The final mission

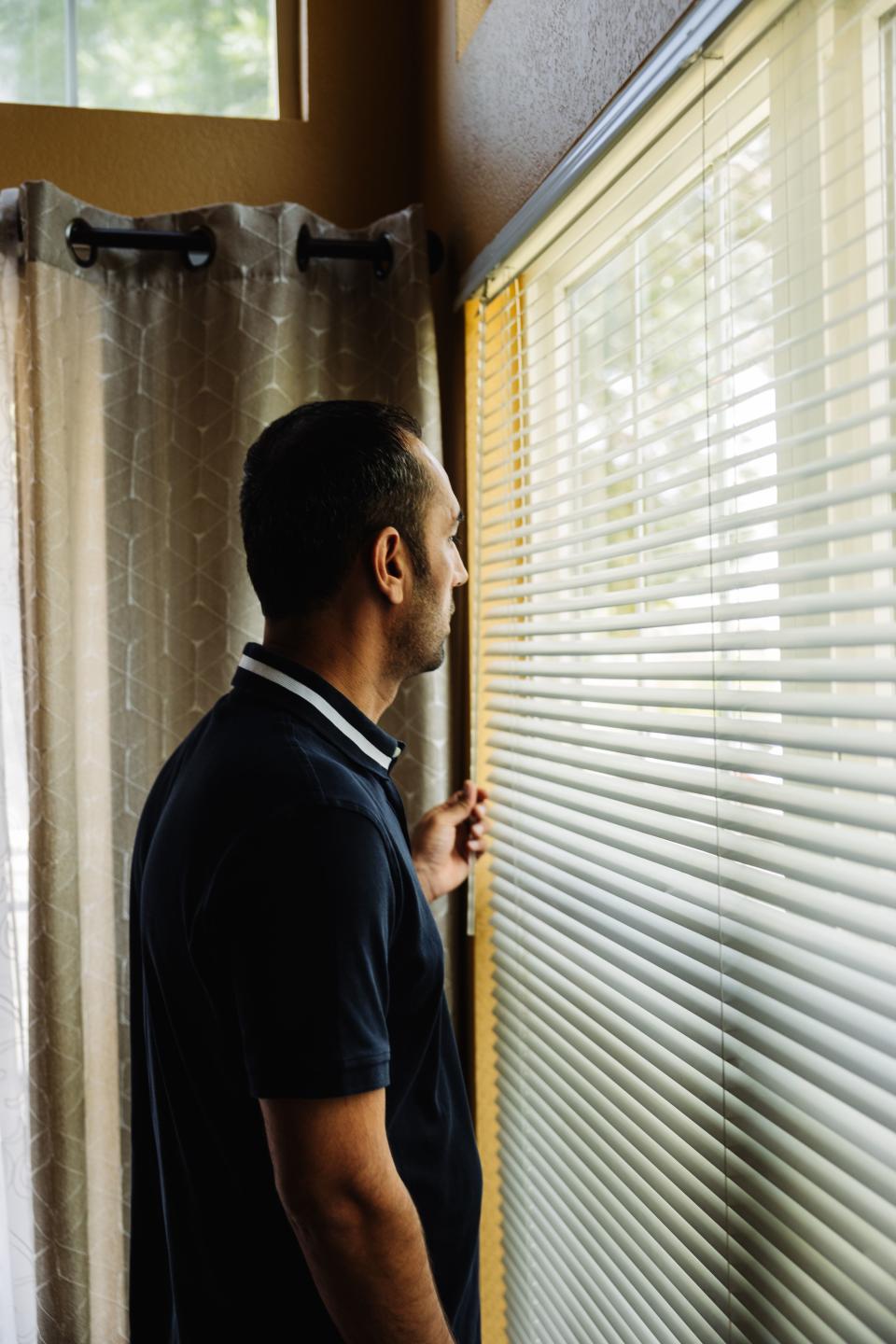

Scott Henkel tries not to fixate on the news from Afghanistan, like the story describing how the Taliban has taken Zabul, a southern province where he once built roads and schools and an almost-tactile camaraderie between the Army troops under his command and the Afghans his unit was meant to serve. The memories of 2006 and ’07 overlaid now against the reality of 2021, in the final chaotic weeks before the U.S.’s September 2021 deadline to withdraw all American military forces from Afghanistan — Henkel tells himself he’ll focus instead on his life stateside, here in suburban Denver, where he’s transitioning from one cybersecurity firm to another.

