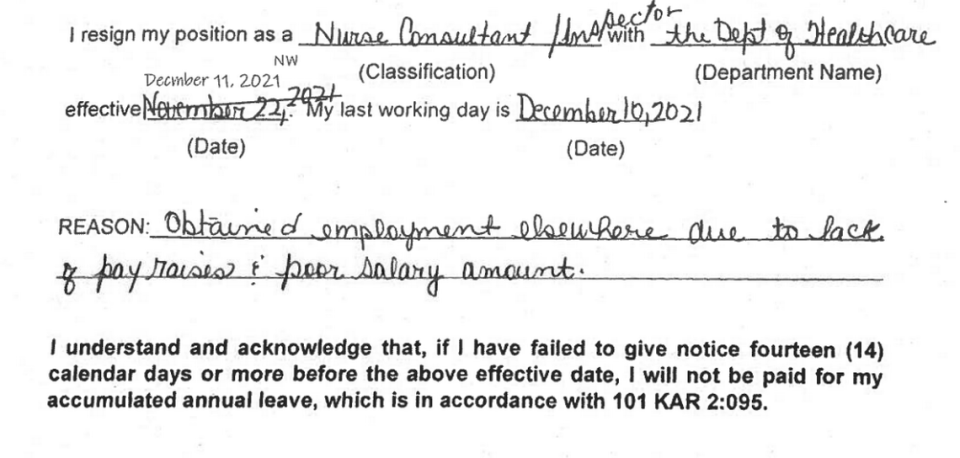

Interviews and a review of Kentucky nursing home inspectors’ resignation letters since 2021 show complaints about low pay and a lack of raises, as well as stress from long work hours and constant travel around the state.

Barbara Lear, a nurse, had worked as an inspector for less than a year when she quit last summer. Lear said the state was so badly under-staffed that instead of sending small teams of inspectors out to nursing homes for a one-week survey, as it’s supposed to, it sent nurses by themselves for surveys that could drag on for up to five weeks.

Lear, who lived in Hopkinsville, covered a territory that stretched hundreds of miles, from Mayfield in the west to Lexington in the east.

Many abuse and neglect complaints the inspectors reviewed were two or three years old by the time the state got around to them, so the residents involved often were dead and the employees had quit or been fired long ago, Lear said.

“How much success are you going to have investigating a three-year-old complaint?” Lear asked.

“I took the job to make sure things are getting done right and people are getting taken care of,” she said. “When that’s not what’s happening, it’s very frustrating.”

Inspectors said in their resignation letters that their duties were important but unappreciated. Pressure only grew worse as the rising number of job vacancies piled more work on the few who stayed, they said.

“I feel that surveying teams continuously sweep things under the rug that should be cited,” wrote inspector Melanie Richardson in her September 2021 letter. “No one is held accountable for their lack of regard for the population that we once strived to protect.”

“Not at all happy with this job or this administration. Very toxic environment,” wrote inspector Marilyn Klotz in May 2022.

The Office of Inspector General at the Kentucky Health and Family Services Cabinet is the agency responsible for annual “standard surveys” of the state’s 277 nursing homes. These multi-day tours are meant to catch deficiencies in care before residents can be hurt, sickened or killed.

Adam Mather, the cabinet’s inspector general, was a regional vice president at Signature HealthCare, owner of low-rated nursing homes around the state, when Gov. Andy Beshear appointed him in 2020.

Mather and other cabinet officials declined requests over two months to be interviewed for this story. The cabinet also declined to answer most of the questions submitted by the Herald-Leader about nursing home inspections and inspector vacancies.

In a brief statement, cabinet spokeswoman Susan Dunlap said the state is boosting the salaries of the job known as “nurse consultant inspector,” the registered nurses who lead nursing home inspection teams, in an effort to hire and retain more of them.

The nurses made about $50,000 a year in 2020, which is tens of thousands of dollars less than they could earn by leaving for a job in the private sector. Some departing nurses told their supervisors they were leaving for jobs that paid more than $100,000, according to state records.

After several raises and other incentives, some recently approved, the nurses were bumped to a salary range of $72,328 to $95,834 as of July 1, according to the cabinet.

“It is believed that the new midpoint salary will help with recruitment NCIs,” Dunlap said.

However, she added, most of the jobs are still unfilled.

“Staffing in this area currently shows 72 vacancies with 22 filled state positions,” she said.

Writing to the Senate committee last fall, Kentucky officials acknowledged that they’re missing the federal government’s deadlines for nursing home inspections. Staff shortages are to blame, state officials said.

“The DHC struggles to meet the above-mentioned federal workload priorities, while trying to maintain an adequate and effective workforce,” Melinda Beard, director of the state inspector general’s Division of Health Care, told the Senate in a letter last October.

According to the Senate report, Kentucky led the 50 states with the highest job vacancy rate for nursing home inspectors at 83 percent. Alabama came in second (80 percent); Idaho was third (71 percent). The average vacancy rate nationally was 29 percent, the committee said.

Low pay, little experience

Writing to the Senate committee last fall, Kentucky’s health cabinet said salaries for all its nursing home inspectors averaged $53,906, which was $21,000 below competitive market rates, especially for the registered nurses on each inspection team.

