Fighting a double war: a Black journalist in WWII

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There is news, and news.

A celebrity sighting is one kind. A nation in default is another. But the most urgent news of all, the ultimate News You Can Use, is the news that literally hits home. Where is my son?

That's the kind of news that Ollie Stewart could — sometimes — bring to anxious folks back home.

For that, Stewart and the other war correspondents of World War II — and all correspondents in all wars — earned an esteem that is rarely granted to reporters.

"Tears filled the eyes of Mrs. Carter, 27 N. Peach Street, when told that Ollie Stewart, AFRO war correspondent in Africa, had seen and talked to her son, Sgt. James H. Carter," reads one account from the time.

By the war's end, Stewart was known to many thousands. People crowded around him and asked for his autograph when he did public speaking engagements. “Now I know how Joe Louis or Clark Gable feels," he said.

From the front

Matters of Fact | A column about our lives in the age of media

With Memorial Day around the corner, it's worth considering the role that journalists have played in wartime.

The names are legendary: Ernest Hemingway, Winston Churchill, Margaret Bourke-White, Edward R. Murrow, Walter Cronkite, Michael Herr. So is the courage that was sometimes demanded of them. Ernie Pyle, the most famous World War II correspondent, was killed in 1945 at the Battle of Okinawa. Many others did not outlive the conflicts they covered.

But there is courage, and courage. Ollie Stewart's was of a special kind. He was African American — the first Black reporter accredited by the War Department. This, at a time when the military was still segregated, when Black folks — journalists or no — were expected to know their place. Stewart walked a tightrope.

