Filmmaker tells story of Chinese immigrants in the American South through family's eyes

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For filmmaker Baldwin Chiu, personal history makes for good cinema.

About a decade ago, eager to dive more deeply into his family’s roots, Chiu and his wife, fellow filmmaker Larissa Lam, embarked on a documentary project that began as a short film, “Finding Cleveland,” and ultimately evolved into the feature-length effort “Far East Deep South.”

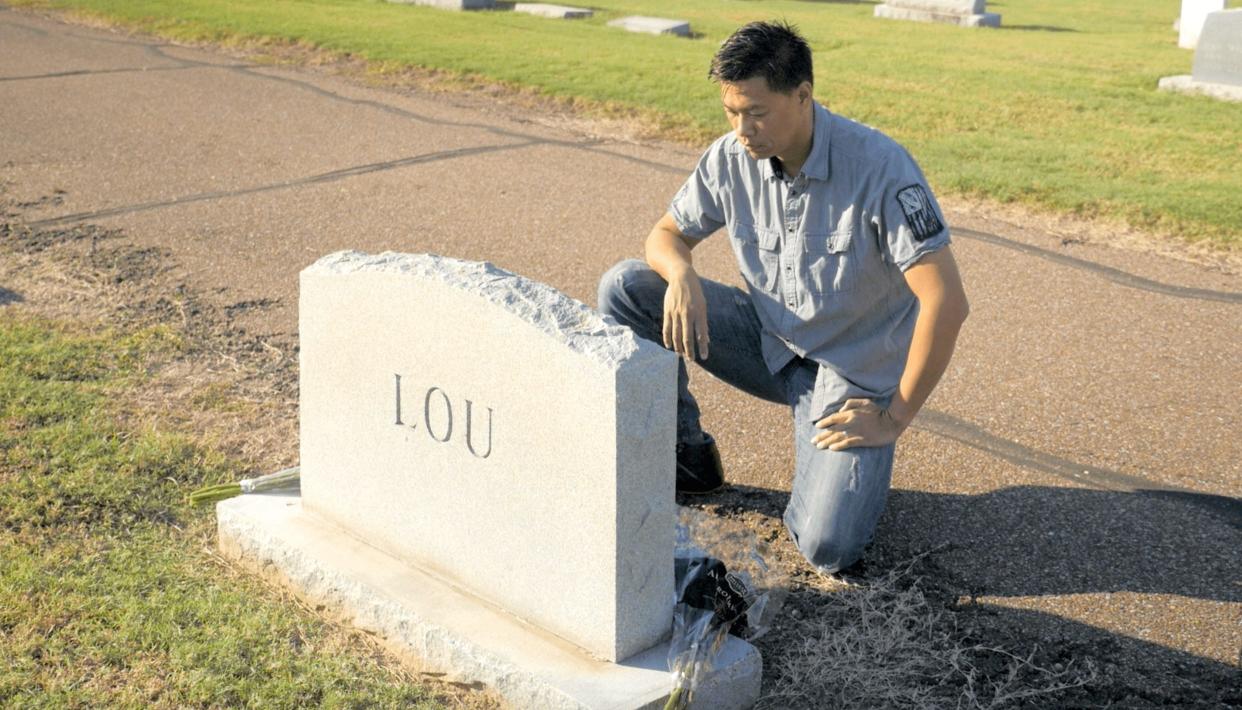

Chiu, a native of San Francisco and resident of Los Angeles, was intrigued about the backstory of his father, Charles Chiu: His father, K.C. Lou — Baldwin’s grandfather — migrated from China to Mississippi, a state that became home to numerous Chinese immigrants at the turn of the last century. There, Lou had his own grocery store.

Initially remaining in China, Charles eventually was able to move to California in the company of his grandmother — by which time his father had already died.

“Far East Deep South” — directed by Lam and co-produced by Lam and Chiu — places the family narrative in a broader political and social context.

Following numerous festival screenings and an airing on PBS’ “America ReFramed,” the film will be shown twice in Columbus on April 15: at noon at Ohio State University’s Hagerty Hall, and at 7:30 p.m. at the Hyatt Regency Columbus as part of the ASIANetwork Annual Conference. Both screenings will feature a Q&A with filmmaker Chiu and are free to attend.

The Dispatch spoke with Chiu about his family and his film.

Film: Columbus native gets big break in 'Malum' movie

Question: What story is told in the documentary?