He tells himself he’ll help guide his wife and two teenage kids through the complexities of the pandemic, everybody living and working on top of each other. Life itself tries to keep him occupied, and yet the Taliban pincering the rural outposts like the one where Henkel spent good portions of his young adulthood — his work gone, undone, just poof — also shows how life does not unfold in the manner we tell it to.

Because there, on the news, other provinces, poof. The Taliban overruns a prison housing Taliban militants in Kunduz. These jailed fighters, freed from their cells, join their Talib brethren on the streets and like that they rampage on.

Like that, Kandahar falls. Kandahar! The second-largest city in the nation. Just overwhelmed Aug. 12, 2021, by the suddenly swarming Taliban.

Like that, Kabul is invaded. The capital, the last line of defense. Henkel sees it all over his Google News feed.

He puts his head in his hands. He has soldiered through life: the rail-thin high school football strong safety who surprised everyone with how hard he hit, keeping a ledger on Friday nights of the opponents he knocked out of games; the walk-on to the Colorado State track team who became a four-year letterman; the commissioned officer who, after 9/11, endured inadequate training for the nation-building civil affairs units where Army brass expected leaders like Henkel to be both fighters and diplomats. Henkel and his men had somehow still carried out 400 missions beyond the wire. Because Scott Henkel soldiered through life.

But he can’t soldier through Kabul’s fall.

He feels “complete hopelessness,” he’ll later say.

His wife Heidi sees it. Scott with his head in his hands, his shoulders drooped, his face like he’s seen a ghost, because he has: The return of the war. It haunts his cul-de-sac’d air-conditioned home, a mocking ghost. Why were you there? Why were any of you? What was the point of the last 20 years?

When Henkel talks, it’s through tears. One soldier from his tour is in Afghanistan now, less a soldier to Henkel than a brother. And as the Pentagon and State Department and Biden administration finger-point whose exit plan is to blame for the last few weeks’ disastrous collapse in Afghanistan — one hell of a way to end America’s longest war, with tens of thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands of wartime allies looking for a way out of what can only be called a failed state — Scott Henkel thinks of this brother, and this brother alone, the one whose life has for 15 years been intertwined with his.

Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi.

The one he called Kevin.

The wing man. Henkel’s eyes and ears and often his mouth, and a soldier so fiercely loyal to a free Afghanistan he’s remained there even beyond the point it’s free. That tears at Henkel. There is no Scott Henkel without Kevin, not anymore, and any story he tells of his life means a commensurate one must be told of Kevin. He’ll say this to anyone who asks. But he can only say now, through tears, what he knows of their intertwined lives: The Taliban will track Kevin down. Henkel is sure of it. The Talibs will find Kevin, Scott tells Heidi Henkel, and they’ll force Kevin’s wife and daughters into sex slavery and probably kill Kevin’s son before his eyes and then execute Kevin, too.

“Kevin’s going to die,” Scott tells Heidi.

He bawls some more.

Because what can he do from Denver to prevent it?

‘I might not live any longer’

Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi drives south through Kabul while cars, buses and people on foot flee in the opposite direction, north. Every face seems panicked. News has spread today, Aug. 15, 2021, of the Taliban’s approach on the city through its southern outposts and of President Ashraf Ghani already abandoning Kabul and fleeing the country. Khalid doesn’t doubt these reports’ veracity but has business he must resolve today near the advancing Taliban.

So he fights the deluge of traffic heading the opposite direction — cars not even obeying one-way-street signs — and glances over at his 16-year-old brother, Omar, sitting nervously in the passenger seat.

It may seem reckless for his youngest brother, a minor no less, to accompany him, but to Khalid’s mind it’s shrewd. If Khalid’s captured, the Talibs will likely spare the boy. Omar can then flee to the rest of Khalid’s family in northern Kabul and tell their parents and siblings and Khalid’s wife that Khalid has been killed.

At least that way they will know his fate.

Khalid drives his Toyota Corolla, “his low-profile car,” as he calls it, and not his Lexus. He’s also left his bodyguard back at his compound. The Lexus, the bodyguard — they would have only signaled Khalid’s high status and importance in Afghanistan.

