The First Blockbuster Testimony of the SBF Trial

This is part of Slate’s daily coverage of the intricacies and intrigues of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial, from the consequential to the absurd. Sign up for the Slatest to get our latest updates on the trial and the state of the tech industry—and the rest of the day’s top stories—and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

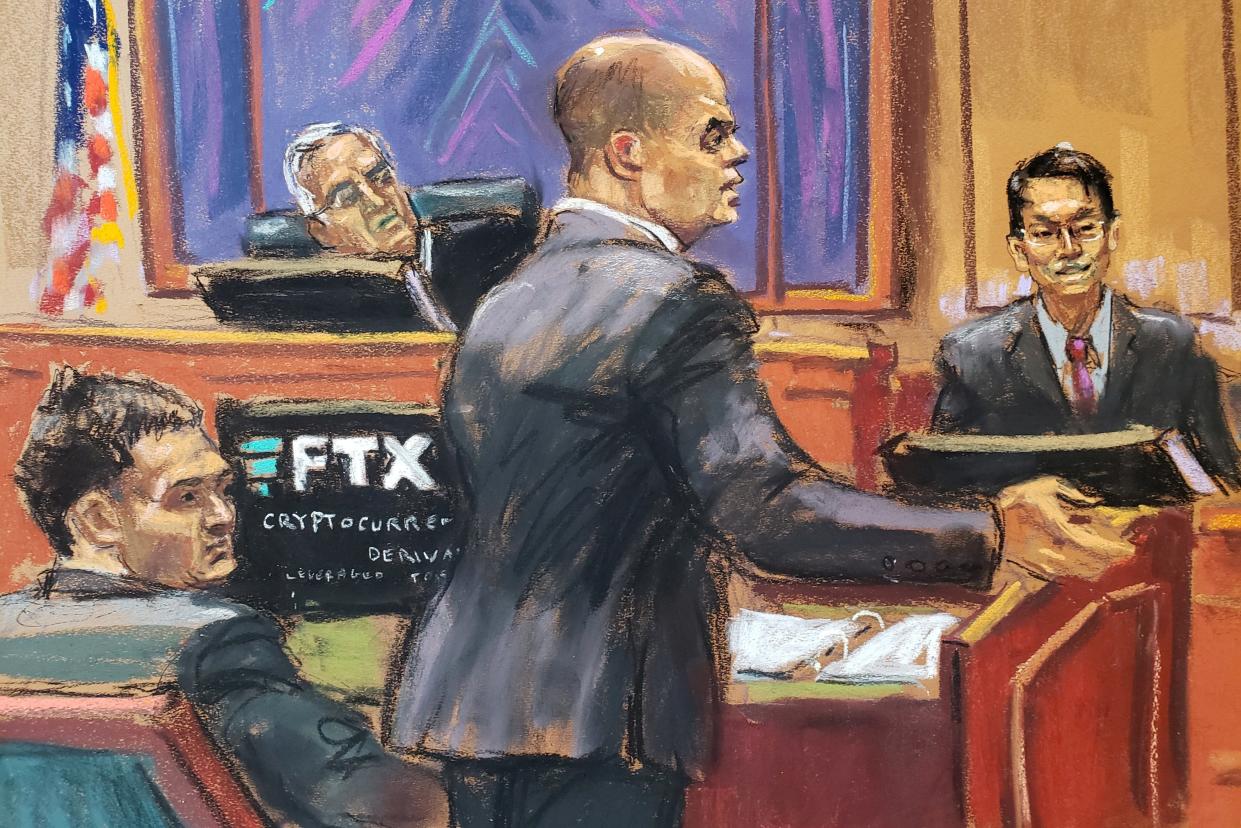

The first week of United States v. Samuel Bankman-Fried concluded Friday afternoon following a marathon of detailed testimony from an especially key SBF confidant: Gary Wang, the former FTX engineering director who’d first taken the stand Thursday evening (and who’ll return Tuesday to finish cross-examination before yet another highly anticipated witness, Caroline Ellison, says her piece). This was the trial’s most granular session yet, with the prosecution utilizing financial spreadsheets, lines of code, lots of cryptocurrency jargon, verbose tweets, and an “excerpt” of a dang Matt Levine podcast with SBF—not even that infamous “Ponzi business” segment!

