First person: How I moved from grief and guilt to holiday healing

The holidays are traditionally a time to celebrate family and togetherness; but they can also be filled with painful memories and feelings of regret and guilt.

In the aftermath of my mom’s death in 2020, I tried to focus on being grateful that she lived as long as she did (six months shy of 90), that we had healed our complicated, sometimes fraught relationship, and that she loved and appreciated me. Her last written message to me was: “You are beautiful and a great daughter. We could not do it without you. Love you. Thanks for all you do.”

Yet, I kept circling back to what I hadn’t done her last full day of life – the day before I was due to be married.

More from Janet Alessi:First person: Finding peace with my mom took decades, and now I miss her every day

Alessi and pandemic challenges with Dad:Teacher recounts the difficult choices of caring for her failing dad in midst of a pandemic

Mom had been complaining of a stomach ache; but instead of driving five minutes to her house to check on her, I advised her to take Alka-Seltzer. And, although I talked to her several times the day before she died, I didn’t answer the last time she called. Nor, did I call her back.

The pangs of guilt piled on from there.

Mom and I once attended a funeral followed by a catered reception. On the way home, she said she wanted a similar service and reception after her death. Instead, I was secretly relieved when COVID-19 – declared a pandemic 10 days before she died – spared me from having to plan and hold such a grand event when my heart and eyes were swollen with grief.

And this: When Mom was alive, she took flowers to her parents’ and siblings’ graves on holidays and birthdays. I knew she would have wanted me to do the same for her; but I hated visiting her grave and went only twice the first year after her death – and I didn’t take flowers. I didn’t see the point. While there, all I could do was picture her in her coffin and cry.

I grew up believing in God and Jesus and heaven, but after finding Mom dead on her bathroom floor, seeing and touching her body in her open casket, and knowing her casket would be lowered into a hole in the ground, I struggled with my faith. It’s easier to believe in God when looking at a newborn baby, the ocean, a butterfly, or a zebra than when staring at death.

The beginning of the end for Dad, too

A year after losing his bride of nearly 64 years, Dad – 6-foot-1 and 230 pounds – became bedridden.

But I was not in top shape either. Recovering from my second hip replacement, I was using a walker. I had a bad back to boot. I didn’t see how I could take care of him, and I feared I wouldn’t be able to find reliable home health care.

But I didn’t even try. Instead, I did what nobody wants to do: I put my dad, who had always been my rock, in a nursing home.

Due to COVID prevention measures, Dad’s nursing home required an appointment to visit, didn’t allow me in his room, and discouraged me from visiting more than once a week.

I knew he didn't like it there. He complained, "If I nicely ask the workers to please do something, they should try to help me, not ignore me." He said his pleas were often met with, "That's not my job" or "I don't know how to do that." I was frustrated with the staff too. Once he was accidentally locked in the nursing home's conference room by himself for a half hour. They also cut him so badly while shaving him that I became his barber.

But, afraid that other nursing homes wouldn’t be any better, I didn’t investigate moving him – which became a “should have” that became a regret that turned into guilt.

Dad lost the ability to make calls and answer the phone, but a sweet aide called me every morning and handed him the phone.

He lasted seven months in the nursing home. The morning of the day he died, I was told that, for the first time, I would be allowed to visit without an appointment – and in a room instead of the lobby or cafeteria.

But rather than go to the nursing home that morning, I went to work.

Why? I was told Dad was “unresponsive,” so I assumed he wouldn’t know I was there. I’m a teacher and knew I wouldn’t be able to get a substitute on such short notice – we struggled to get one with even a week’s notice. Also, a newspaper photographer was coming to my classroom that day for a story.

And, though Dad was the one who taught me to be frugal, this reasoning haunted me more than any other: I didn't want to burn sick time; if I don’t use those hours, I will get paid for them when I retire.

During my lunch break, Dad’s aide called and handed him the phone. I couldn’t make out what Dad was saying, but he was trying to talk − he was not unresponsive. I told him I was sorry I wasn’t there and would be soon.

