‘Make films where black characters don’t die’: Queen & Slim sparks debate over ‘trauma porn’

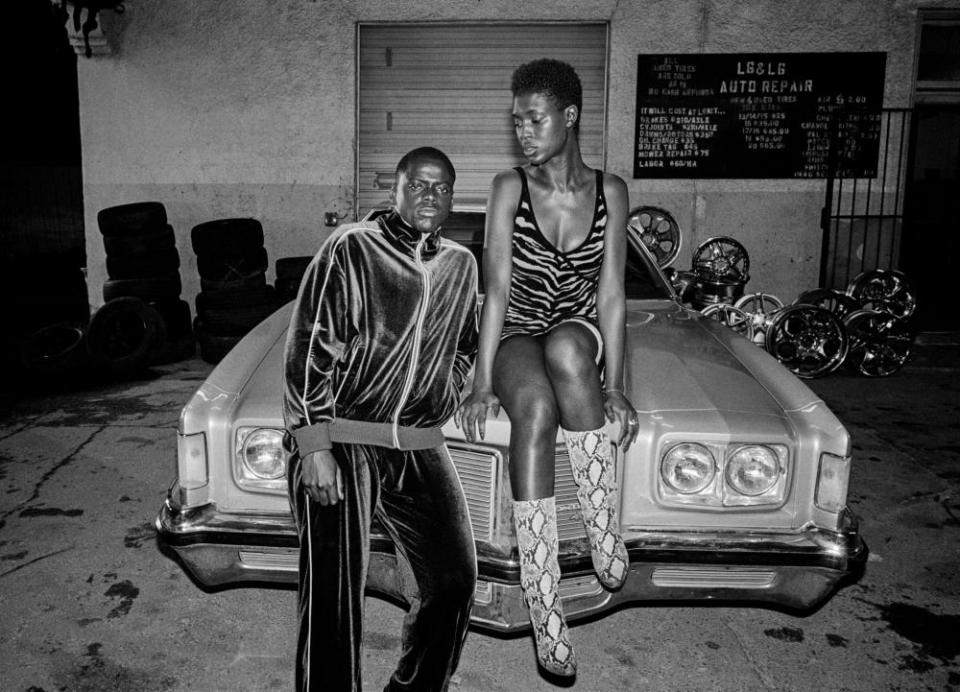

A hyper-stylized film about a black couple killing a white cop during a tense traffic stop and then embarking on a gorgeously shot escape across America was always destined to garner controversy.

Yet the debate sparked by reviewers and filmgoers about the actor and writer Lena Waithe’s debut film, Queen & Slim, is raising a series of questions about work created by black artists and the role of critics of color. Can black artists grow and become better if we don’t honestly critique them? How will more daring, inventive black films ever get funded if we tear them apart?

On the weekend of its release, filmgoers debated the pros and cons of the film. Some described Queen & Slim as two-hours of “trauma porn”, exploiting black pain and tragedy for mass consumption, while others celebrated the film’s artistic merits, praising its highly stylized cinematography and high-stakes plot.

The writer Clarkisha Kent, who covers black culture, calls the film “Black Lives Matter fan-fiction”.

Ppl should be free to critique art without the pressures of protecting ppl just bc we share the same skin color. Stop this crap now pic.twitter.com/m2hFK69rtf

— 🔥🖼Valerie Complex (@ValerieComplex) November 30, 2019

“Why is death something we have to expect in all facets of our lives?” Kent says. “We the people are more than our trauma, and we don’t have to see it over and over like it’s Groundhog’s Day to understand that it’s an issue. I feel like fiction should be an escape.”

Brooke Obie of Shadow and Act, a black-focused film blog, took issue with the film’s violent conclusion. “Black people don’t need a movie where we’re unarmed and violently gunned down by the state to tell us that we’re in danger of being framed and murdered by the police,” Obie writes. “We know.”

The film has been widely reviewed, to mixed reactions. The black women’s magazine Essence called Queen & Slim “the black love story we need”, the New York Times called it a “thrilling shock” and the Guardian described the film as “hit and miss”.

Related: Master of None's Lena Waithe: 'If you come from a poor background, TV becomes what you dream about'

In her Vulture review, Angelica Jade Bastién calls the warm-colored, Dev Hynes-soundtracked film “a beautiful object to behold but a hollow narrative to consider”.

But some of the responses to the review shocked her and encapsulated the hurdles critics of color face.

“I’m never surprised about receiving pushback as a critic,” Bastién tells the Guardian. “What surprised me was the depth of the vitriol and being called an Uncle Tom due to my Queen & Slim review, which was a very fair one.”

“Even if what you say is true, it’s wrong for you to put down another sister’s art publicly,” a user tweeted at Bastién in response to her criticism. “It’s hard enough for Black women to make [it] in Hollywood having Black saboteurs doing their dirty work.”

Bastién says the attacks are emblematic of the hurdles a black female film critic can encounter. “It can be a fraught position,” she says. “There’s a lot of weight on your words because there aren’t enough black critics at major publications and there is an expectation that you must support black art unilaterally with no regard for quality. I find this both condescending and patronizing for black art and black critics. But there’s also a tremendous lack of respect you deal with as well.”

The backlash seemed to reach a fever pitch for Clarkisha Kent.

“People are so emotional [with Queen & Slim] because of the scarcity we have to deal with when it comes to black films,” Kent explains. “It takes for ever for some of these movies to get on to screen unless you know somebody who knows somebody. So people become instantly and unequivocally protective of them – maybe even without seeing the thing.”

The drama around the film was heightened as other controversies surrounding it resurfaced.

Last weekend, the original casting call for Queen’s character re-circulated online, describing the dark-skinned character: “If she were a slave she would’ve worked on the fields.” Then there were comments made by Waithe in which she appeared to disparage black cultural influences and exalt white-adjacent ones. “I think the reason my voice is so weird and confuses people is because I study [Aaron] Sorkin, Spike Lee, Spike Jonze, and that makes me a little different than the person who only has black influences,” she said in a quote that quickly went viral.

Waithe has become an unexpected darling of Hollywood after her episode of Master of None, Thanksgiving, won an Emmy for outstanding writing for a comedy series. (Like the film, the episode was directed by Melina Matsoukas.) Waithe has gone on to produce and write a slew of buzzed-about projects, including The Chi for Showtime and Twenties, which will focus on a group of queer women, for BET.

Of course, Queen & Slim is not without its high-profile supporters. Roxane Gay, author of Bad Feminist, gave the film a glowing reviewin her profile of Matsoukas. Beyoncé, Solange and Rihanna (a trio Matsoukas has directed music videos for) attended the film’s premieres.

Kent is quick to clarify that she wants to see Queen & Slim’s director and screenwriter succeed. “Black critics don’t have it out for you,” she says, almost exasperated. “We want to help you. That’s why we say these things.”

She issues a challenge to Hollywood: “Make films where none of the black characters die.”

Despite its controversy, Queen & Slim was a success at the box office this weekend. The modestly budgeted film slightly beat box office predictions, earning $16m.

But Bastién hopes Hollywood execs glean a lesson from the intense dialogue around the film.

“I hope it shows Hollywood that it isn’t enough to merely have black people in front of and behind the camera,” Bastién says. “That the work needs to rise to the occasion. I think the pushback shows how hungry black folks are for meaningful, complex representation.” She wants work that features black characters as thriving, myriad figures.

As Daniel Kaluuya’s character says in one scene of Queen & Slim, munching on a burger and disgusted with the never-ending catch-22s of being black in America: “Why do black people always have to be excellent? Why can’t we just be us?”