Today they would have only put a target on his back.

He and Omar at last arrive at their point of business, the district in Kabul known as Traffic Square, its anchor the city’s department of motor vehicles. They park and get out. Terror-stricken faces, the distant boom of RPGs, smoky plumes of war on the southern horizons. It is chaos. It is also, at least for the moment, free of Talibs. Khalid motions to Omar to keep up, each of them in flowing Afghan garb to further blend into their surroundings as they approach their destination:

The travel agent’s shop.

When Kandahar fell, Khalid had given this travel agency his family’s passports in the hope that the agency could gin up visas to Uzbekistan for Khalid and his four children and wife. Khalid doesn’t know if the agency’s promise of new visas is real.

He’s here to find out.

Khalid walks into the shop. Packed, with everyone wanting the same thing: a way out of Kabul. Khalid sees his agent, an agent-liaison named Salim, and motions him over.

Where are the visas? Khalid half-shouts over the din.

Salim says he doesn’t have them. If Khalid will wait just a bit longer, Salim can deliver everything Khalid wants.

Khalid doesn’t have time. Not today. So he recalibrates his plan.

“I need my passports then,” he tells Salim. He needs some form of identification if things keep getting worse.

Salim’s not sure where those are either and disappears for a moment and, ultimately, leads Khalid to the agency’s owner, and the office in the back.

The panic in the shop, on the streets, the uncertainty of even the passports’ whereabouts — it puts Khalid on edge.

“Listen to me,” he says to the owner, a small man he doesn’t know. Khalid’s voice in its deep baritone edges into malevolence. “Don’t (expletive) with me.” He’s worried this shopkeeper has lost his passports, or sold them, or perhaps given them to some Talib as a way to curry favor.

“You better give me my passports!”

The shopkeeper, scared, opens a drawer.

The passports.

The owner hands them over and Khalid shuffles through: His three daughters’, ages nine to one; his son’s, age eight; his wife Horia’s; his own. A photo of his close-cropped hair and beard, his slight shoulders and skinny neck, next to his name:

Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi.

The man who offered 20 years of service to the Americans as a cultural adviser, interpreter and soldier. The man who tolerated some of his favorite Americans, like Capt. Scott Henkel, who could never pronounce the guttural Khalid correctly, and had settled on something easier: Kevin.

The man who has, above all, remained calm across those two decades. And so he tells himself he can remain calm today, through the collapse of his country, armed with little more than his family’s passports and his reputation.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm as he and Omar hop back in the Corolla and join the heavy sludge of traffic heading north. When the sludge becomes too thick, he exits the road and parks the Corolla at his father’s cousin Bashir’s, who agrees to take the car and hide it if only Khalid will leave. “It’s not safe for you here!” Bashir says, fully aware of Khalid’s two decades serving the Americans and United Nations and what that service means on a day like today.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm as he and Omar set out on foot, walking through a Kabul that is a bit more desperate — people looting stores — even as more people join the streets, until foot traffic is itself a heavy sludge.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm when he drops off Omar at his parents’ apartment and his mother bawls, “What will happen to you now?”

He comforts her and his wife Horia phones, terrified of what’s happening in their well-off neighborhood. Everyone is armed and paranoid, she says. Khalid tries to quiet Horia’s concern, too. He’ll be back soon, he says.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm as he walks to his luxury apartment in his high-rise neighborhood, his nose and mouth wrapped in a scarf so that only his eyes show and no Taliban scout might identify him.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm when he enters his complex, across the street from the Ministry of Interior and, moments later, unlocks the door to his penthouse apartment, his four kids rushing into his arms, crying.

When he and Horia put the children to bed, Khalid says he’ll figure out a plan for tomorrow.

Horia can’t sleep, though, and he and Horia peer from one window and then another in their five-bedroom high-rise, looking for Talibs on their street. They hear the battle: the report of high-powered rifles, the blast of artillery.

Their street itself remains still, as calm as he likes to tell himself he is.