Even though I was crying, and Dad was dying, the photographer was due to arrive in minutes, so I waited. As soon as he left, I divided my students among my coworkers and called my daughter, Christina, to meet me at the nursing home.

But why had I waited?

I held Dad’s hand, and Christina and I told my dad – her grandpa and No. 1 fan – how much we love him. We reminisced, laughed, and cried. I told him how proud I was of him. I believe he knew we were there because he gripped my hand, and when the hospice nurse asked us to leave so that she could clean him, he didn’t want to let go.

Thinking that Dad could linger for days, I asked the nurse if she thought Christina and I could get something to eat. She said, “Yes.” He died moments after we returned.

Why hadn’t we stayed?

Feeling the pain of 'firsts' without loved ones

For the past several years, I’ve summered in New Mexico, where my husband, Otis, has a house. This past summer, I spent all of June and July there. Otis found me crying on the day before I was to head back to Florida.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“This is the first time I don’t have a parent who will be happy that I’m home.”

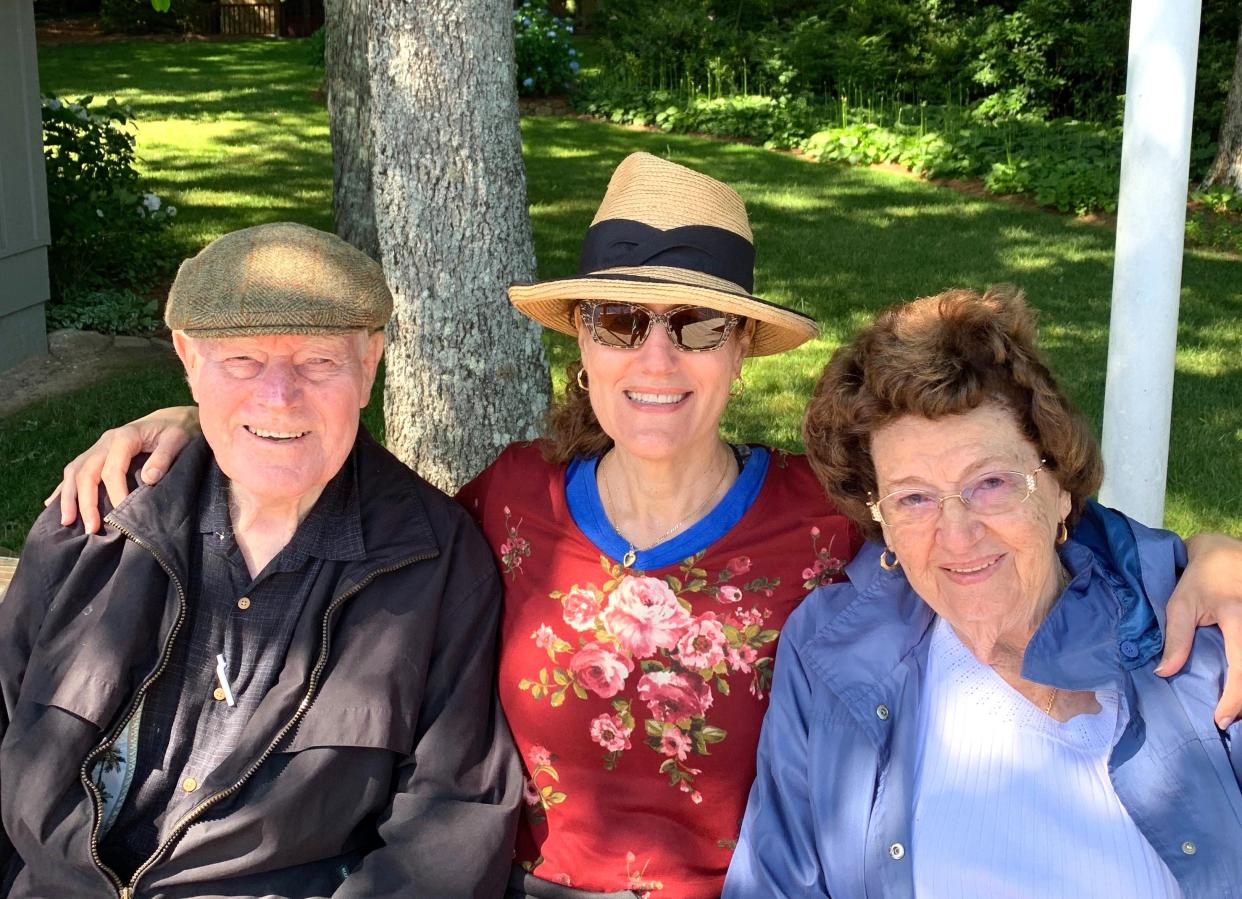

By the end of my parents’ lives, our roles had reversed. I was taking care of them. In a sense, losing them felt like losing my parents and children. They had also become my best friends. When Otis was in New Mexico, my parents and I were The Three Musketeers – albeit with a cane, walker, and wheelchair and parking in handicapped spaces.

Unable to shake my melancholy after returning from New Mexico, I put a beach chair in the trunk of my car and drove to my parents’ graves.

Several people have told me they talk to their deceased loved ones. I was glad that was working out for them but didn’t see the point. Still, sitting in my beach chair, I gave it a try.

I told Mom and Dad about my summer. I caught them up with my life, my brothers’ lives, our children’s lives. After telling them how much I miss and love them and having a good cry, I felt much better.

In September, Otis became concerned when I told him that twice that week, while I worked out at the gym, tears rolled down my face. Fortunately, no one noticed.

