First person: Finding peace with my mom took decades, and now I miss her every day

My mom could irritate the daylights out of me.

“Are you having another Hate-Your-Mother Day?” she would ask whenever we butted heads as I was growing up. But I loved her as fiercely as she loved me.

I struggle now to remember what we fought about. I know I wanted the cotillion dresses she made me to be shorter. I also remember a Saturday morning when she called to ask what I was fixing my brothers for lunch.

“Nothing,” I said.

“Oh, Janet, don’t be like that. I used to fix my brothers breakfast, lunch, and dinner and wash and iron their clothes.”

“Yes, but they were working on your farm in Cuba. My brothers are watching TV.”

My friends must have grown tired of my moaning, “My mom is the most interfering, guilt-trip-laying, controlling person I know!”

When I was in middle school, however, a week before summer band camp, I addressed envelopes to myself for each day I would be gone and made her promise to write every day – starting three days before I left so that I would have a letter from her when I arrived.

And although I couldn’t wait to get away by the time I graduated from high school, when my parents drove off after taking me to Florida Southern College in Lakeland — a mere three hours away — I cried.

My college years were turbulent. I transferred from FSC to the University of Florida, then back to FSC. And when my parents learned that I had developed an eating disorder, they made me come home and attend Palm Beach Atlantic College.

I loved PBA but, once again, hated being under Mom’s thumb. Too many of our conversations began with her saying, “I don’t want to tell you what to do, but …”

While I was playing basketball at South Olive park one evening, she pulled into the parking lot and yelled across the soccer field, “Janet, go home right now!” It was no later than 8 p.m., and I was a junior in college.

After I married in 1986 and moved into my own house, one day I noted how many times she called.

“You called 14 times yesterday,” I told her as gently as I could the next day. “Instead of calling every time you think of something, why don’t you write it down, and when you have a long list, call me?”

“Fine,” she said, crying. “I’ll never call you again. I’ll never come over again. I’ll move far away, and you’ll never have to see me again. I don’t know why you hate me. All I’ve ever done is love you.”

Before cell phones, Mom would call the English teachers’ workroom at John I. Leonard High School and ask to speak to me. Thinking it must be an emergency, whoever answered would walk to my classroom and stay with my students while I walked back to take the call: “Do you suppose you could have dinner with us tonight? I saw a beautiful roast at Publix and put it in the crockpot with some potatoes and carrots.”

Saying, “Mom! You cannot get me out of class to ask if I can have dinner with you!” led to more hurt feelings and tears. And changed nothing.

Before traveling, Mom always reminded me where her will was. Whenever I said, “See you tomorrow,” she replied, “Lord willing.”

Ten years ago, when she was 81, she texted, “I should be dead by December, and I need to get ready. I need your help, but since you’re too busy to answer your phone, don’t worry. I will somehow manage by myself.”

She had been threatening to die since she was 40. Sadly, I knew that one day she would. She texted me the name of the pastor she wanted to speak at her funeral, the person she wanted to sing, and the hymns she wanted sung. She also wrote names on items she wanted others to have.

Divorce drama

The most stressful period of our relationship came when I was going through a divorce in 2012. Mom thought I was making the biggest mistake of my life. Relentlessly and without boundaries, she pressured me to remain married. I became so stressed that my voice was affected.

An ear, nose, and throat specialist recommended that I see a speech pathologist, who suggested that I talk to a therapist.

It didn’t take the therapist long to determine that the problem with my voice was related to the issues I was having with Mom.

What I wanted most for Mom was for her to be happy, and I knew that what made her happiest was her family. But she was unintentionally pushing us away. Once, at Sweet Tomatoes when I was in my 50s – with a table full of family and friends – as I was about to bite into a muffin, she snatched it out of my hand, told me I had no business eating it, placed it on a dish, and slid it out of my reach.

My therapist helped me realize that although I couldn’t change Mom, I could change myself. And just as I wanted Mom to accept me as I was, I needed to accept her as she was. I also needed to set boundaries and stick to them.

This didn’t mean that I could get Mom to stop pressuring me to remain in a dead marriage. It meant that when she did, I had to say, “Mom, we’re not going to talk about that, remember? If you’re going to keep talking about it, I’m going to have to hang up [or leave, or you’re going to have to leave].”

Also helpful were role-playing with my therapist, understanding the difference between “Mom is driving me crazy” and “I’m allowing Mom to drive me crazy,” shifting from needing Mom’s approval to wanting it, and following my heart instead of caring so much about others’ opinions.

'Energizer Bunny'

In April 2013, five months after my divorce, Mom went into cardiac arrest while having a stent put in at Bethesda Heart Hospital in Boynton Beach. Thankfully, she was resuscitated. But a week later, as I was feeding her broccoli cheddar soup from Panera, she had a stroke.

A month later, when Mom begged her doctors to let her go home for Mother’s Day, they acquiesced. It was impossible to say “no” to her when she smiled sweetly and batted her big, brown eyes. But I feared her doctors were letting her go home to die.

