This film shows how a KY radio show connects families with their incarcerated loved ones

Due to years of prison building in central Appalachia, a community radio station in southeastern Kentucky has long been within broadcast distance of 11 different federal and state prisons.

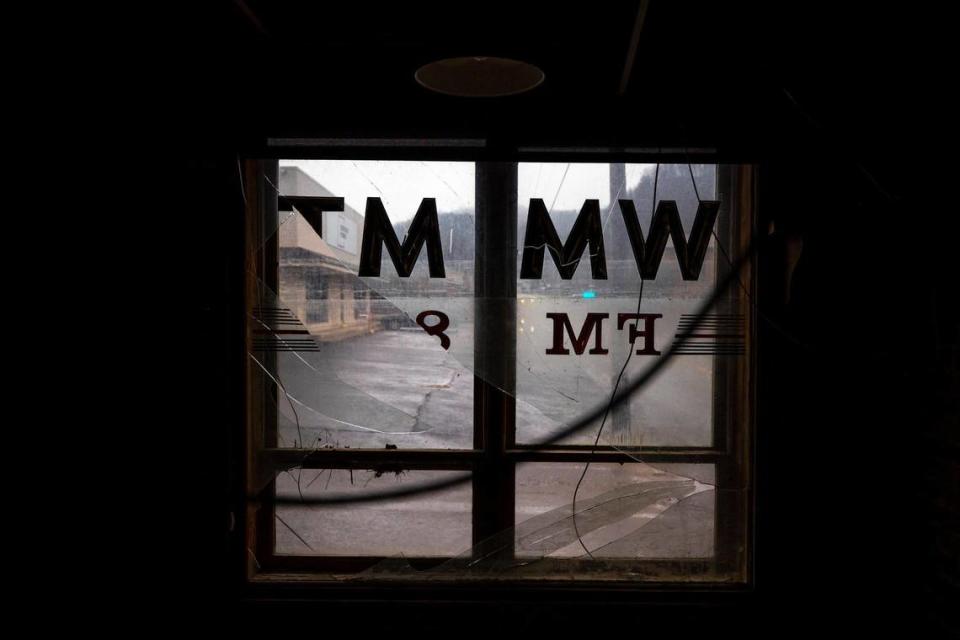

For over two decades, WMMT 88.7 has been airing some version of Calls From Home — a show specifically geared toward reaching the incarcerated with messages from loved ones. Family and friends could call into the station and record a shout-out that would be aired on the show.

“Sing a song, share a poem, or simply say hi,” reads an online description of the show on Spinitron, where those looking to listen online can find Calls From Home.

Next week, Lexingtonians will have the opportunity to see a special window into the show. An advanced cut of a documentary, also titled “Calls From Home,” will be shown at the downtown 21C Hotel at 7 p.m. March 24.

Tickets are $30. The proceeds from the screenings are meant to help WMMT’s recovery from the flood and to help keep the show’s phone lines open. Those looking to attend can register here.

Last July’s deadly flooding in Eastern Kentucky destroyed WMMT’s studio on the first floor of the Appalshop building in Whitesburg, forcing the station to temporarily move to a retrofitted trailer and knocked Calls From Home off the air for about six months. The show resumed in January.

The approximately half-hour documentary will be followed by a talkback session with a panel moderated by Shameka Parrish-Wright, the state director of VOCAL-KY. The panelists will include Judah Schept, an EKU professor in justice studies, and DeBraun Thomas, a WUKY DJ and the co-founder of Take Back Cheapside. Filmmaker Sylvia Ryerson, a former WMMT DJ, will also be on the panel.

With archives damaged, Appalshop must work quickly to restore history. There’s a way to help

The idea for the documentary came from Ryerson’s time as a DJ on the show. While she was at WMMT, outside coverage of the show picked up, she said. But much of that coverage focused on the perspective of the DJs, not on the families on the other end of the phone line or the letter writers inside prison walls.

“From hosting the show, I came to get to know people on the other end of the phone line,” Ryerson said. “And I started to think about how much that portrait of the show was leaving out and how the voices on the other end of the phone line remain unseen and invisible and unknown.”

The Calls From Home radio show has an “amazing” backstory, Ryerson told the Herald-Leader.

In 1998 and 1999, two supermax state prisons opened consecutively in Wise County, Va., just over the state border from WMMT. At the same time, Virgil Prinkleton Jr., known on air as DJ VIP, had a late night hip-hop, R&B and soul show. Prinkleton, who was from Lynch, was the only Black programmer at WMMT at that point, Ryerson said.

“(Prinkleton) first started getting letters from people inside who heard his show, and it was the only show in the area that was broadcasting music that was familiar to them,” Ryerson said. He played requested songs and started putting shout-outs on-air. After DJ VIP left WMMT, the show was formalized into a shout-out show for incarcerated people.

WMMT was Ryerson’s first job out of college, she said, becoming a radio reporter and eventually the station’s director of public affairs programming. She also was a volunteer DJ for Calls From Home. Calls come into the show from coast-to-coast and while reporting on prison expansion in Eastern Kentucky, the show allowed Ryerson to correspond directly with incarcerated people and their families.

“For me, it really made it impossible to think of these prisons as in the abstract, in the language of economic development, as they were being pushed,” Ryerson said. “It made the experience of rural prison expansion — of being separated so far from your family, being in a place that is very unfamiliar for so many people in the region — just very immediate.”

Filming for the documentary began in 2019, but funding to complete it came in 2021 from Working Films, a grassroots organization that uses documentaries to advance social justice and environmental protection.

The film also uses unique animation to show the perspective of those who are incarcerated.

“WMMT regularly receives beautifully decorated envelopes, letters, handkerchiefs sent from people who are regular listeners on the inside,” Ryerson said. “... I sought out to collaborate with artists who are currently incarcerated in facilities to work with them to figure out a way to represent their experience as a listener on the show.”

Ryerson said they commissioned a man, named Peter but who goes by Pitt, to draw a self-portrait of him listening to the radio station in his cell. They then took that self-portrait and “built movement from it.”

For the callback session after the movie, Ryerson said she’s excited to have a space to “think about how working against mass incarceration in Eastern Kentucky, you can actually work against mass incarceration in Central Kentucky.”

She’s also hoping to highlight a coalition of Eastern Kentuckians who are demanding that money possibly destined for building a medium security federal prison in Letcher County, instead go to rebuilding local infrastructure after last summer’s floods.