First fire, then flood: Inside Caltrans’ effort to repair washed out Highway 1 in Big Sur

In Big Sur, mother nature is hard at work healing from the Dolan Fire.

In many places, it’s a peaceful transition. Fresh, green growth covers fire-blackened hillsides, hiding the remains of the massive blaze that scorched the region and shut down one of the world’s most scenic routes last summer.

But in other areas — such as Rat Creek, just north of the community of Lucia — the burn scar fought back.

There, a dangerous mixture of water, mud and debris swept two lanes of Highway 1 into the Pacific Ocean during a late January storm.

On a recent visit to the site, all that remained of the road at Rat Creek was a massive, gaping hole, still bleeding mud and rocks down into the ocean below.

Now Caltrans has its own healing mission: Remove the remains of the washout that sliced across one of the state’s most beloved roadways and get the vital highway open as soon as is safe.

After all, a potentially greater force than mother nature is also at play: economics.

“The state highway system is here to enhance the economy,” Caltrans District 5 spokesman Jim Shivers told The Tribune during a Rat Creek site visit Thursday. “When this highway is reopened, then we’ve done our part in enhancing the economy and allowing California to have a transportation system that works for them.”

It could be a long road though.

Big Sur has a history of mudslides, road closures

Mudslides and weather-related road complications aren’t uncommon in Big Sur.

Any old-timer can recount numerous slide events throughout the region. There was the slide in 1983 that shut down Highway 1 for 13 months. Then in 1998, a drainage pipe whirlpool formed along the road near Gorda, and once again the road went tumbling down.

One of the largest slides in recent memory was the Mud Creek Slide, which in 2017 sent 6 million cubic yards of mud and debris rolling down the hillside, completely burying Highway 1 in what was described at the time as “the mother of all landslides.”

That massive event shuttered the highway for a year-and-a-half.

“As I tell people, even under the driest conditions out here, we are at the edge of the continent,” Shivers said. “The geography, the terrain, is always under some state of movement. Introduce a lot of water to that and you have the potential for mud and rock slides in any number of locations.”

During the January storm, Shivers said, Caltrans responded to close to 60 separate weather-related road events through the Big Sur corridor.

Photos from Jan. 29, compiled by the United States Geological Survey as part of its effort to map and track changes to California’s coast, show great swaths of the coastal highway covered in mud and debris immediately after the storm.

These photos show a film of brown for miles along the Pacific Ocean’s edge, marking where debris made its way down to the sea.

But those areas didn’t see quite the fallout that Highway 1 at Rat Creek did, so what specifically went wrong that caused the road failure?

Essentially, it was a victim of fire, water and physics.

How Dolan Fire impacted Rat Creek slide

On Aug. 18, 2020, a fire broke out near Dolan Ridge at the edge of John Little State National Reserve. Its origin is still unclear, though criminal proceedings are underway for a Fresno man accused of intentionally setting the blaze and throwing rocks at firefighters.

The Dolan Fire lit up the dry region like a tinderbox, making a mad, explosive dash across federal and state lands and endangering hundreds of homes throughout the region.

The wildfire, which wasn’t contained until Dec. 31, 2020, left a massive scar. It charred 124,924 acres, destroying trees and brush and taking the lives of at least nine endangered California condors.

Right at the edge of all that is Rat Creek.

The unusually named creek sits just south of the area where the Dolan Fire broke out.

Rat Creek runs almost straight up a mountain about two miles, before ending at 3,010 feet above sea level. Water from the creek feeds into a drainage culvert below the highway, while other culverts further up also direct water down the mountains.

When everything works properly, water flows easily away from Highway 1.

But after a blaze of the Dolan Fire’s scope, there’s a definite risk of drainage issues, according to Jason Kean, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Landslides Hazards Program.

Kean was part of a team that mapped the Dolan Fire in 2020 to assess where trouble spots and debris flows might erupt in the burn scar area. Researchers with that team considered burn severity, slope angles and even soil types to calculate which areas of the burn scar had a higher risk of debris flows, Kean said.

