Fighting to prevent overdoses in pregnant women, new moms: What's working in New England

Megan LaChapelle gently placed her 3-month-old son in a baby bouncer on the floor. He was dressed in a cozy onesie with dinosaur feet, wearing fleece gloves to keep his little hands warm in the middle of a New Hampshire winter.

LaChapelle named him Karter, in honor of her grandfather. Though he spelled it with a C, she was sure to note.

The 28-year-old is spirited in how she speaks, enamored by her son and excited by her new life − one where she's getting back on her feet at Hope on Haven Hill, a nonprofit residential facility in the city of Rochester for pregnant women and new mothers who are battling opioid addiction.

"Look at you," she said affectionately. "I can't believe you're here."

LaChapelle was in jail when she gave birth to him. An injection drug user, her struggle with substance use started years ago with alcohol. Then came heroin, then came meth. Pregnancy was hard. She relapsed a couple times.

"This is the first time in my life I've ever been sober," LaChapelle said on a recent January evening while her housemates gathered hectically for dinner around a large wooden table. Round bellies moved around the shared kitchen while babies were fed with bottles.

Drug overdose deaths in pregnant women, new moms have increased

New research shows the number of pregnant women and new mothers dying from drug overdoses reached record highs during the COVID pandemic. The study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in December, looked at more than 7,600 death certificates of people who died while pregnant or had just given birth between 2017 and 2020. During that time, the number of overdose deaths in the group doubled, the study found, and most were caused by fentanyl.

Investigation:We have a cure for hepatitis C. Why are hundreds of New Englanders still dying every year?

Drug overdose deaths are up overall nationally because of the continued spread of fentanyl and the treatment, health care and social connections disrupted by the pandemic. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows nearly 107,000 Americans died as a result of a drug overdose in 2021, an increase of nearly 16% from 2020.

Experts say pregnant women and new mothers are a particularly unique population facing increased stigma and barriers to treatment.

"It's devastating," said Kerry Norton, executive director and co-founder of Hope on Haven Hill. "After you’ve had the baby, for folks that aren’t in a program, the risks are overwhelming. Specifically for women that leave treatment prematurely. They’re the folks we worry about the most and the folks we have lost. That’s crushing."

New England states are trying to reduce maternal health deaths

All six New England states have maternal death review committees that probe every death of a pregnant or postpartum person as a mechanism to learn more and hopefully reduce such deaths in the future. Trying to combat opioid-related maternal deaths are programs like New Hampshire's Hope on Haven Hill that work with expectant and new mothers on treatment, case management, housing and more. Across New England, similar programs are fighting the same fight.

In Vermont, opioid use among pregnant women was the highest in the country even prior to COVID, per CDC numbers from 2018. Addressing substance use deaths in pregnancy and postpartum was "identified as a priority for the (state) Department of Health," according to a report issued in 2019.

Ilisa Stalberg, director of maternal and child health at the Vermont Department of Health, said that's a commitment the state has recently renewed.

"The connection to families was fractured during the pandemic," Stalberg said.

2021 data:Nearly 107,000 drug overdoses, COVID deaths, push US life expectancy to lowest in 25 years

Vermont, like all states, is "rebuilding infrastructure" that fell apart during COVID, like home-visiting programs that were able to gauge mother and child wellbeing, and intervene if necessary.

With locations in Fall River, Massachusetts, and Cranston, Rhode Island, SSTAR provides both addiction treatment and a residential program for pregnant and postpartum women grappling with substance use disorders. Dr. Genie Bailey, an addiction medicine specialist in Fall River, said the stigma for these women is very real.

"If you're making it such that women fear coming into treatment because of incarceration or losing their baby, they're more likely to die," Bailey said. "Treatment isn't a mark of shame, treatment is a mark of integrity. (The woman) has proven she wants to have a successful pregnancy and she wants to have this baby."

Hope on Haven Hill is one way New Hampshire is trying to extend postpartum support for mothers

Norton recalled the last maternal death review she partook in. Tears came to her eyes as she told the story of a young woman who was a "super awesome good mother" to a baby girl she'd given birth to at Hope on Haven Hill. Her life had been a whirlwind of trauma, but she was engaging in treatment and working hard with her support team after being released from jail.

But as soon as her probation requirements ended and the New Hampshire Department of Children, Youth and Families closed her case, she wanted to leave the program against medical advice. She died shortly after that.

In New Hampshire, from 2017-2020, 62% of pregnancy-associated deaths were due to opioid overdoses, data shows.

"Specifically, people are dying in that 7-12 months postpartum," said Jessica Bacon, a midwife at Hope on Haven Hill. "The visits go away, family supports go away, people discharge and that’s when they need the support the most, in that whole first year."

Hope on Haven Hill operates two residential facilities and outpatient services. The high-intensity program, where Megan LaChapelle currently resides, is a country farmhouse where women live with their babies, partaking in treatment, wellness practices and parenting classes. Norton said the model works. Last June, the nonprofit broke ground on a new 8,000-square-foot facility, set to become a "hub" for families.

Hope on Haven Hill was LaChapelle's one shot to keep her son after leaving a Florida jail, she said. A New Hampshire native, she's been in the program for two months and feels herself transitioning, gaining new skills every day.

"I'll use all of these skills because of him," she said, looking at her son, "and I have those skills because of this place."

In the living room where she talked, an arts and crafts project reading "hold on, pain ends" is taped to the wall.

While Hope on Haven Hill prides itself on being a nurturing and accepting environment, the outside world isn't that way most of the time for these women, both Norton and Bacon said. Even within the recovery community, they're stigmatized.

