A fight over a stalk cutter in 1922 turned into a mass exodus of Black residents of Jay

Reader warning: This story includes a reference to signs containing an offensive racial slur toward Black people, as part of more extensive reporting about historic discrimination practices in Florida towns.

One hundred years ago, a Black man named Albert Thompson was sitting in a solitary jail cell at Fort Barrancas awaiting trial for the alleged murder of a white man named Sam Echols.

Today, the incident is almost totally forgotten, but evidence is coming to light that it was the spark of what appears to be the forced removal of at least 175 Black residents from the Jay area of northern Santa Rosa County, which would leave a legacy of Jay as a “sundown town” with the implied threat of violence for any Black man or woman who found themselves in area of Jay after sunset.

Two Florida cities, two paths: Former ‘sundown towns’ grapple with their pasts

What is a 'sundown town'?: When and where American racism was in full public view

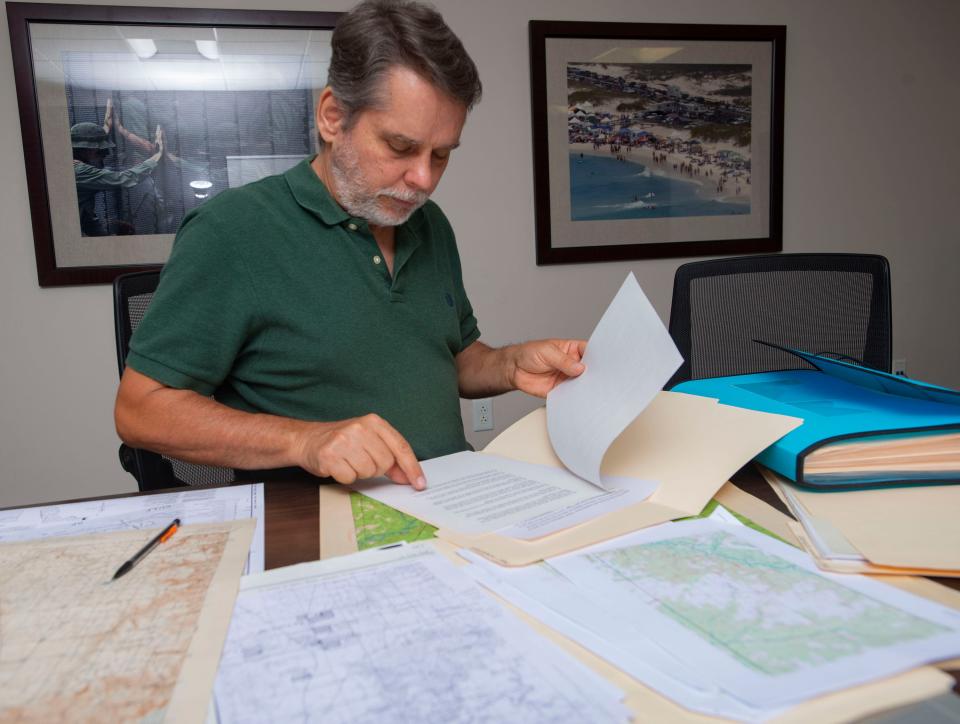

Pensacola historian Tom Garner has been researching the Thompson-Echols shooting and its aftermath for 15 years and has documented compelling evidence that Black residents of the Jay community were driven out of the area.

Census records document 175 Black residents in the Jay area in 1920. In 1930, zero Black residents were counted.

Garner revealed to the public in 2020 that T.T. Wentworth Jr. was a leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Pensacola. Garner was also a founding member of the Pensacola Archaeological Society and the person who identified the locations of two lost Spanish colonial settlements in Pensacola.

Garner said he believes the killing of Echols was the turning point for north Santa Rosa County that led to a forced mass exodus of Black residents.

Over the next 50 years, Jay was open about its “sundown” status.

Garner has documented oral history accounts about signs around the town that said “N-----, don’t let the sun set on you in Jay.”

In recounting the narrative Garner doesn’t shy away from the use of the racial slur when quoting the sign, arguing that using a euphemism softens the impact of the history.

“I think people need to be shocked,” Garner said. “I think they need to hear exactly what was said and what was done. I don’t think we need to soften it in all situations. I want people to understand exactly what happened, and just how vile and brutal these words and actions were. We in the white community don’t understand how bad it was, and we need to. Softening it will not help that understanding.”

A fight between Santa Rosa County farmers: What happened in 1922?

Garner has worked to gather court records and contemporaneous newspaper accounts in the Pensacola Journal and Milton Gazette to piece together a narrative of what happened.

Thompson was a married man with two children who had been farming for years in Santa Rosa County, renting land from Escambia Land and Manufacturing Company that was owned by the Pace family.

Thompson appears to have been a successful farmer. He owned a stalk cutter, a piece of equipment pulled by a mule, used to clear a field before the spring planting season.

It was the morning of Feb. 24, 1922, when Echols, along with his friend Joil Yarber, approached a farm owned by another Black farmer, Henry Daniels.

Thompson and Daniels were there, and Echols wanted to use the stalk cutter. Thompson told Echols he would have to come back another day as it was already promised for someone else.