Khalid walks through this apartment, the reward of his key insight in life, the one he learned 17 years ago interviewing terrorists for U.S. Special Forces: To not just interpret what people were telling him but provide the context of what they meant. Americans loved this broader context, this richer story. It led to a story Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi told himself. He could better his life by relaying the full story of his country. So out on missions and even in firefights alongside Army leaders like Capt. Henkel, Khalid described the narrative of why events around them unfolded. The stories he relayed from his native Dari and Pashto into an increasingly flawless English indebted him to Henkel, and other Army leaders, and ultimately to its high brass, interpreting Afghanistan for people like Gen. David Petraeus. As the years passed, Khalid went from telling the story of Afghanistan to shaping it. Working for various U.N.-affiliated organizations until, in 2018, Khalid became the CEO of a contracting firm with a budget as high as $260 million per project — and as many as 200 employees per project — that looked to rebuild Afghanistan as he and partners like the U.N. saw fit.

In this luxury apartment, Khalid has told the story of a free Afghanistan and his work crafting it to members of Parliament and the minister of justice and foreign journalists.

In this luxury apartment, though, by the following morning, the story of Khalid’s life after 20 years of shaping it begins to unspool beyond his control, beyond his authorship.

As the Pentagon, State Department and Biden administration finger-point whose exit plan is to blame for disastrous collapse in Afghanistan, Scott Henkel thinks of this brother, the one whose life has for 15 years been intertwined with his.

The Taliban are on his street with a list of names on a sheet of paper, looking for the car or apartment that belongs to Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi. Where is he, the Talibs ask? Because they’ve been following his story, too. Khalid’s son takes a video on Khalid’s phone of the Talibs searching the street, trying to find which apartment is the Siddiqis.

Khalid sends the video over WhatsApp to one of his closest contacts, Capt. Henkel. In the message beneath the video, Siddiqi will later remember typing to Henkel, “I might not live any longer.” And then, ceding that he is no longer the author of his story: “Do whatever you can do to help get me out.”

‘Let’s just try to get him out’

How to respond to that? For a while, Henkel doesn’t. He and Kevin have shared those 400 missions and then the birth of kids — messaging, phoning long after Henkel’s tour — and then the raising of families and now a mutual aging into midlife. Henkel remembers them talking often of their dream, of the Siddiqis moving to Colorado and the families living next to one another, as true friends might.

As a friend and father, then, Henkel tries to imagine the pain Kevin feels now.

“I know it’s scary,” Henkel will later recalls typing. “Try to stay strong for your family.”

What an inadequate response. That video proves Henkel’s worst fear: Kevin’s forthcoming death.

The fear slows Henkel. He sludges through his house in suburban Denver. “Completely depressed,” he’ll later say.

This depression is worse than what happened after the worst day: When a convoy that dropped him off at the airport for his mid-deployment leave in October of ’06 got blown up by an IED as it returned to its base. That explosion leveled a whole city block in Kandahar and sent three of Henkel’s soldiers to the hospital with life-threatening burns. I should have been in that Humvee, Henkel had thought at the time. I should have kept my guys safe.

The guilt he felt for the bombing in Kandahar endured for years, well after his tour. It took Heidi Henkel telling Scott, over and over, that it wasn’t his fault.

The humvees his unit drove didn’t have the necessary armor at the beginning of Henkel’s deployment. Henkel hadn’t abided that. So he’d gone above his own boss to high Army brass and demanded his team be outfitted with equipment in keeping with its ambition, its 400-plus missions beyond the wire.

Henkel got his humvees their additional, and flame-suppressant, protection before Henkel’s mid-deployment leave. And that protection saved the lives of the four people in the Humvee the IED blew up in Kandahar. “You protected them that whole time,” Heidi had said.

One of Henkel’s noncommissioned officers, Robert Benton, says Henkel had an almost “fatherly” sense of protection on tour, unique among captains.

But now that familial duty is the cause of Henkel’s depression. Because now he can’t get Kevin out. Now he can’t keep Kevin safe. As with his mid-deployment leave, now he’s not there when Kevin needs him most. The despair grows worse, and not even Heidi Henkel can reach him.

Jeff Long tries. Long was one of Henkel’s soldiers; in fact, one of the men in the humvee the day the IED blew up. Long suffered 80 percent burns on his body but all these years later he’s fully recovered and working as a cop.