What did it all amount to? The prosecution showing, again and again and again, how SBF’s private activity contradicted everything about his public do-gooder image—and how, according to Wang, SBF used FTX’s sister hedge fund, Alameda Research, to siphon customer funds to use for various unapproved purposes. The day’s presentation was dense, the fruits of some impressive financial forensics work. It’s Friday, and you’re reading about a white-collar fraud trial by choice, so I trust you’ll permit me a couple thousand words.

First up on the exhibit screens: screenshots from the FTX database, displaying how the site’s backend logged transactions from particular users. Prosecutors showed the court an important piece of code: “allow_negative,” indicating which FTX clients were allowed to withdraw more money from the exchange than whatever was left in their account, thereby recording a negative balance. Why did FTX code such a feature? Well! It turns out the one FTX customer allowed to go negative was … wait for it … a li’l crypto hedge fund known as Alameda Research, co-founded by Wang and SBF in 2017.

As Wang explained, shifting in his seat and gesturing with his hands throughout, Alameda earned an “allow_negative” badge because it helped the firm sidestep the automatic procedures Wang implemented to prevent account overdraws and wipeouts. The bespectacled Wang made clear that Alameda was indeed treated “differently” than FTX clients—granted large lines of credit that were allowed to balloon over time (from $1 million to $1 billion to … $65 billion) sans any real-world collateral; given the ability to process its own requests faster than others’; and allowed to withdraw billions from FTX, though its own account had never debited such billions to begin with. Aside from Alameda, Wang clarified, only a few major FTX customers ever held credit lines and collateral in excess of $1 million, forget a whole billi.

And where did those funds to Alameda come from? From other FTX customers, Wang said, all of it eventually amounting to an $8 billion liability to the exchange by the time FTX collapsed in late 2022. (But hey, SBF’s lawyers later argued, it never surpassed the $65 billion credit line, now, did it??)

It was in July 2019, just a few months after FTX’s launch, that Bankman-Fried instructed Wang and chief technology officer Nishad Singh to construct a backdoor on the exchange for Alameda. As Wang testified, SBF wanted the exchange to act as backstop for expenses related to FTX’s in-house token, FTT. You may recall what FTT was if you followed the FTX collapse as it went down. Wang described the FTX-exclusive currency as a “sort of equity” in the exchange—i.e., a price-linked indicator of the business’s confidence and health, and a form of collateral for the customer deposits contained within. But how Alameda used the backdoor was to take out tons of customer money and throw it toward investments in companies SBF was enthusiastic about, Wang said. Every time Alameda’s FTX account went negative, it meant the hedge fund had not only cut into FTX’s revenue from trading fees, but was also employing customer deposits for untoward purposes, Wang said. As displayed in yet another coding exhibit, Singh had personally made changes to the FTX database on July 31, 2019, adding two column categories—“allow_negative” and “can_trade_futures”—for customers with those advantages. It turns out, Wang said, that Alameda was then sorted into “allow_negative” on the very same day. (As the prosecution later entered onto the record, SBF had tweeted on that same July 31 that Alameda’s “account is just like everyone else’s” on FTX. That was untrue, Wang admitted.)

Alameda is a liquidity provider on FTX but their account is just like everyone else's. Alameda's incentive is just for FTX to do as well as possible; by far the dominant factor is helping to make the trading experience as good as possible.

