What’s So Bad About Fixing Oil Prices?

The Federal Trade Commission accused former Pioneer Natural Resources Chief Executive Scott Sheffield earlier this month of colluding with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. That sounds sinister, but is it?

Antitrust laws prohibit collusion, and mostly for good reason. It leads to a lack of competition, causing higher prices that harm consumers. The only winners are the companies involved that get to maximize their own profits at the expense of consumers. In more-recent decades, industries accused of collusion have included airlines and credit cards. Yet oil is a commodity for which that neat equation—more competition, less harm—is frequently complicated.

Most Read from The Wall Street Journal

Stubbornly High Rents Prevent Fed From Finishing Inflation Fight

Wealth Managers, Charities Defend Fees From Donor-Advised Funds

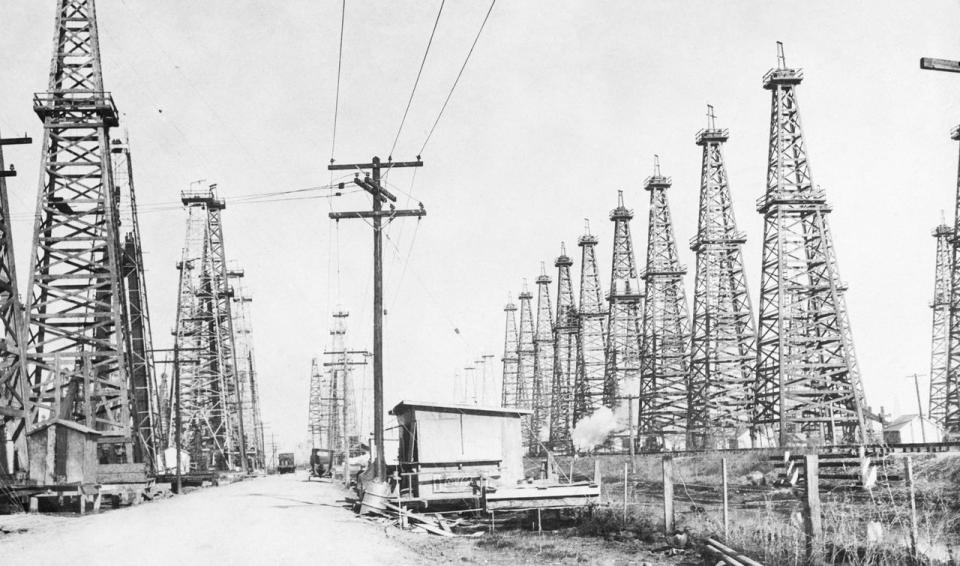

Oil’s history is full of attempts at stabilizing prices. Petroleum is an essential commodity that has high capital needs and long lead times: That lends itself to boom-and-bust cycles that are painful for consumers, governments and companies. There is no immediate cure for price spikes or plunges because it is impossible to turn on significant new oil supply or to turn off demand for it on short notice. Storage helps, but oil must be kept underground or in specialized tanks.

When done effectively, managing oil supply tames volatility. The wild boom-and-bust cycle between 1859 and 1879, for example, was followed by a period of relative price stability, when John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil monopoly reigned.

In fact, the most stable period of oil prices was between the 1930s and 1970s when the Railroad Commission of Texas tightly controlled supply, according to analysis from consulting firm Rapidan Energy Group. At the time, Texas set the rate at which every well in the state could produce, using the military to monitor compliance and coordinating with other states. OPEC is the most recent example of supply management, though it has been less effective.

Legal considerations aside, passing judgment on price fixing ultimately comes down to whether one believes oil-price volatility causes more harm in the longer term than good.

Proponents of oil supply management say that the boom-and-bust cycles are too painful. Rapidan founder Bob McNally says the only thing worse than oil supply management is the lack of oil supply management. Price swings can complicate monetary policy, make national budget planning difficult and even trigger social unrest in oil-dependent countries, he argues in the book “Crude Volatility.”

Energy economist Anas Alhajji said in his newsletter that high oil-price volatility leads to a “waste of resources, higher costs, and a deterioration of efficiencies in oil production and consumption.”

But stable prices also mute market signals. High oil prices in the 1970s following the Arab oil embargo and Iranian Revolution encouraged the development of high-cost oil resources such as those in Alaska, the North Sea, Mexico and Canada, ultimately helping the world become less reliant on OPEC for oil.

And high prices in the 2010s helped U.S. producers pursue fracking aggressively. The bust that followed pushed frackers to find efficiencies. Proponents of supply management, though, say stable prices are more conducive to long-term investment than up-and-down cycles. Looking forward, price signals are also an important nudge for alternative energy sources, says Arjun Murti, partner at energy research and investment firm Veriten.

There are a few reasons price fixing seems less necessary today. First, for all the alarm bells that go off when pump prices rise, volatility hurts a lot less—at least for some countries. The U.S. went from importing twice as much oil as it produced in 2006 to becoming a net exporter starting in 2020. And fuel now takes up a smaller portion of Americans’ budgets: Households on average also are wealthier than they used to be and cars are more fuel efficient.

Second, fracking itself has helped supply respond faster because shale wells using the method can be brought online in a matter of months rather than years. U.S. shale has helped reduce global oil-price volatility, according to a working paper by economists at the Dallas Fed. And there is at least some evidence that demand itself has become slightly more responsive to high fuel prices—possibly because more people have the option to work from home. This applies to only a fraction of the world’s population, though.

Associating “OPEC” and “collusion” with an American energy CEO sounds bad, but it is also hard to see how effective Sheffield could have been. Oil production is so scattered: There are thousands of producers in the U.S. alone. And OPEC itself, which comprises many countries with diverging goals, has failed many times to collude.

Moreover, some of the few successful initiatives have come from consumers. In 2020, it was then-President Donald Trump himself, a champion of free markets, who helped broker an OPEC+ deal when prices had plunged.

Thankfully for consumers, price-fixing isn’t only less necessary today but also a lot harder to do.

Write to Jinjoo Lee at jinjoo.lee@wsj.com