Baldwin Chiu: The story follows the journey of my family as we discover that my grandfather, K.C. Lou, and my great-grandfather, Charlie Lou, (were) buried in Cleveland, Mississippi. Being a Chinese American family, that was fascinating to us as none of us knew this history and why they were there. This journey allowed us to not just learn more about our own family history but learn more about the history of the deep south, learn about the place where many Chinese Americans live. That was during the Chinese Exclusion (Act of 1882) era as well as going through segregation and living in the Jim Crow era as well.

Q: Why was your father (Charles Chiu) separated from his father (K.C. Lou)?

Chiu: (My father) was left behind in China. My grandfather and great-grandfather and great-grandmother were all in Mississippi. The Chinese Exclusion Act did not allow, in general, Chinese women to come to this country (without) very special application processes that made it very difficult. Most Chinese men would go back to China, start a family there, with the hopes of bringing over their sons and maybe their wives as well. Unfortunately, that process didn’t happen to go through for my father, so he was left behind in China.

Q: How did it happen that your father finally came to the U.S.?

Chiu: Unfortunately, my grandfather passed away before the passage of the bill that allowed my father to finally come over. That was part of the paperwork that was already in place, with the hopes of bringing my father to reunite with my grandfather in Mississippi.

Q: Did your father talk about this background at all?

Chiu: He actually didn’t. He rarely ever talked about it. . . . I remember wondering why I didn’t have a grandfather (and) who was my grandfather. He never told us anything, basically because he didn’t know anything. That was something we uncovered after we made the discovery of my grandfather in Mississippi, when we did more research and found more documentation and, as you’ll see in the film, meeting people who knew him.

My father started opening up about some of the memories that he remembered his grandmother sharing with him. It was one of those things where my father didn’t want to talk about it because he’d spent his whole life trying to forget the pains of growing up fatherless, the pains of coming to a new country on his own with an old grandmother who he had to also help take care of.

Asian American experiences: Two Ohioans weighed in on growing up Asian American in Appalachia

Q: What was your father’s reaction to being on camera and participating in the film?

Chiu: Initially, he did not want us to put this out in the public. We were able to have him have conversations with us and record them, and I think he thought we were just doing it for ourselves, for his grandkids. . . . Eventually, we had a discussion about how this film was no longer just about him or our family. . . . I told him, “This is an American story. America needs to know this. You are a patriot, we have been in this country for many, many generations, yet nobody knows our story.” And we constantly fight this battle of perpetual foreignness. But we’re not foreigners.

Q: How did it happen that immigrants from China came to Mississippi?

Chiu: There are several things. Unfortunately, one of the things is also a consequence of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was a nationwide act but was most felt on the West (Coast). The Chinese were helping to build the Transcontinental Railroad. They were very successful at it, and a lot of the anti-Chinese sentiments came because of the success that they had on the railroad.

So, the safest place, unfortunately, it seemed like was to move away from California and start heading east. At that same time, word was already getting out to the south about the Chinese working on the railroad and how they were very efficient and, of course, labor was very cheap. . . . At that same time, slavery was abolished. A lot of the plantation owners were finding out that they were losing a lot of their labor because of the abolishment of slavery, so where are they going to find that labor? The next best thing was to bring over Chinese off of the railroad.

The Chinese Exclusion Act also said Chinese can’t work on plantations or (in) labor jobs. The loophole was, instead of going back to China or being deported, to find a way to rent a grocery store, pool their money together (and) start a business. . . . They eventually started up these grocery stores in the Black community . . . and they were able to sell the groceries for a lower price and also accept 0% credit from the Black community. Everyone that (had been) workers benefited from each other.

Asian American milestones: 'I surely won't be the last' Asian American in Ohio Senate, says Tina Maharath after loss

Q: What do you hope audiences take from the film?

Chiu: I hope they have a better understanding of our history in America, that even though some of our history is dark, even though some of it is not pleasant, good can come out of it. If we understand those things together, then we can grow forward together.

tonguetteauthor2@aol.com

At a glance

“Far East Deep South” will be shown on April 15 at Ohio State University and the Hyatt Regency. For showtimes, registration details and other details, visit easc.osu.edu/events/easc-film-screening-far-east-deep-south-campus and easc.osu.edu/events/easc-film-screening-far-east-deep-south-campus-0.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: “Far East Deep South" to be shown at OSU and Hyatt Regency Columbus