— SBF (@SBF_FTX) July 31, 2019

A subsequent exhibit, consisting of a GitHub screenshot from Aug. 1, 2019, further emphasized the point. Singh wrote there that “we set allow_negative=true for” myriad accounts belonging to Alameda Research, which remained the only FTX client set that way—a status it held until the very end. No, SBF did not code this himself, nor did he actually look at the change, Wang said. But he did order that it be done, and his loyal lieutenants made it so.

March 2, 2020: another codebase shift for FTX, this one involving the addition of an “insurance fund” page to the website. Some lines of code highlighted by the prosecution deconstructed how this insurance fund—meant to serve as reassuring backup to users whose accounts’ worth might fall due to currency-value crashes—was also misrepresented to the public. The insurance was configured by taking FTX’s total trading volume from the past 24 hours, multiplying that by some random number (no joke, Wang denoted this variable as “a random number that’s around 7,500”), and dividing that by 1 billion. This gave the public page a bigger insurance-fund figure than what was actually available in FTX’s coffers, which was determined by account liquidations. We’ll get back to this in a bit.

Jump forward to May 22, 2020. The government put up a separate GitHub screenshot from that date, this one centering a comment from Wang. The code was from the “liquidation engine” at FTX—that is, the tool built into the exchange to serve as automatic barrier should a certain cryptocurrency go down in value and tank a customer’s non-fiat FTX holdings. The purpose was to make sure no users got zeroed out in this circumstance, with FTX kicking in collateral as needed. You know what accounts weren’t subject to the liquidation engine, though, per Wang’s 2020 code? I knew you’d get it: Alameda’s, because SBF & Co. needed those balances to dip below zero if they were to transfer customer funds out of FTX and to the hedge fund, Wang said. SBF was not only aware of this, but he had insisted to Wang that Alameda accounts “never” be liquidated.

OK, onward to Valentine’s Day 2021, and back to the aforementioned insurance fund. This here tweet from the official FTX Twitter was written, Wang noted, by SBF himself—and it was another lie, because “there was no FTT in the insurance fund,” Wang continued.

The 5.25 million FTT we put in our insurance fund in 2019 now makes the fund worth over 100 million USDhttps://t.co/tMYgJOAdqI pic.twitter.com/vQDkmkufD2

— FTX (@FTX_Official) February 14, 2021

Guess which entity actually owned copious amounts of FTT and served as the real backstop to the insurance fund? Say it with me, folks: Alameda! To inflate the insurance fund for FTX customers and pretend to be secure, Alameda’s account took on losses realized in the auto-liquidation of value-shedding FTX accounts. And who requested that this be done? You already know: “SBF asked me to go into the FTX Database … so that Alameda took the losses instead of the insurance fund,” said Wang. (Something important to mention here: Alameda Research was not required to be as financially transparent as FTX, which had to present consistent records to outside investors. And SBF was quite conscious of this, Wang pointed out.)

This head-spinning cash-flinging saga segued into an Odd Lots episode from spring 2021, 35 seconds of which was played to the court in rather loud, distorted audio. (Helpfully, the jury had printed transcripts.) It was the same notorious podcast in which SBF all but agreed with Matt Levine’s characterization of an FTX offering called “yield farming” as a Ponzi scheme. What the court heard was Levine’s query to Bankman-Fried regarding FTX’s “risk management”: “Do you guys regularly have blowouts where you’re not made whole?” SBF had replied, “We’ve never had a day, I think, where there’s more money that we’ve lost in blowouts to revenue that we made just from trading fees.” That was also a lie, Wang told us—the revenue-overwhelming losses were just shuffled over to Alameda, nothing to see here.

Bankman-Fried slouched back in his seat, arms splayed out limply at his desk, while Wang persisted through the timeline of how Alameda drew up FTX deficits that were, uh, larger than the sum of FTX deposits altogether. Wang discovered in 2021 that Alameda had recorded a $200 million deficit with FTX, even though the exchange retained a total circulation of $150 million. “I was surprised,” Wang said; he brought up his concerns to Bankman-Fried, who then asked him whether he’d accounted for FTT balances while calculating the gulf. The thing is, Wang explained, they couldn’t publicly disclose an accounting that incorporated the value of FTT—which was only worth a few dollars at the time, and which was mostly held within Alameda—because the value of FTT would actually drop if it was revealed to the public that this in-house coin was covering for Alameda’s FTX withdrawals. (And those withdrawals had been subsequently splurged elsewhere by SBF and friends, including in risky venture investments.)