Any time I asked what she wanted for her birthday, Christmas, or Mother’s Day, she said, “to be with family.” Still, I tried to get her a thoughtful gift. But what do you get your mother when you think she’s dying?

“It’s a Small World” was her favorite ride at Disney World, and she loved Raggedy Ann dolls. Oh, blessed Internet! I found a wind-up Raggedy Ann doll that played “It’s a Small World.”

My brother Steve nicknamed Mom the “Energizer Bunny” because she didn’t die as we feared. In fact, she kept on going for seven more years.

She became a great-grandmother to three boys, taught Sunday school at Family Church downtown, hosted big family Cuban Christmas Eve dinners complete with Santa and piles of gifts, visited the sick and dying, attended funerals, helped those in need, took care of my dad, put flowers on loved ones’ graves, tried to remember everybody’s birthday, and worried.

One of Mom’s primary love languages was worrying. Although her worrying was annoying, I took pride in the fact that my mom could worry better than anybody else’s.

She would often call and say, “Your dad has been gone for an hour. Don’t you think we should go out looking for him?”

“Where would we look, Mom?”

“I don’t know, but we could at least drive around.”

More often than not, I would return from working out and swimming at the YMCA to multiple voicemails: “Janet, where are you? I’ve been trying to reach you, and you’re not answering your phone” and texts from my son, daughter, and son-in-law: “Call Grandma. She’s ready to call the police.”

Never enough time

Whether I spent one hour or five with Mom, it was never enough: “Can’t you just sit and talk for a minute? You’re always in such a hurry.” And she was forever in need of a hug. I’m grateful for all the times I did sit and talk and for all the hugs I did give her.

My son and daughter commented on how patient and loving I had become with “Grandma” and what a good daughter I was. My son even nervously asked, “I don’t have to do all this for you when you’re old, do I?”

Mom was happy for me when I fell in love and got engaged. Together, she and I shopped for my March 21, 2020, wedding.

The day before the wedding, I talked to her, as usual, several times. The second to last time, she complained that she was nauseated — something she had been complaining of all week. I told her to take the Alka-Seltzer I had gotten her. She said she didn’t know how. I told her I thought she was supposed to dissolve a couple of tablets in water. I didn’t offer to come over, even though my parents’ house was five minutes from mine.

Dad’s health had deteriorated since he broke his hip in 2017, but with my help and a daily caregiver, he and Mom were still living independently.

Mom had gotten her hair and nails done for my wedding, and I had hung Dad’s suit and Mom’s dress out for them. The last time Mom and I talked, she asked if I was ready for the wedding. Although there were only going to be 10 of us at my daughter’s house, I told her it was going to be a beautiful wedding — nothing but the best for her daughter.

“My daughter does deserve the very best,” she said. Then I told her I hoped she would get a good night’s sleep and feel better. I reminded her that her baby boy, my brother Steve, who was 57, would be coming from Naples in the morning and would drive them to the wedding.

At 4:50 that afternoon I saw that she was calling, but I was busy and didn’t answer. She didn’t leave a voicemail, which was unusual, and I didn’t call back.

The next morning, I went for a quick bike ride. I thought about stopping to see how she was feeling but didn’t. Instead, I called. Dad, who used a walker to get around, answered and said he would check on her. A minute later, he called, panicked, and told me she was on the bathroom floor.

The final goodbye

I was there within five minutes. My heart broke when I saw Mom’s lifeless body and touched her cool face, which was beginning to discolor. I called 911 and told the woman who answered that I thought my mom was dead. She asked if she should send an ambulance.

“Yes!” I said, hopeful for a moment. “She could be alive!”

Then, remembering that she had a do-not-resuscitate order, I started to sob. While the paramedics were there, I had the presence of mind to call the photographer my fiancé and I had hired for our wedding to stop her from driving from Ft. Myers. I also called Publix’s bakery and stopped them from baking our wedding cake.

Then, while Dad — who had been married to Mom for nearly 64 years — sat, looking forlorn, in his recliner by the front window and watched, I stepped outside to catch a final glimpse of Mom’s body being carried out of the home in Lake Clarke Shores that she and Dad had lived in for over 50 years, the home they had bought for $23,000 when I was in the second grade.

I wrapped my arms around one of the large, round, concrete porch columns and wept.

That afternoon, I realized that I had been pressing my right hand over my chest all day, as if doing so would hold my shattered heart together. And that evening, my back went out, causing me to throw up and leaving me incapable of even the slightest movement.

The tears that I would cry for Mom eight months later, on my rescheduled wedding day, would be tears of sadness that she wasn’t there and of happiness that she died knowing I had found someone I loved and who loved me and would take care of me.

I think about death more often myself now and have decided that the death of every person Mom loved — and there were many — taught her to love and worry as fiercely as she did and to try to control what she could.

My heart longs for Mom, especially when my phone doesn’t ring, when I want to tell or show her something, when I go anywhere we went together, and on special days.