Historically, said Bacon, prenatal care providers have been uncomfortable talking about substance use treatment with patients, an issue requiring education in hospitals and health care systems. Medication-assisted treatments, like buprenorphine and methadone, have both been shown to be safe and effective treatments for opioid use disorder during pregnancy, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

But some providers are still reluctant to prescribe them — due to worries about harming the developing fetus — or even engage in conversation around drug use and pregnancy.

According to the state's 2022 annual report on maternal mortality, New Hampshire has developed harm reduction education in each birthing facility "to reduce risk of postpartum relapse and potential for overdose."

4 ways Vermont is 'prioritizing' reducing overdose deaths in pregnancy and postpartum

Several initiatives are underway to address what has been a long-standing reality in Vermont — high rates of drug use during pregnancy and early parenting, and high rates of children born with opioid exposure.

In 2021, the Vermont Department of Health reported the highest number of fatal opioid overdoses ever recorded in the state.

Vermont's overdose problem:Overdose deaths in Vermont soared by 70% amid COVID. It's the highest increase in the US.

"In the last year coming out of COVID, we have reprioritized this topic and are having a multifaceted approach," said Stalberg, the state Department of Health's director of maternal and child health. Parts of that approach include:

The Vermont Perinatal Quality Collaborative, a partnership mobilizing state networks to better pregnancy and infancy outcomes by improving care for mothers, babies and families.

State participation in a policy academy run by the National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare, looking at the intersection of public health, clinical medicine, child welfare and the judicial system − and how those players can work together more effectively to support families.

A new initiative called "DULCE," a national evidence-based program involving pediatric health care and early childhood services promoting the healthy development of infants and support to their parents during the first six months of life.

A campaign called "One More Conversation," encouraging open dialogue between pregnant women and their health care providers about drug and alcohol use.

One Vermont program has received national attention. Based in Burlington, the long-standing CHARM program, housed in the KidSafe Collaborative, connects pregnant women and new mothers with a history of opioid use to coordinated prenatal care and treatment. CHARM was featured as a successful case study in a report by the National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare.

"Over a 16-year period, the extraordinary commitment of the CHARM Collaborative to a cross-system approach in working with pregnant women with opioid use disorders and their infants has resulted in improvements in practice and better outcomes for clients," the report reads. "The initiative has made possible the provision of a full range of services to families in half of the state of Vermont."

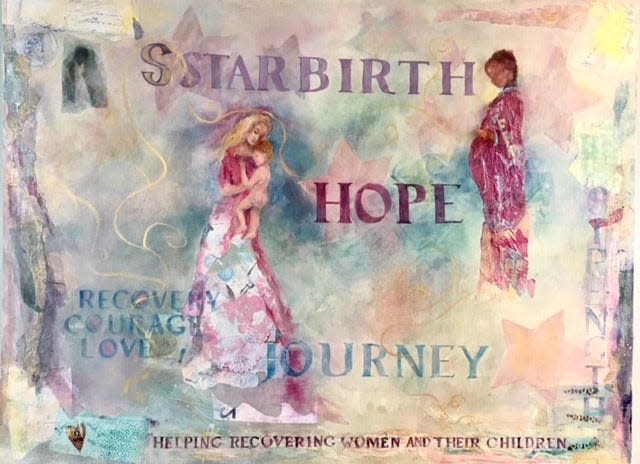

SSTARbirth in Rhode Island: Small program with 'huge impact'

Diane Gouveia has been at the helm of SSTARbirth for many years, the only licensed facility of its kind in Rhode Island. She's witnessed firsthand the guilt and shame so many women carry with them through the doors of the small residential program.

"Everybody says, 'Why are you doing this?' They immediately think if you're pregnant, you should want the baby and you should be able to stop what you're doing."

SSTARbirth calls itself a family reunification program where, like Hope on Haven Hill, women participate in treatment with their young children present, something Gouveia said is a huge motivating factor. In operation since 1994, the six-month program has a completion rate around 70%.

"We are really creating a safe, nurturing, loving environment," Gouveia said. "Women don't recover alone. Women need supports, women need peers. That feeling they're worthy of."

Rhode Island is one of 13 states, along with Vermont and Maine in New England, where the CDC has an OMNI team, which stands for Opioid Use Disorder, Maternal Outcomes and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Initiative.

The initiative is a "learning community" of sorts sharing strategies and best practices for improving the identification and treatment of pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder, and infants prenatally exposed to opioids.

Police, addiction specialists team up:A beacon of HOPE amid RI's opioid crisis

The Rhode Island OMNI team implemented a neonatal abstinence syndrome pilot program into First Connections, a free home-visiting program housed in the state's Department of Health. The goal of the pilot was to ensure women whose babies are born exposed to opioids have postpartum care following hospital discharge, with a First Connections nurse serving as a point person for services, appointments and other supports.

"I do believe there's been progress made at the birthing hospitals here in Rhode Island in regards to efforts made by medical professionals," said Gouveia, who noted many of these women don't seek health care during their pregnancies, worried that the discovery of their drug use will backfire. "Our experience is that you have to make it as safe as possible for people to feel like they can come in."

Gouveia said the program sports "wonderful and beautiful success stories" over nearly three decades.

"It doesn't happen all of the time, but it happens enough to remind us that the work we're doing is very valuable and that you touch lives," she said. "A program such as this has a huge impact. Often it's after the fact (women) realize how important their time at SSTARbirth was to them."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: How New England is fighting overdose deaths in pregnancy, new moms