Still, “I trusted [Bankman-Fried’s] judgment,” Wang said, deciding not to press further and rock the boat. And he continued to boost Alameda’s credit line (gradually, toward that $65 billion) with SBF’s approval, whenever Alameda was about to take out too much in FTX deposits. Number too big? Just make number go up.

Crisis mode did hit, finally, in June 2022, when the crypto world was in the thick of a severe downturn. In a group chat, SBF asked about Alameda’s exposure to FTX, as part of his preparation for an influx of customer withdrawals. Now, remember the year-old tracking bug Adam Yedidia had pointed out in his testimony earlier this week? It had grown to the point where Alameda’s FTX account measured at negative $20 billion. But even when the bug was patched, Wang had calculated (as shown in a spreadsheet containing the useful label “Gary’s number”) that Alameda still owed $11 billion to FTX. And, well, this was a greater amount than what FTX had for itself.

Alameda was in quite the hole! Which perhaps inspired SBF to discuss the possibility of dissolving the hedge fund altogether, in addition to an impending Bloomberg article that would expose the close ties between Alameda and FTX. Bankman-Fried suggested (without telling Ellison) that he, Singh, and Wang find another firm to replicate Alameda’s role with FTX. Conveniently, he had in mind a fund called Modula, which 1) SBF held a major stake in; and 2) was led by two former Jane Street traders, one of whom SBF had dated (and was not his ex-girlfriend Ellison). Yet to dissolve Alameda, they’d need to scrounge up $14 billion to cover Alameda’s liabilities, and they didn’t quite have that money. Not even from FTX customers.

We now make our way to those fateful November 2022 weeks during which Wang and SBF had their ultimate split. The FTX CEO took over his company’s social media to tweet on Nov. 7 that a large amount of Bitcoin withdrawals was causing a slowdown in FTX’s processing. That was a lie, said Wang, because the delay came from the fact that FTX hadn’t enough stablecoins (or enough of any form of money). Hours later, without consulting Wang, SBF sent out the notorious tweet where he declared, on his personal account, that “FTX is fine. Assets are fine.” Wang’s take on it to the court? “FTX was not fine, and assets were not fine.” That whole thread was full of lies, claimed Wang: FTX did not have enough to “cover all client holdings,” because that money was lost in Alameda’s taking-and-investing. SBF saying FTX didn’t “invest client assets” was also false, because Alameda money went to various SBF investments.

The real betrayal came right after the FTX-Alameda bankruptcy, around Nov. 12, when SBF ordered Wang to transfer FTX’s money to Bahamian securities officials—because they “seemed friendly” and would allow SBF to preserve some stakes in his businesses. (Even though the money that propped up those businesses … really belonged to customers.) Another Signal chat presented to the jury showed Ryne Miller, the counsel for FTX.US (the U.S.-facing part of the exchange) demanding that FTX stop transferring money to the Bahamas government, because many of the assets fell under U.S. jurisdiction. Ignore that, said SBF to Wang; keep on sending it to the nice island folks. A few days after that, Wang returned to the U.S. and met with government investigators. He wasn’t arrested or charged, but he did wish to cooperate, and thus pleaded guilty to eventual charges of wire fraud, securities fraud, commodities fraud, and more. And here we are.

After all this? The defense didn’t seem to get too much of anything new out of Wang, once again inviting Judge Kaplan’s opprobrium with its line of questioning. It’ll probably be the same thing next week, when Wang finishes his cross-examination. And then another star witness: Caroline Ellison. Catch the excitement!