As my fellow gym rats focused on building muscles and taking selfies, I focused on three days in the previous October: the 17th, my dad's 92nd birthday, when he was barely conscious enough to eat the blueberry pie and ice cream I fed him. The 18th, the day he died. And the 20th, my first birthday without him.

October had always been my favorite month, but now, as 2022 was coming to a close, I was dreading it.

Words of wisdom lead to acceptance and healing

The next morning, Otis texted, “You’ve expressed remorse for your actions / inactions many times. I see that as undeserved guilt. Stop punishing yourself and recognize what a great daughter you were. Nobody did more for your parents than you. Ask for forgiveness, pray, and realize that we’re all fallible, and you did your best.”

I heeded my husband’s sage advice and asked God to please get Mom (who was probably talking) and Dad (who was probably eating ice cream) to listen to me for a few minutes. I told them why I felt guilty and asked them to forgive me. None of the reasons I felt guilty matter to them. They love me, are grateful for everything I did for them, and want me to be happy.

Then, realizing that we can’t base every decision on every possible scenario and that nothing good had come from hanging onto my guilt – I forgave myself.

The next day, I watched the DVD that the funeral home had made for Dad’s funeral. As it ended, I noticed that I was smiling because in every picture of Mom and Dad, they were smiling, which reminded me that they had lived rich, full lives.

Until they no longer could, Mom and Dad drove north every fall to see the leaves change. So, a week before Dad’s birthday, I took some fall leaves and flowers to their graves, where – for the first time – I was able to enjoy the tranquility of the cemetery.

On his birthday, Christina, my older brother, his wife, and I celebrated by having some of Dad’s favorites: Russo’s subs, Fritos, root beer floats, pie, and ice cream. (Yes, he somehow lived to be 92 on that diet.)

Every Christmas, Mom and Dad would buy a dozen poinsettia plants and give me one; so this year I’ll be taking poinsettias to their graves.

Time may heal all wounds, but forgiving ourselves for our shortcomings – both perceived and real – helps, too.

Janet Alessi has been teaching at John I. Leonard High School since 1983 and is a frequent contributor to Accent. She can be reached at jlmalessi@aol.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: How I moved from grief, guilt to holiday healing after my parents died