He phones Henkel not long after Kevin’s first despairing messages from Kabul. They both know Kevin had applied over a decade ago for something called a Special Immigration Visa. This would give him, due to his service to the U.S. military, a new life in America. But the Trump administration’s Muslim ban and then the xenophobic fear of people with brown skin and names like Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi entering the U.S. meant Kevin’s SIV application was refused. And not once, or twice, but a third time just weeks ago.

If the U.S. government won’t formally allow Kevin to enter, Henkel says, what can veterans like Long and Henkel do?

“Let’s try,” Long says. “Let’s just try to get him out.”

Something in the way Long says it — imploring him to be the motivated team leader one last time — awakens Henkel. The war is over, the war is lost, but if they can get Kevin out, all will not be.

“I’ll do whatever I can,” Henkel says to Long.

Worse every day

There are almost too many people to kill. Under the Taliban’s new reign, the Talibs have to keep moving to find all the infidels. The Talibs with the sheet of paper asking about Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi leave to go on the hunt for other traitors, in other neighborhoods, with the promise to return later.

Peeking outside their windows, Khalid tells Horia that because the Talibs are after him, he’ll hide separately from her and the kids. He tells her to leave with the four children to her father’s home in Kabul.

He’ll be in touch.

When Khalid emerges from the apartment building, his head once more wrapped in his scarf so only the eyes show, he goes first for his uncle’s house. Khalid stays a few hours before moving onto his father’s. A routine develops. A new safe house every three to five hours.

He must keep moving. He must keep his wits about him. A colleague at the United Nations will later say more remarkable than Khalid interpreting and shaping the story of Afghanistan is the way he reveals his intelligence. “He has deep, deep, deep insights” into the human condition, the colleague says. Khalid’s life has been occupation or war. By the time of Kabul’s collapse, then, he carries an acumen about humanity most people never develop. He moves to a different safe house whenever his spidey sense — informed by chatter he hears on the street or some urge he feels within — tells him to.

This wiliness complements a separate intelligence, too. Because Khalid’s childhood was the Soviet invasion and Afghanistan’s civil wars, his grandfather helped to raise him when his parents couldn’t. Khalid’s grandfather had been a federal judge before the Soviet takeover in 1979. He had a keen mind. When the formal education system collapsed as the country did, Khalid’s grandfather impressed upon a young Khalid the imperative to read. It will free your mind and liberate your future, he told Khalid. Khalid moved through book after book, in Dari, in Pashto and eventually in English. Khalid came to love what his grandfather did: the poetry of Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet and Islamic scholar. Lines like “You were born with wings/Why prefer to crawl through life?” were not only beautiful but profound to him.

The aspiration within them led Khalid to translate for the Americans after 9/11 and, just as important, drew more Westerners to him. Be they Army captains like Scott Henkel or United Nation careerists, these people saw in Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi an ambition for life greater than his surroundings and an intelligence to rise above them.

That’s why they were as loyal to him as he was to them. That’s why, now, with Kabul descending into a nightmare, he can call his contacts from around the world. Career U.S. diplomat Jim DeHart, charged with helping to get Americans out of Afghanistan. Veterans like Scott Henkel. Europeans who know British special forces in Kabul.

The 16th of August becomes the 17th and then the 18th and every message to Khalid becomes the same.

If you and your family can get to the airport, we can help you get onto a flight.

But the airport is in the same neighborhood as Khalid’s apartment, where Talibs continue to look for him. The airport is also a series of Taliban checkpoints leading up to its gates. Stories surface of pregnant Afghan women beaten with chains or Afghan men burned alive just outside the U.S.-established perimeter of the airport, where Marines and Special Forces attempt to evacuate all Americans before the Aug. 30 deadline.

Day after sweltering day, Khalid sneaks from his hideouts and sees checkpoints and more chaos close to the airport. Thousands, tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of people begging for seats on the dozens of remaining flights out. They walk around and sometimes over the bodies of certain “traitors,” shot dead and bloating in the August sun.

One landlady backed out of leasing a home to Khalid and his family because she worried that the Taliban might blow up the residence — in suburban Denver.

In his 20 years of service, Khalid has never witnessed anything like it. He tries to remain calm for Horia, who grows ever more concerned when she calls and worries they won’t find a way out.

He tells her they will.

