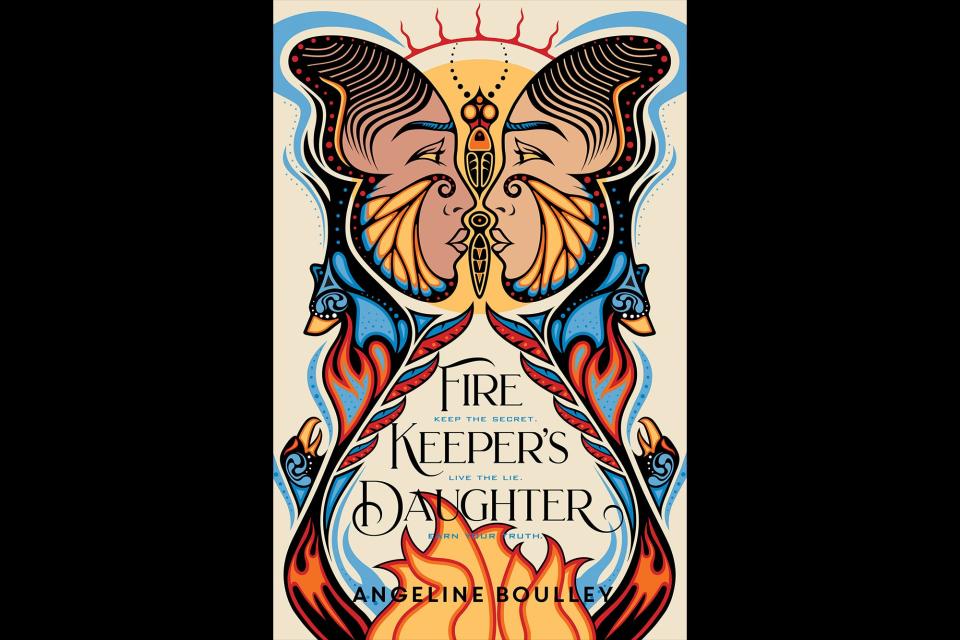

'The Firekeeper's Daughter' reminds how traditions can tackle challenges

During my many years of teaching, I was typically the one giving out required reading assignments. Now, as part of a class I’m helping to teach this summer, I’m on the receiving end of such an assignment.

I admit I should have long ago read “The Firekeeper’s Daughter,” but had not. Until now. You should read it too, if like me, you’ve been slow on the uptake.

Angeline Boulley’s young adult novel is set in and around Sault Ste. Marie and nearby Sugar Island, where eighteen year old Daunis Fontaine’s family is as much a part of the landscape “as its spring-fed streams and sugar maple trees.”

But these ancestral roots are not enough to protect Daunis, as her family’s complicated connections are either critical or contemptible, depending on who is explaining. In what she calls “the new normal,” Daunis spends her mornings running the roads and paths of the Soo, before visiting her grandmother Mary Fontaine, recovering from a stroke suffered in her grief after the death of her son, Daunis’s uncle David, a local high school teacher.

This is only a fraction of what Daunis navigates, however, as her native neighbors, and the wider Upper Peninsula community battle the demons of the methamphetamine plague. Turns out this scourge might be closer to Daunis than she could have ever imagined, even.

Narrated in the first person, Boulley’s Daunis is fierce, frightened, and focused on not only helping find out who’s supplying the meth, but also on discovering how she can walk the invisible but powerfully elemental line marked by the native blood of her father’s family, the Firekeepers, and her mother’s influential roots as a Fontaine. Also navigating near this line is her brother Levi, a hockey player and all around big man on campus, and hopefully one of her most likely allies.

There is plenty for Daunis to worry about from the beginning and then Boulley turns the screws even tighter when drug-diminished Travis Flint kills her best friend Lily Chippeway and Levi’s new hockey teammate Jamie Johnson turns out to be an undercover cop trying to discover the source of the meth. Daunis is in deep but can get out only by going in deeper.

Boulley doles out details with a deft balance as we discover the bottom is so much lower than first imagined. After Lily’s murder, Daunis wants to wake up from her nightmare, and is willing to “reveal every secret to Jamie that I’ve been keeping. The truth about Uncle David’s death. Why I don’t play hockey anymore. What my mother did after she found Dad in bed with Dana (Levi’s mother) at a party on Sugar Island the night she planned to tell him about me. How Guy lies started.”

Before she can do any of this, however, she must first determine how much to trust Jamie, and whether she can rely on what she knew of her uncle as well as where her brother’s allegiances fall. Her certainties are challenged even as her family’s story, Firekeepers and Fontaines alike, collide in ways she can neither predict nor prepare for.

Throughout, via Daunis and the wider Ojibway community, Boulley poignantly portrays the pathos of teens caught in a world where trouble is as common as calm, as well as a collective ethos challenged when old troubles are inflated with new circumstances.

The book’s success, and certainly at least one reason for its warm reception, as well as a reason for our summer reading assignment, is Daunis’s recognition of both her obligation and her opportunity as “The Firekeeper’s Daughter.”

Good reading.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: 'The Firekeeper's Daughter' reminds how traditions can tackle challenges