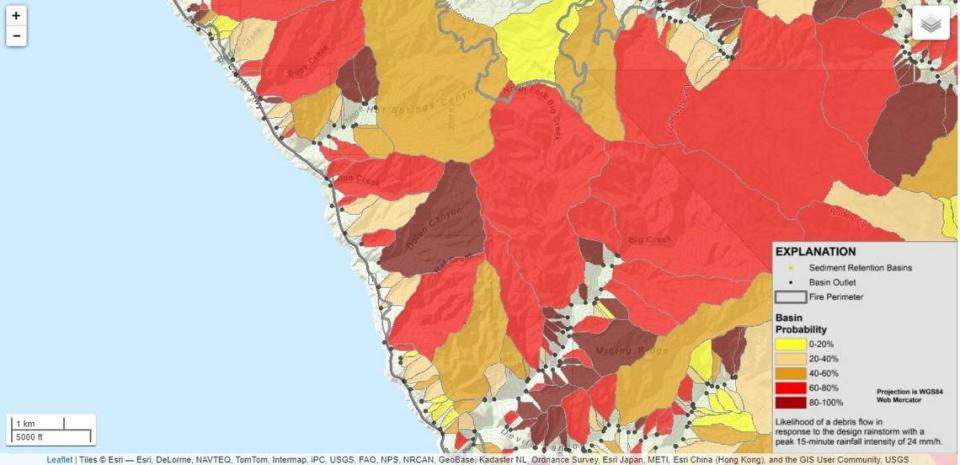

A map created by the team shows a mishmash of yellow- to burgundy-colored drainage basins, all ranked according to their likelihood of a debris flow given an average storm.

On the map, the Dolan Ridge basin is dark red, almost brown, indicating a high (greater than 80%) risk of debris flows given an average intensity storm. Right below it, the Rat Creek basin is bright red: 60% to 80% risk of debris flows.

According to the team’s calculations, Rat Creek had a 68% risk of having a debris flow under “a modest rainstorm scenario,” Kean said, meaning a storm dropping just under an inch of rain per hour.

Kean said the map’s data is used to help alert the Forest Service and Caltrans about potentially dangerous areas during rainstorms.

“This is a tool to get that info fast so that you can field check it on the ground,” Kean said. “And then people can start planning and be like, ‘OK yeah, here’s our hotspots in the fire,’ you know? — and Rat Creek was one of them — ‘These are the places we’ve got to really worry about.’ ”

Not all the places identified on the team’s map had significant debris falls, although many did.

In only one location was Highway 1 lost.

Stalled atmospheric river creates perfect mudslide conditions

First, take a region already prone to landslides. Add a massive burn that makes things slippery on steep slopes.

Finally, drop in what Shivers called a “tremendous amount of water over the course of a few days,” and you’ve got the makings of a disastrous situation.

In late January, the final ingredient was introduced: an atmospheric river that stalled right on top of Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties. At least one place received a whopping 17 inches of rain over a two-day period.

According to the National Weather Service, the nearest stations to Rat Creek reported between 8 and 9.4 inches of rain between Jan. 27 and 28.

The gathering water sweeping down the mountains pushed a sludge of rock, ash, mud, burned trees and other fire debris into drainage pipes in the area, cutting off its own escape.

Water pooled at the mouths of these clogged culverts, high up above Rat Creek, before spilling down onto the roadway below. Pictures from local residents show water and mud spreading across the road the morning of Jan. 28, though at that time, Highway 1 was still intact.

According to Shivers, at some point on Jan. 28, a rush of water and debris came spilling into the canyon with such force that it took a chunk of southbound Highway 1 down with it.

At first, it seemed that only a single lane of the highway was missing. A photo showing the missing chunk of the scenic byway quickly went viral online. But the next morning’s cool dawn light revealed that the damage was even more severe.

Both lanes of Highway 1 were gone.

Boulders, burned redwoods and mud: SLO County contractor talks cleanup

Randy Anderson, 63, of Papich Construction has seen plenty of mudslides in his day.

He helped clean up Big Sur slides in the 1980s, and was at Hurricane Point in the ‘90s. In 2018, he worked on the Montecito mudslide that swept through Santa Barbara in the wake of the Thomas Fire.

But he’s still shocked at the damage slides can leave in their wake.

Anderson, project manager for the San Luis Obispo-based company in charge of Rat Creek cleanup, was one of the first people at the Rat Creek mudslide on Jan. 29, after Papich Construction secured a $5 million emergency contract with Caltrans for the repair job.

“It looked like a bomb went off,” Anderson said, describing the Highway 1 corridor when he first arrived. “I mean about every canyon had a debris flow washing up onto the highway. In places you could hardly even get through.”

Anderson said Papich Construction began work the Saturday after the slipout, and has “been there even since in a cleanup mode,” removing gunk from the clogged culverts, cleaning off roadways and carting away the larger bits of debris.

Among the truck-fulls of wreckage, Anderson said he’s seen the fire-scarred ruins of massive redwood trees, five feet in diameter and 30 feet long, as well as boulders too large to be moved by heavy equipment. These rocks are instead blasted or put aside to be used in future roadwork projects, he said.

So far, Anderson estimated his company has removed about 60,000 cubic yards of debris from Rat Creek and the surrounding Big Sur area. When all is said and done, he estimates that number could be closer to 90,000 cubic yards.

That’s enough to fill roughly 30 Olympic swimming pools, or 450,000 standard bathtubs.

