Fights in Fort Worth when JFK was shot: “A white guy ... said ‘I’m glad he’s dead.’ ”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

An hour after Air Force One lifted off from Fort Worth in 1963, President John F. Kennedy was dead.

For the Fort Worth airmen at the center of America’s Cold War defense effort almost 60 years ago, a fight was beginning.

“A white guy turned off the TV and said ‘I’m glad he’s dead,’ “ remembered Rodney Hurst, then an airman in the Carswell Air Force Base honor guard for Kennedy and later a Florida civil-rights activist and leader.

“That started it. There were bloody noses everywhere — fights in all the halls — white airmen saying, ‘Good.’ “

Hurst and the honor guard had just stood and saluted as the president and first lady Jacqueline Kennedy greeted military families and children before boarding Air Force One to Dallas Nov. 22, 1963.

Now 78, he remembered that day last week by phone and also in a recent interview for the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas.

From discharge in Texas, he returned home to Florida, where he already had been among civil-rights activists targeted by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1960 Jacksonville white race riot known as “Ax Handle Saturday.”

He was stationed here from 1961 to 1965 as part of an early-day computer training program for the B-52 and B-58 bombers stationed at what was then a Strategic Air Command defense base. (It’s now Naval Air Station Fort Worth.)

Hurst knew Texas didn’t support Kennedy.

“I did not see Fort Worth as being a progressive community,” he said.

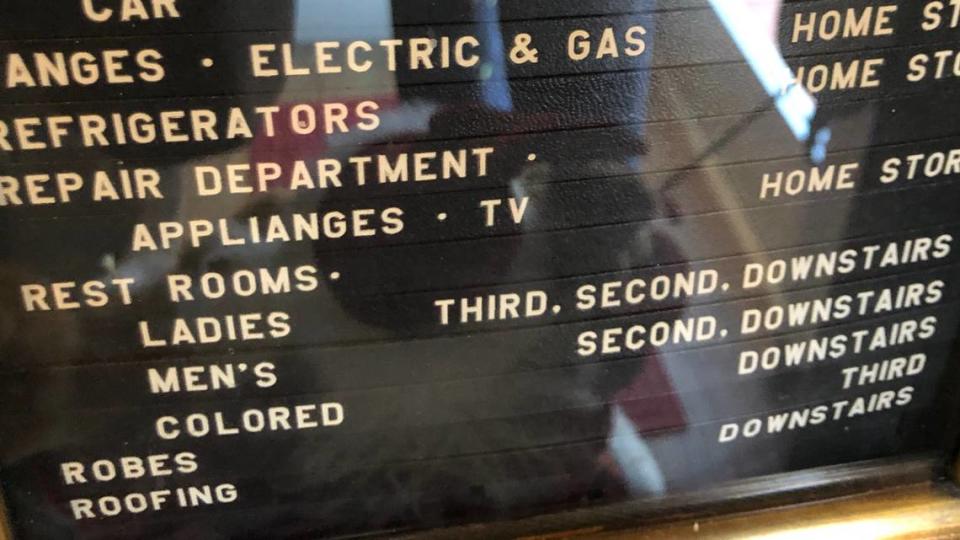

In 1963, public schools and city buses were still segregated. The last “white” and “colored” signs on toilets and water fountains had come down just before Kennedy’s visit.

If you thought the Air Force or Carswell was better — it wasn’t.

“The military just reflected what America was like in those days,” Hurst said.

“There was tension over civil rights,” he said: “I was housed with white men from rural Texas who bragged about being in the Klan.”

Hurst’s name made the Star-Telegram while he was at Carswell. He was a championship bowler.

But one of the other top bowlers’ first and last name began with “K.”

“He had a bowling shirt made with ‘KKK’ on it and wore it whenever I bowled,” Hurst said.

When Kennedy was shot down in Dallas after a happy visit to Fort Worth, the city staggered along with the nation in shock.

In the Sixth Floor interview, Hurst described sitting with other Black airmen at Carswell and staring at TV pictures of familar Dallas landmarks such as Dealey Plaza and the Texas School Book Depository’s Hertz billboard.

There was “just the anger, the sadness,” he said.

But not to some white airmen.

“We had fights in my barracks ... where there were lots of bloody noses and black eyes and abrasions and persons pushed down stairwells. I mean, all this on an Air Force base,” he said.

At one point, Black airmen were sent to their barracks for safety, he said.

“You were dealing with a very segregated American society,” he said.

Black Americans were skeptical but trusted Kennedy because he “said the right things and did the right things” for civil rights, Hurst said in the Sixth Floor Museum interview.

Hurst also remembers specific touchstones of his life in Fort Worth: Jacksboro Highway clubs; military-themed bars like the Missile Club on Evans Avenue; trips to Leonards Department Store downtown; and going to pro football games on a military discount to see Dallas Cowboys star and Jacksonville friend Bob Hayes in the Cotton Bowl. There were also trips to see the Dallas Texans, later the Kansas City Chiefs, in practice games at Farrington Field.

At a community event and again at segregated I.M. Terrell High School near downtown, he specifically remembers meeting a young Fort Worth civil-rights activist, Opal Lee.

After Lee, 96, successfully lobbied President Joe Biden last year to declare Juneteenth a federal holiday, Hurst reminded her of those meetings.

“What she’s done just shows perseverance and what can happen when you truly believe in what you’re doing,” he said.

He thought about staying in Texas when he was discharged and had job offers in Dallas working with new punch-card computer systems.

But he went home to Jacksonville, he said, because “whatever I needed to fight, I would just as soon fight it in my hometown.”

In Jacksonville, he served two terms on the city council, co-hosted a public broadcasting show and continued to advocate for civil rights and Black history in a city about the same size as Fort Worth and with a similar old-guard mindset.

Hurst compared the early 1960s to today.

“As I said to my son and nephew and others when we went to the inauguration of [President] Barack Obama,” he said, “the swings during my four years in Fort Worth between great football teams, and a [Cold] war effort, and the president being killed — when you live through that, you have to be able to internalize for yourself first and then retell the story.”

He went on: “We have a lot of young people who are living through some of the most dangerous times of American history and whatever is called American democracy, and they’ve got to be able to internalize what they want and what they’re seeing.”

And tell the story in another 60 years.