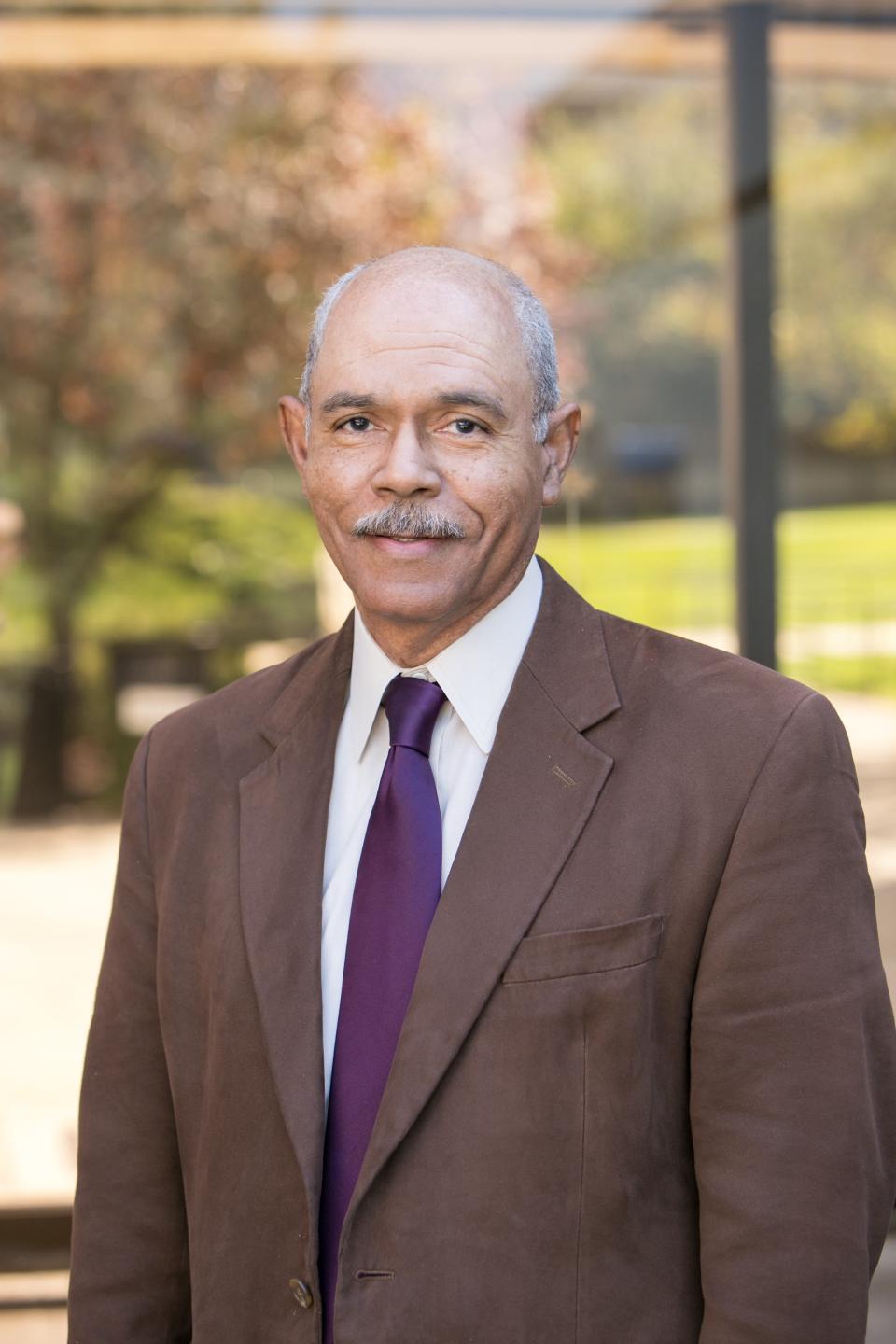

"He understood his role and timing," said Larry Greene, a professor of history at Seton Hall University, who will be hosting a program called "Fighting On Two Fronts: Black GIs in World War II and Ollie Stewart's Reporting in the NJ Afro-American," co-sponsored by NJPAC and the Newark History Society, on May 23 at 6 p.m. at the Newark Public Library. Admission is free; the presentation will also be livestreamed.

The New Jersey Afro-American — published in Newark — was one of a chain of Black-owned and edited papers, founded in 1892, and still based in Baltimore. At its height, it published a dozen weekly papers (the New Jersey edition no longer exists).

"We just celebrated 130 years of continuous operation," said Savannah Wood, great-great-granddaughter of the founder, and manager of the archives.

Community news, church news, social events, sports, Black achievement in all areas — that was the stuff that the Afro-American, the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier and hundreds of other Black-owned papers brought to their readers. News that was invisible to The New York Times.

For Black readers, especially during the Great Migration, these papers were a voice — and a lifeline.

"It was one of the ways people stayed in touch with where they came from," said Paterson historian Jimmy Richardson, who has written for several such papers.

"As a migrant coming from the South, that's how you kept in touch with the hometown team," Richardson said. "Also the national news going on in the Black Community."

Our roving reporter

Black papers also editorialized, and investigated. Which is how Stewart, originally from Louisiana and schooled partly in East Orange, made a name for himself.

"He started out as a sportswriter, and then he's given the task by the owners of investigating the plight of African American soldiers in the basic training camps in the South," Greene said.

Anyone who's seen "A Soldier's Story" will have an idea of that plight.

"There was a lot of anti-Black harassment and violence directed against Black soldiers in the training camps," said Greene, who has taught courses on African American history, the Great Depression, World War II and related subjects. "Stewart traveled through the South, talking to Black soldiers."