He carries a pistol with him though. The truth is, it’s getting worse every day. The truth is, he won’t be able to hide forever. He has to consider all options.

He settles on a contingency, one as ruthless as it is brilliant. It’s a plan he shares with no one.

If he is found, he will take his gun and unload. If there are more Talibs than there are bullets in his chamber, he will ensure his family is never discovered.

He will save the last bullet for himself.

‘He has earned his freedom’

With so little time before the Americans in the country leave Afghanistan with any wartime allies they can evacuate, every moment becomes a question Scott and Heidi Henkel must answer.

What else can we do right now?

They can phone members of Congress. They call their representative in suburban Denver, Joe Neguse. They call Congressman Jason Crow, an Afghan war vet serving a district in the Denver metropolitan area. They contact senators, diplomats, anyone and everyone at all hours of the day and always sharing the story of Kevin. How Scott Henkel armed Kevin with his own AK-47 during their tour. How often Kevin fired it. How Kevin once threw Afghan National Army soldiers fleeing a battle scene back into the flatbed of a truck alongside him, so that they all could fight as he did.

These stories emphasizing his service — and these just from Henkel’s tour — also relay Kevin’s need to get out of Afghanistan: The Henkels know that the Taliban knows these stories too. Elected officials in the States and diplomats across the world assure the Henkels that Kevin’s name has moved onto a U.S. Embassy database of people to evacuate from Kabul.

This assurance means little, though. Scott and Heidi watch the news from Kabul and the whole of the country looks like it’s fleeing. Afghans so desperate they literally break onto the tarmac at the Kabul airport and climb onto the wings of one departing plane.

“We are doing a massive disservice to our brothers,” Henkel thinks.

On Facebook, on Instagram, in group chats on WhatsApp, Afghan war vets gather to say how this evacuation is a sham. If this had been a military operation instead of a civilian one, if this had been overseen by the Army, Navy and Air Force instead of the State Department, if the U.S. had evacuated from the military base in Bagram instead of the commercial and now chaotic one in Kabul, “Everyone would get out,” Henkel says.

The evac is so broken it’s falling to the military to salvage it anyway. Scott and Heidi watch as the message boards and group chats morph into maps of the Kabul airport and logistics of how to evacuate brothers in arms — every vet has his Kevin — and rumors of what will happen once these Afghans make their approach on the airport’s gates. Scott and Heidi spend days trying to suss out who has helpful information to share, and who on the ground in Kabul can get to Kevin.

No one can.

They relay that message back. “I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die,” Kevin says in response to the Henkels. To the Henkels he talks about his anxiety of being separated from his family, his fear of endangering someone else when he moves to a different safe house, his despair of his nation falling apart and dying alongside it and never fulfilling the dream he and Scott have talked about for 15 years, of their families mingling together in America, breaking bread together in America.

Within the week of Kabul’s fall, Fox News producers contact the Henkels and ask if they would share their and Kevin’s story.

Neither Scott nor Heidi watch Fox, but they see this appearance as their last shot at Kevin’s freedom. Via satellite from a Denver television station, Scott and Heidi appear on “Fox and Friends” on Sunday morning, Aug. 22. Kevin is “somebody who I trusted with my life. … He has earned his freedom,” Scott says.

“I have a unique view, I understand also what it’s like to be a military wife,” Heidi says. “I feel heartbreak for my husband and also heartbreak for Kevin’s wife, knowing that she’s also scared for Kevin.”

“We have no time,” Scott says. “The Taliban is all over the streets. They’re going door to door … looking for Kevin. … We demand action. We must have action now from our elected officials.”

On the drive home, still in bleary shock from a national TV appearance, Scott and Heidi get an email from a former U.S. Special Forces operative.

He’s seen them on Fox. He says he has a team on the ground in Kabul.

He says he can get Kevin out of Afghanistan.

‘Go home. Grab your kids’

Hours later, a man who calls himself Hassan contacts Khalid. He does not give a last name. He says he’s aligned with a group of Special Forces who worked alongside Khalid in Afghanistan in 2004.

“Never tell anyone we contacted you,” Hassan says. “Go home. Grab your kids. Grab a backpack. Head to the airport.”

The conversation ends.

Is this legit?