Caltrans’ estimate is more conservative. Engineers say Rat Creek alone has been the source of about 10,000 cubic yards of debris to date, and they estimate an additional 10,000 to 20,000 cubic yards still have to be removed.

The cleanup work is close to concluding, Anderson said.

If all goes as planned, he expects the cleanup will be completed by about mid-March. At that point, Papich Construction could begin to actually repair the road, though that is still pending a project plan from Caltrans.

This could mean some even longer hours ahead for the workers at the site, Anderson said, noting that many have been working 12- to 13-hour days trying to stabilize Rat Creek so that things can move forward as fast as possible and the road can reopen.

“It takes a lot of work and dedication,” he said. “You know, the guys are doing a great job. I just give them the credit.”

North SLO County businesses doing well despite closure

The Rat Creek slide on Highway 1 has put additional pressure on the North Coast businesses that rely on tourists to help keep them on course.

Already, 2020 was a tough time for all those entrepreneurs, due to ever-changing COVID-19 guidelines.

Most of 2021 has been better. Holidays, weekends and good weather have brought big crowds to the North Coast, packing parking areas, sidewalks and recreating areas with visitors.

The late January storm put that progress temporarily on hold. But after a week or so of cleanup and utility repairs, things seemed to go back to normal, with lots of folks traveling and visiting despite the Highway 1 closure.

Mary Ann Carson, executive director of the Cambria Chamber of Commerce, said Friday that she believes the North Coast “has been found as a destination, in and of ourselves.”

“We’re not just dependent anymore” on visitors driving to or from Big Sur, Monterey and the Bay Area, or going to Hearst Castle in San Simeon, which has been closed for almost a year, due to COVID-19 restrictions, she said.

“People have discovered our fresh air and outdoor activities, walking on the beach, hiking,” Carson said.

The convergence of the Lunar New Year, Valentine’s Day, the Presidents’ Day weekend and Mardi Gras brought hordes of people people to the area.

Many North Coast businesses, lodgings and restaurants were slammed, according to reports during the Feb. 17 North Coast Advisory Council meeting.

At least three restaurants ran out of food on Valentine’s Day night, according to council business representative Aaron Linn of Linn’s Restaurant, despite the fact that the eateries still can only serve their customers outside or offer take-out.

“It was busier than I’ve ever seen it,” Linn told council members, adding that handling that volume of orders under those conditions was “difficult.” “I’ve never seen that volume of business go through Linn’s. We handled it, and didn’t run out of food.”

According to Linn, staffing is an issue for local businesses that are gradually bringing back laid-off or furloughed workers.

When business picks up that drastically, that fast, he said, “You can’t manufacture employees.”

“Everybody is having to adapt all the time, doing the best they can,” Carson said. “Everybody is trying, that’s the good news. I really think it’s remarkable how well our businesses have managed to stay going. I’m very proud of them all.”

How long will Highway 1 be closed?

Now for the $5 million question: How long will Highway 1 be cut off?

There are two closure points on either side of the slide: the northern closure, located just above Lime Creek Bridge, and the southern closure at Big Creek Vista Point.

Those areas are currently under construction themselves, to create more permanent turnarounds points for people driving along the highway.

Meanwhile, cleanup at Rat Creek continues.

“There’s a lot of other work that needs to be done,” Shivers said, noting that site engineers are still assessing the area of the slide and cleanup.

Only once the assessment is completed can Caltrans begin to make plans for how to actually repair the roadway, he said.

The fluidity of the situation makes it almost impossible for Caltrans to establish a timeline as to when the road might fully reopen.

“It’s challenging work, but I think the track record is that we will come up with a project that will be viable, and at some point we will get this highway open,” Shivers said.

Would Caltrans ever give up on fixing Highway 1, and simply leave it unconnected?

No way, Shivers said. “That’s simply not something that we talk about,” he said.

Between the travelers who come from around the world to experience the beautiful drive and the Big Sur area businesses and residents who rely on the road as their lifeline, Highway 1 “is simply too important,” Shivers said.

Asked why he thinks so many are drawn to the highway, Shivers said, “It’s freedom. Beauty. Timeless. Spectacular.”

“The attention that this highway gets in this part of California is deserved,” he said.

With a sweep of his hand, Shivers gestured past the noisy hubbub surrounding the giant hole in the ground to the serene coastline just a few miles up the road.

There, you can see mountains dropping off into the Pacific Ocean, waves methodically lapping along the rocks. High up above, tall pines brush the bright blue California sky as birds swirl across it at much the same speed as the waves crashing below them.

“You simply look around and see what’s here,” he said, not without a hint of awe. “It’s worth experiencing.”

Now, it’s up to Caltrans to return that experience.