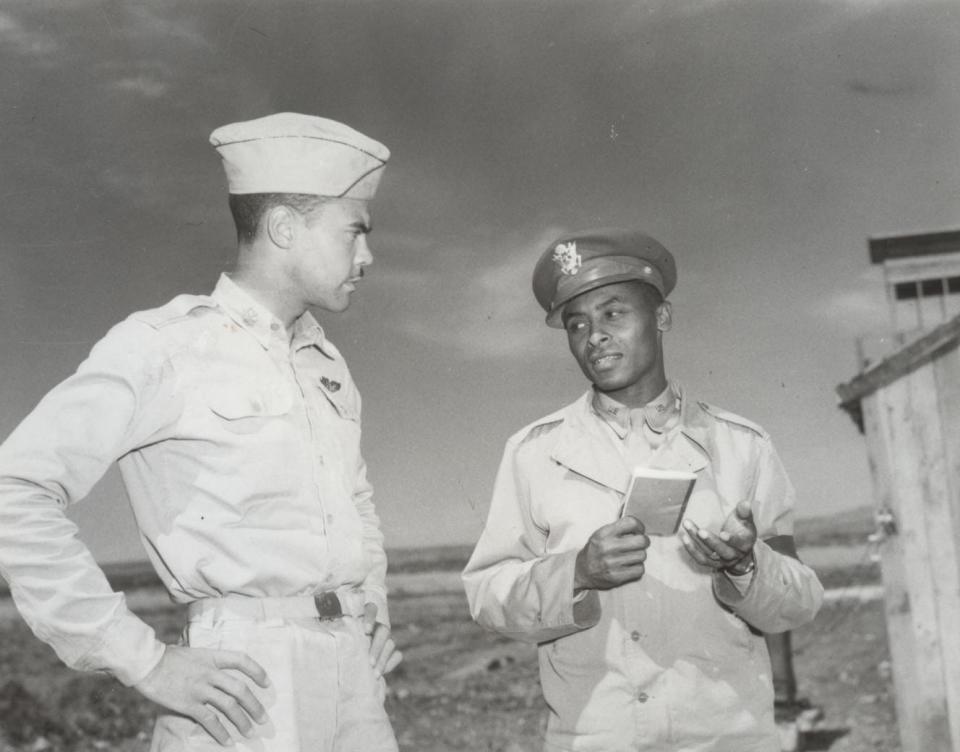

Once World War II broke out, Stewart — and his editors — pushed the government to designate Black war correspondents. Such reporters had special access. They had a uniform and an Army rank and traveled with the troops.

But first, they needed to be credentialed. Something the government was not willing to do, at first. Indeed, there were some who wanted to get rid of Black newspapers entirely, as a wartime measure.

"J. Edgar Hoover wanted to eliminate them," Greene said. "He made a number of attempts. And certain elements of the military wanted to ban African American newspapers from Army posts."

Hoover had his reasons. Some in the Black press had been critical of the war effort. A war against Nazis, fought by a segregated army, was not an irony they were willing to let drop. Moreover, the memory of the last war lingered.

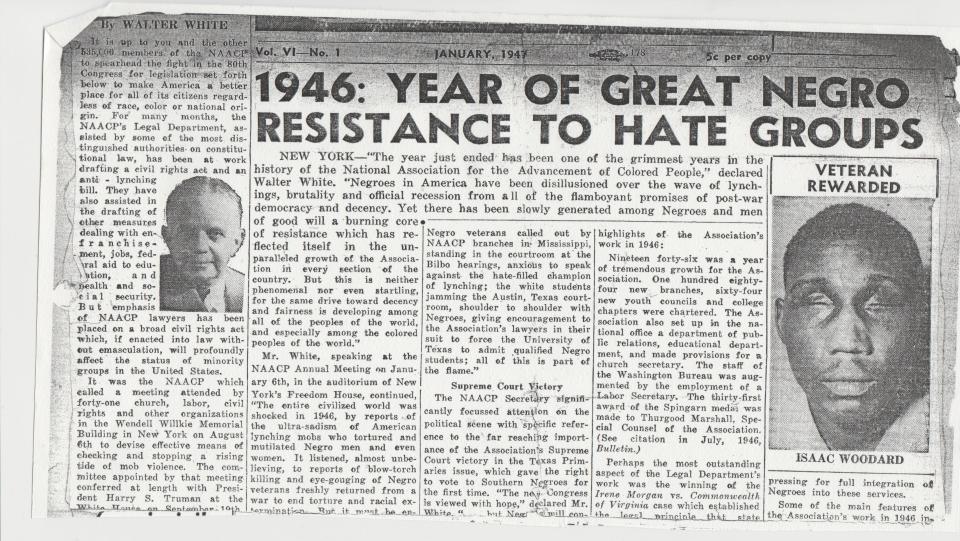

Black soldiers who had fought bravely in regiments like the 369th Infantry ("The Harlem Hellfighters") and thought they'd clinched their case for full citizenship came home to the same racism and abuse. And here was the government, asking them to do it all again. "Essentially the African American press was calling the country out on the hypocrisy," Greene said.