Khalid messages the Henkels. Scott says to “trust” this man. The Henkels have just heard from a Special Forces operative in the States.

Khalid also knows that a former colleague at the U.N. with separate contacts within the Special Forces world has been working on his behalf.

Khalid and his contact within the U.N. next join a WhatsApp group Hassan creates, alongside three other names.

Khalid next sees a map of the Kabul airport. Hassan tells him the destination is the Abbey Gate, to the airport’s southeast, controlled by the American Marines and Special Forces.

To get to Abbey Gate, Khalid and his family must get through a Taliban checkpoint. Hassan says his contacts will meet the Siddiqi family at Abbey Gate at 8:10 p.m. By that point, Hassan will also provide to Khalid via WhatsApp the Special Immigration Visas he and his family need to board a flight. These are the same visas Khalid has requested for the last 10 years and been refused by the U.S. government. In the next few hours, Hassan says, these visas will be approved.

The whole trip, in other words, seems to be magical thinking. How will this work? He messages the Henkels how uncertain he is.

“Stay strong,” Heidi writes back. “Hug your little ones for me and tell them Aunt Heidi and Uncle Scott love them. … Hugs to you and your wife, too.”

This is, as he and Scott discuss, Khalid’s “one shot” at freedom.

He picks up his wife and family from their safe house. In their low-profile Toyota Corolla, and in traditional Afghan clothes, the Siddiqis hit the road at 5:30 p.m. The trip to the airport normally takes 10 minutes.

With tens of thousands of people crowding the streets, it takes hours.

When Khalid reaches the Taliban checkpoint, he tries, as always, to stay calm. He has hidden his family’s passports and other necessary paperwork within a secret pocket in his backpack. He doesn’t know what he’ll do if the Taliban search his phone.

A Talib motions to him to roll down his window.

“Where are you going?” the Talib asks.

Khalid’s whole life has been stories, so Khalid breathes out and relays another. “Our house is here but because of all these people” — the chaos around them — “we want to move. We want to get out of this place.”

The Talib nods: There are too many people around. Should he stop the flow of traffic to search this one family in this one Toyota Corolla?

The Talib lets them through.

Khalid exhales.

Then Hassan calls.

His unit is rescuing another family. Can Khalid head to a separate location? It would mean going back through the same Taliban checkpoint Khalid just passed.

What?!

But Khalid does it. He has no choice.

“Hey, hey. Where are you going?” the Talib at the checkpoint asks.

“I forgot something. I have to go back.”

The Talib looks suspicious, but lets the Siddiqis pass through again.

As soon as Khalid is on the other side, Hassan phones again. Now Khalid needs to go back to Abbey Gate.

“Are you trying to get me killed?!” Khalid screams.

Hassan says the new location — too many people already there. These rescues are fluid situations and it’ll be better at Abbey Gate.

By the time he has backed the car around out of the Talibs’ sight lines and reentered the flow of traffic, Khalid is convinced the Talibs will search the car. “Why me?” he thinks.

When he’s back at the checkpoint, he shows none of this despair. Just motions with his thumb that he’s good, that he’s picked up what he needs. Hundreds of cars stretch behind him and thousands of people pack the streets. A handful of guards watch everyone here, as dusk approaches.

Through the grace of Allah, Khalid passes through again. They park the car and head out on foot.

Now it’s nearly 8:10 p.m. Now those thousands of people streaming through present a new obstacle, on this side of the checkpoint. They stand in the way of Khalid and his family reaching Abbey Gate.

The line toward it is perhaps 600 meters long and packed with thousands of people.

To the west of Abbey Gate is a long fortified wall with barbed wire overhead. But to the west of this wall, down beneath it, Khalid sees a sewage canal. This sewage canal leads all the way to Abbey Gate, too.

Should he?

He tells Horia to wait here with the kids.

He jumps in the sewage canal. The sludge comes up to his chest and the smell gags him. He keeps his phone in his hand high above him and starts moving through the river of excrement.

Some of the Afghans seem amazed at Khalid’s desperation. Some see him as clever.

A few others jump in.

Khalid focuses only on the Marines in the distance.

It’s tough going. Uneven surfaces underneath. He slips and nearly falls many times. He’s also exhausted. He hasn’t slept since August 15th.