Echols ignored Thompson’s objections and started hooking up the farm equipment to his mule. By Yarber’s account, Thompson began unhooking the mule, cursing at Echols. Echols then came up to Thompson and pulled Thompson’s tobacco pipe from his mouth, throwing it to the ground.

Thompson would later testify he was being held by Yarber as Echols beat him with an iron bar from the cutter. Yarber would say Thompson attacked Echols and Yarber intervened to protect his friend.

During the struggle, Thompson pulled out a pistol and fired several shots, striking Echols three times. Thompson immediately fled the scene. Echols would die of his wounds the next day.

“Thompson takes off because you got to figure he’s scared of being lynched,” Garner said.

A lynch mob had murdered Bud Johnson, a Black World War I veteran who was accused of raping a white woman, just three years earlier by burning him at the stake, likely somewhere in northern Santa Rosa County. However, at least one eyewitness told an NAACP investigator that Johnson was killed in 1919 for his recently deceased father’s land, a 27-acre plot in Jay.

Twelve people were lynched in Milton: Their lives are finally being honored

After the murder of Echols, articles in the Milton Gazette portray a white public in Santa Rosa County outraged at his killing.

Thompson was soon captured by a posse of men and the Santa Rosa County Sheriff and taken back to jail in Milton, later being transferred to Pensacola amid concerns a lynch mob was forming. The Escambia County Sheriff also worried about a lynch mob and took Thompson to the Navy base, putting him under federal protection at Fort Barrancas.

The trial, verdict, and Thompson's life after conviction

While the Milton Gazette continued to write articles calling Thompson a cold-blooded murderer, Thompson had prominent supporters in the white community.

John C. Pace, whose family owned the property Thompson’s farm was on and would later would be involved with founding the University of West Florida, wrote a column in the Pensacola Journal in the days after the murder arguing Thompson had been acting in self-defense and was a “quiet and peaceful negro.”

Thompson also had prominent attorney John Clay Smith defend him. Smith would go on to represent Pensacola in the Florida Legislature.

Smith sought and won a change of venue for the murder trial to Escambia County.

As part of that effort, Smith cited that Thompson was unable to contact any witnesses who may help his case as all of the Black residents were being forced to move.

“... All of the colored people, many of whom were witnesses to the unfortunate occurrence, were advised, directed, ordered, and made to leave that section," Smith wrote.

Thompson was convicted of second-degree murder by an all-white jury.

Garner notes this is an interesting verdict for 1922 involving the murder of a white man at the hands of a Black man. A conviction of first-degree murder would have carried the death penalty, but the jury went for the lesser charge.

The Milton Gazette decried the verdict in its coverage of the trial.

Thompson was given a life sentence, but state prison records show he only served six years before his sentence was commuted. It’s unclear why his sentence was commuted but the next record of Thompson gives an indication that the Pace family never gave up on him.

Thompson became a butler and chauffeur for John Henry Pace, uncle to John C. Pace, at his home in Jacksonville, according to that city’s records.

Garner said it’s possible the Pace family used their political connections to win Thompson’s freedom. Records show that Thompson and his wife remained employees of the Pace family until their deaths in the 1930s.

“You don’t take somebody into your household as a butler and a chauffeur if you think he’s a cold-blooded killer,” Garner said.

Historical records show hints of an exodus

Census records would later show that 175 Black residents had lived in the Jay census district. In 1930, that census district had been expanded but now the number of Black residents was zero.

In a book of collected memories of J.C. Franklin, who was born in 1914, Franklin recounts his memories of growing up in Jay. Most of the 21-page document published by the Jay Historical Society are descriptions of images of nature, farm life and growing up in rural Florida. Then, like a discordant note, one sentence sticks out of the rest of the imagery like it must have when Franklin was an 8-year-old boy.

“A Negro killed a white man over the use of a stalk cutter and all the blacks were moved from the area,” Franklin wrote.

Jay was incorporated as a town in 1951.

Garner had recorded several oral histories of signs being up around the town during the 1950s and 1960s, but with the discovery of oil near the town, it appeared that by the early 1970s the signs had come down as the town was beset by oil workers and state and national reporters who noticed the lack of Black residents.

A 1971 report in the Tampa Bay Times, a reporter cited an unnamed Black preacher in a nearby town who recounted that 50 years earlier a Black man had killed a white man.

“Tempers ran hot and by sunrise the next day, Jay was without Negroes,” the report said. “He said he heard the story from an old black woman who walked with a limp after mules bolted during the exodus and a wagon ran over her leg.”

A 1974 article, also in the Tampa Bay Times, noted the lack of Black residents and quoted the then-mayor of Jay, J.D. Bray.

“The sun doesn’t set on a colored man in Jay,” Bray says. “Come 4 o’clock, they’re gone. They were run out of here back in the days of the turpentine still. And they know better than to come in here.”

Another article in the Fort Lauderdale News in 1985 reporting on the oil boom in Jay again noted the lack of Black people in the town, quoting an unnamed elderly patron of the Kountry Townhouse diner.

“They don’t let the sun set on them in Jay ... ain’t had no colored living here since 1922,” the elderly man said.

Journalism Matters. Your Support Matters. Subscribe to a local Florida publication today.

Jim Little can be reached at jwlittle@pnj.com and 850-208-9827.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: The forgotten story behind Jay's ‘sundown town’ legacy