In the end, Attorney General Francis Biddle overrode Hoover. Black journalists, starting with Stewart in 1942, would be credentialed to cover the war. Under certain conditions.

They would need to accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative. Good news about Black achievement, yes. Racism in the armed forces, no.

That was the bargain Ollie Stewart made. And kept — with misgivings.

Choosing his words

"Stewart bit his tongue, in my opinion," Greene said. "It isn't that he didn't recognize the injustice he saw. For example, when he covers North Africa, he doesn't talk about the fact that he's a victim of discrimination himself. When he lands, all the white officers in charge don't want him to bunk with the other white correspondents. He doesn't write about that. Much later on, he will talk about that."

Nor does he touch topics like the segregation of the blood supply, or the way Black troops tended to be relegated to secondary roles like trench digging and truck driving (which could, however, be just as dangerous as combat).

But Stewart also had a second — implicit — understanding, Greene said. With his own editors.

He would send back his upbeat dispatches from the front, yes. Meanwhile, the paper itself would continue to investigate and editorialize against racism. The one-two punch of Black heroism at the front, set off against outrages at home, would lead — this time — to changes after the war. So it was hoped.

"That was the Double V campaign," Greene said. "Victory over fascism abroad. Victory over racism at home."

That was how Stewart understood his mission, as he went to war. England first, then North Africa in the latter part of 1942, Italy in 1943, back to the States, London again in May of 1944, then France.

He was in Casablanca for the 1943 conference — at the same time the fictional Sam was playing "As Time Goes By" for the fictional Monsieur Rick. He was on Omaha Beach a month after the first wave of landings. He was on the ground at the liberation of Paris. In fact, he was very nearly a casualty. "There were some snipers left over in Paris, and they were shooting," Greene said. "He's ducking snipers."

And he did send back stories of uplift. He wrote about the Tuskegee Airmen (not yet so-called), and the Barrage Balloon Battalion, manned by African Americans, that landed on D-Day.

"The beach was the scene of beehive-like activity as I left, with a colored barrage balloon outfit commanding a series of silver balloons protecting ships, which are constantly coming and going, from dive-bombing enemy planes," he wrote from Normandy.

For readers, though, the stories that meant most were the personal ones.

"His reports often ended with a simple list of soldiers he had encountered in the field — a collection of names, ranks and hometowns that buoyed family members back home," Marc Lancaster wrote on the website World War II on Deadline. "The paper routinely published stories in which parents expressed their gratitude for Stewart passing along word of their sons."

Back to the future

All very edifying. But when Stewart came back, after the war, he found that things had not changed. The same menial jobs, the same insults, the same segregation.

And as had happened after World War I, there were race riots: in Columbia Tennessee in 1946, in Chicago in 1947, in Peekskill, N.Y., in 1949. Once again, African Americans who'd had their expectations raised in Europe had to be taught "their place."

"I think he becomes embittered covering the post-war discrimination," Greene said. "It leads him to emigrate."

Stewart settled in Paris, in company with a number of other Black expatriates — Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Josephine Baker. But he continued to write for the Afro-American until the year of his death: 1977. "He opened Afro readers up to the world he lived in, abroad," Wood said.

Meanwhile, the changes he'd worked for, and despaired of ever seeing, began to happen after all.

In 1948, the U.S. Army was desegregated. In the 1950s, the civil rights movement gathered steam. And it happened, not least, because of veterans. The people whose lives Stewart had been sharing with his readers.

"If you go to Montgomery, the bus boycott, you will find there are a lot of veterans involved in that," Greene said.

Not only veterans, but the fathers, brothers, wives, sons and daughters of veterans. People who had read Stewart, and other war reporters, in papers like the Afro-American. People well aware of what their relatives had done, overseas. People who knew what they were owed.

"They had been reading about the war in the newspaper," Greene said. "When it's over, there is this sense that African Americans had made their contribution to the war effort. They're saying that the time had come, the time for a full push for civil rights. They felt emboldened."

All great war correspondents — to use the classic phrase — "bring the war home." But Stewart, maybe, more than most.

"I think we owe a debt to all the African American war correspondents," Greene said. "They were able to make a case for the entitlement to citizenship."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Pioneering Black journalist fought two wars