Bring them all here, Scott Henkel and thousands of vets like him say, through a bill now before Congress, the Afghan Adjustment Act, which seeks to evacuate the 200,000 remaining wartime interpreters and soldiers.

But he wades on, through urine and feces and trash.

It’s nearly dark when he reaches the Marines.

“Where are you going?” one barks.

“I work for you guys!” Khalid shouts back.

The Marine doesn’t believe it.

Khalid phones Hassan, and ultimately Khalid hands the Marine his phone so the Marine may speak with Hassan directly. This Marine then retrieves his commanding officer inside.

Go back and get your family, the Marines say.

Khalid does. He wades back through the river of poop. He puts his oldest daughter on his shoulder and then heads back toward the Marines. They take her and Khalid walks back through the feces for the next child.

On and on until it’s pitch black and he at last holds out his hand so Horia can step down into the sewage. She does, wrapping her arms around his shoulders. Together they wade to the Marines.

When they reach them and the Marines hoist the couple up, Khalid asks for his phone.

His first message is to Scott Henkel.

“Sir, I’m across,” he types.

‘Bring them here’

It’s mid-morning in Denver and Scott Henkel has returned from a trip to the grocery store when he sees the message from Kevin.

A knot of tension dissolves in his chest. He has to sit down in a chair.

His son Connor unpacks groceries and looks over. “Dad, are you OK?

“Buddy,” Scott says, “I’m better than I’ve been in a long time.”

They would have that big shared meal. The Siddiqis would even settle in a home minutes from the Henkels, with no rent for a year, thanks in part to Heidi’s fundraising efforts in the greater Denver area.

But to tell a story rooted in Afghanistan is to expect no bow-tied Hollywood ending. First off, there are too many other stories, too many other Kevins. Over 200,000 wartime allies have been left behind in Afghanistan. Left for slaughter, for something like genocide. “My friends shot dead,” Khalid says in a recent interview, his eyes welling with tears.

Survivor’s guilt is as real as America’s ongoing fear of Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi. One landlady backed out of leasing a home to him and his family because she worried that the Taliban might blow up the residence — in suburban Denver. She’s not the only ignorant American. Despite the professional headshot the Henkels arranged and a resume which shows Khalid working as the CEO of contracting firms aligned with the U.N. or Afghan military, overseeing a staff of 200 and with some project-based budgets over $200 million alone, Khalid can find only menial work here. Jobs well beneath his expertise. For the whole of his adult life, he shaped his story and now, “I feel like I got stuck in a situation,” Khalid says. “I’m this close to maybe going back to Kabul.”

“There’s no Afghanistan to go back to,” Scott says in a recent interview. “And I’ve told him that multiple times.”

Through red eyes, Scott sees his friend suffer and weigh a return to a place that only exists in Khalid’s mind. In some sense, Khalid is still walking through that sewage canal. Undignified work, culture shock for his and Horia’s children, the memories of 20 years of war on a loop in his head.

What do we owe Khalid?

Scott Henkel has posed this question a lot over the last two years. We owe him “empathy,” Henkel says. After the collapse of Kabul, the relief of America, sure, but “starting from absolute zero. No Social Security card. No credit. No money.”

We owe Khalid and people like him more than that, too, he argues. They stood beside Scott and other U.S. troops when American leaders wouldn’t. Distracted by a second front in Iraq, uncertain what winning in Afghanistan even looked like — the irresponsibility of that, the thoughtlessness, it grates on Henkel. Two decades and trillions of dollars and millions of affected lives and now one endless question.

For what?

Scott Henkel thinks he has an answer. “Bring them here,” he says.

The wartime allies who remain in Afghanistan, and still hide from the Taliban — evacuate them as we evacuated our Vietnamese allies after Saigon fell. Bring them here and help them as we did those boat people in the ’70s, and watch as Afghans thrive as Vietnamese have. Bring them all here, Scott Henkel and thousands of vets like him say, through a bill now before Congress, the Afghan Adjustment Act, which seeks to evacuate to the U.S. the 200,000 remaining wartime interpreters and soldiers and their families.

Because that is what we owe them: The respect they gave us. The trust they gave us.

“Bring them here,” Scott Henkel says, and watch, after two decades of war, as a peaceful and shared story unspools.

This story appears in the October issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.