Other inspection team members include different kinds of medical specialists like nutritionists and pharmacists, who also can command better wages in the private health-care sector.

The few inspectors who remain on the state payroll tend to be inexperienced, the cabinet told the committee.

“Sixty-seven percent of our workforce have two years or less of surveying experience, which affects the quantity and quality of our work product,” Beard wrote. “So training is crucial for these staff. However, at this time, Kentucky’s five trainer positions are vacant.”

“Although we continue to post positions and conduct interviews routinely, once candidates are offered the position, they decline, citing the low pay,” she wrote.

“This leads to our need to re-post more positions, review more applications and conduct more interviews than we have ever had to do before, and (it) adds significantly to our daily workload. This also takes time away from our CMS work duties.”

Kentucky, like the other states, is required to inspect its nursing homes every year on behalf of the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS. Nursing homes rely on Medicare and Medicaid for their funding.

Kentucky’s nursing home industry says it’s not happy with the situation, either.

“We are concerned about the workforce shortages that the state survey agency is experiencing, because timely surveys, a transparent and fair process, as well as ongoing communication between surveyors and providers, are of the utmost importance,” said Betsy Johnson, president of the Kentucky Association of Health Care Facilities.

“We are, however, understanding of the state survey agency’s plight and we know that they are working diligently to address their workforce shortage,” Johnson said.

Hiring outside help

Apart from low pay, inspectors also cite burnout from constant travel and long hours as reasons for quitting, the cabinet told the Senate committee. Federal rules require that at least 10 percent of standard surveys be conducted “off-hours” — on weekends, early mornings, late nights or holidays — to get an accurate look at quality of care.

So the nurses and others weren’t just working for substandard pay as inspectors, they were spending weeks away from their homes and families, living in hotel rooms. When they’re not walking through facilities, inspectors stay up late at night to fill out reams of mandatory paperwork.

“When I took the job, it was with the understanding that I would be away from home a lot, but it would be three or four days a week,” said Lear, the Kentucky nursing home inspector who quit last summer. “Instead, because I was by myself most of the time, I was working five to seven days a week.”

The cabinet reported 79 inspector vacancies in October, 57 of them for registered nurses.

As a partial stopgap, Kentucky has — like 25 other states struggling with a backlog — turned to privatization.

Kentucky awarded a nursing home inspection contract to one of the three for-profit nursing home inspection companies that employ their own teams of nurses and other medical specialists. Last year alone, these companies collected nearly $20 million from the states.

Kentucky selected CertiSurv, based in Columbia, Tenn., giving it a two-year, $1.8 million deal in 2021 that came with optional renewals. For each Kentucky nursing home that CertiSurv inspects, it’s paid between $22,750 and $29,475, depending on facility size. That’s close to half of what a state inspector was earning in a year’s salary.

But this has barely dented Kentucky’s backlog. By the end of 2022, CertiSurv had filed standard survey reports for about two dozen nursing homes around the state, according to CMS data. It filed six more reports during the first two months of 2023.

A priority or not?

Kentucky’s state and federal funding for nursing home inspectors has remained stagnant for the last five years, at about $1.4 million and $5.2 million, respectively.

The Senate report called for a boost in federal funding. A plan by Democratic President Joe Biden to spend $500 million more on nursing home inspections nationally — a nearly 25 percent increase — ultimately went nowhere in the politically divided Congress.

Dunlap, the state health cabinet spokeswoman, told the Herald-Leader that Eric Friedlander, the state’s health secretary, made lawmakers aware of the problem of inspector vacancies in his testimony to a state legislative committee in July 2022.

A video of the Frankfort hearing shows Friedlander speaking for about one minute on staff shortages at the inspector general’s office during a 90-minute review by lawmakers of his cabinet’s overall operations.

“We are understaffed in the inspector general’s office,” Friedlander said at the hearing. “I will tell you, you know, we are competing for nurses, too. We are competing for inspectors. And it’s a challenge to recruit.”

However, House and Senate leaders who oversee funding for the health cabinet say that, those brief remarks aside, it was news to them that a massive backlog exists in Kentucky nursing home inspections, or that the Beshear administration is searching for ways to hire and retain more inspectors..

State Rep. Danny Bentley, R-Russell, is a pharmacist who runs the House budget subcommittee for health and family services.

“Neither Rep. Bentley nor (House) leadership have any records or recollection of the cabinet asking for additional funding for nursing home surveyors at the cabinet’s OIG,” spokeswoman Laura Goins said. “This also applies to ongoing conversations about the two-year budget they are deeply engaged in crafting now.”

Theresa Hutchins, whose uncle died in 2021 during a nearly four-year stretch between so-called “annual” inspections of a Louisville nursing home, is suing that facility for wrongful death and corporate negligence.

Hutchins said Kentuckians would not for any reason tolerate a lack of health inspections at child-care centers or restaurants. Children are deeply valued, she said, and everyone eats at restaurants.

But there is far less concern shown for government oversight where the elderly live, Hutchins said.

“The truth is that we discard our seniors. We don’t treat them like they’re important at all to our society,” she said. “It’s really sad.”