My heart is warmed when I see something she would have liked: a butterfly, an orchid, a seashell. When I listen to one of her CDs of hymns. When I consider the many gifts she gave me — not just material gifts but the gifts of her love, wisdom, prayers, friends, the example she set. My education, memories, and brothers. The skills she taught me.

Several months after Mom died, I was devastated to discover that by cleaning my iPhone to create more storage, I had erased all my voicemails. Then I noticed that — inexplicably — a single voicemail remained: “Good morning. Happy birthday, my baby girl. Have many more, many beautiful ones. We love you. Happy birthday.”

My only message from her on Facebook Messenger is just as special: “You’re beautiful and a great daughter. We couldn’t do it without you. We love you. Thanks for all you do.”

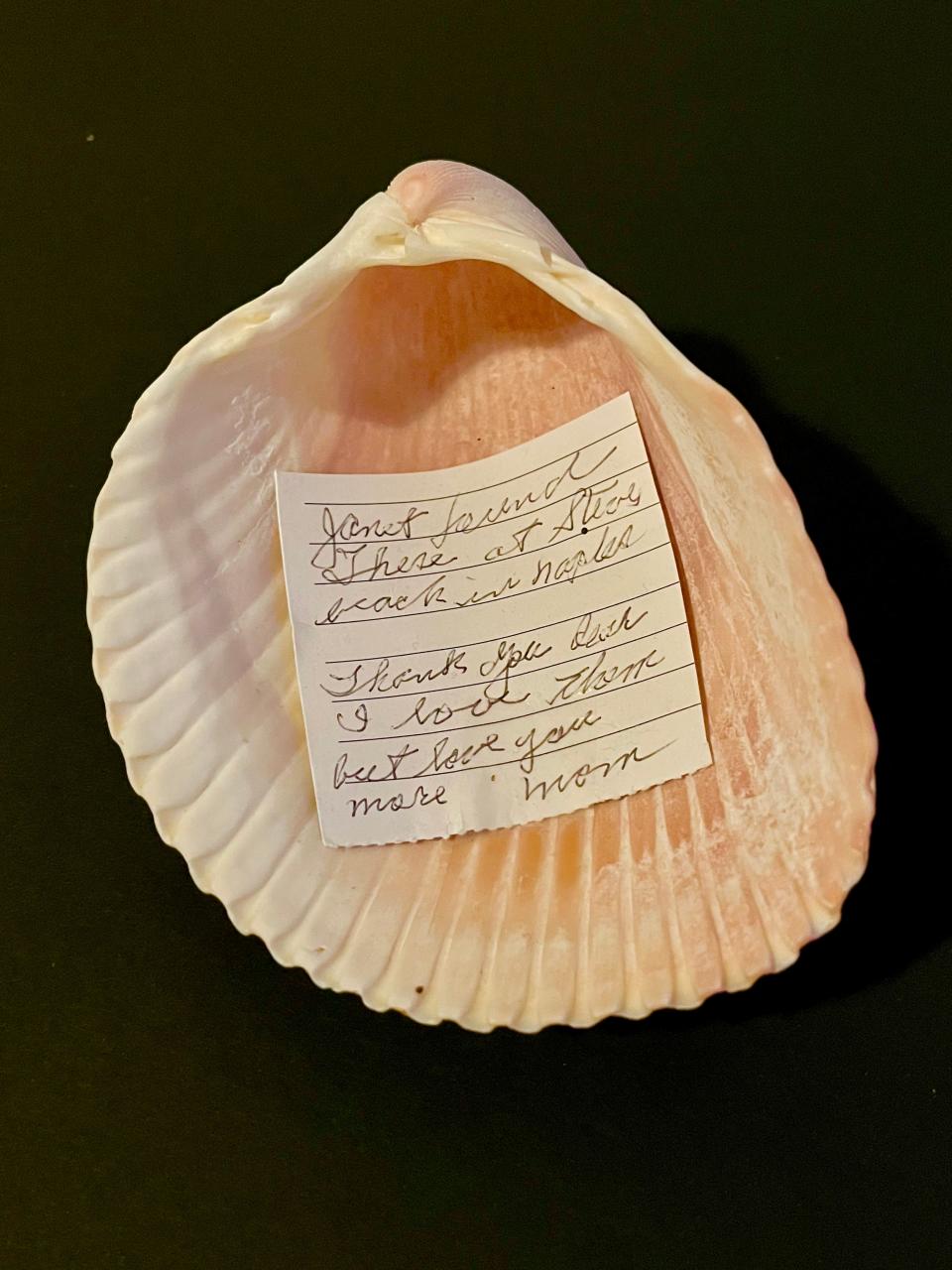

And I’m convinced that Mom taped this note inside a seashell because she knew I would be the one who would end up cleaning out the house where I grew up: “Janet found these at Steve’s beach in Naples. Thank you, dear. I love them but love you more.”

I love you more, too, Mom, and I miss you every day.

Janet Meckstroth Alessi has been teaching at John I. Leonard High School since 1983 and is a frequent contributor to Accent. She can be reached at jlmalessi@aol.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Mother's Day a reminder that my mom is with me always