First She Was Raped as a Child, Then Bad Got Worse

By the summer of ’81, the warring in my head was near constant. I had sharp memories about the day I was raped, and, at times, I awoke screaming in the dark. I was afraid to go outside, went days without bathing and rarely ate. My tangled, unwashed hair fell out in clumps. I don’t remember crying or even talking much. I mostly kept to myself. It was safer that way, I thought.

I was scared that somebody might touch me.

Me and Mama were like ships passing in the night until the day I used a razor blade to arch my eyebrows. In a bizarre attempt to look like Farrah Fawcett, I also used a hot comb to straighten my hair and lopped off the front left section with a pair of her sewing scissors. I wanted feathered bangs like the white girls at school. I nicked my eyelid with the razor.

When she got home from work that night, she took one look at the blood trickling down my face, shook her head, and hauled off and slapped the daylights out of me. Cowering in the corner, I hollered out for my father.

“What did you say? What did you say?!”

“I want my daddy! I want my daddy! I want my daddy!”

I wanted her to hear me. I wanted her to feel my rebuke. I shouted it over, and over again, until she jammed her finger in my face and screamed, “Your father is dead! And he ain’t never coming back!”

My Childhood Rape and My Life That Might Have Been

Mama was bleary-eyed and angry, angry that he’d left her and angry that I’d unwittingly hurled his murder in her face. She unwrapped a fresh razor blade, tossed the white paper, and tilted my head back. By the time she was finished, I had a few wisps of brow hairs left.

When I think about how small I was and how little I understood about the world, I admit, it’s easy to be angry now. Trembling and scared, I wanted something different. Our world was full of slapping, drinking, cussing, and shooting. I wanted at least a pleasant house and a pleasant family like the Farrells had.

I cried myself to sleep.

One Saturday morning, Mama woke me early, told me to pack a bag and drove me to Auntie Gerald’s house in East St. Louis. She said little along the drive as she listened to the news on public radio. It was supposed to be another weeklong visit.

No matter how much time I spent living under my mother’s roof, for as long as I could remember, the house on Tenth Street had always felt like home. Despite having paid every debt he ever owed on time, and proudly serving his country in the U.S. Army, in 1969, Uncle Ross was Black and, thus, could not qualify for a bank loan. He was forced to take out a contract-for-deed mortgage, a high-interest predatory agreement backed by real estate investors out to profit off redlining.

Situated along the easterly banks of the Mississippi River in central Illinois, East St. Louis was once predominantly white. A massacre unfolded in 1917, ignited by labor disputes, when white people feared they would be forced from their well-paying jobs in nearby factories by Black migrants who emerged from the South beginning in the late 1800s. In the end, an estimated two hundred fifty black people were killed and approximately six thousand were left homeless, burned out of their brick bungalows and rooming houses.

When it was over, remaining residents picked up the pieces. The mayor pushed for reparations, paying white people for the property they lost to the fires and forcing insurance companies to pay out policies held by Black residents. Civil rights leaders came to town, mounting investigations into the massacre. But, otherwise, the city would go on about its business as one of the nation’s most important stops along rail lines and barge routes.

However, white people began to abandon the city—first in trickles, then in droves as more Black people were drawn to its seemingly boundless economic opportunities. Between 1967 and 1970, nearly every remaining white family left East St. Louis for the suburbs.

Four decades before Uncle Ross put his name on the deed, the city lines were redrawn. The smokestacks and factories at the edge of town were de-annexed around 1926, so the companies wouldn’t have to pay taxes into an increasingly Black town. That year, the City of Monsanto—now named Sauget—was incorporated just south of town. National City, to the north, was home to the St. Louis National Stockyards Company. Industry swelled and, by 1945, it was called the “Hog Capital of the Nation.” At one time, there were forty-three packing plants processing upward of one hundred thousand head of cattle and hogs a week.

The house sat well within sniffing distance of the putrid-smelling stockyards. By the time Auntie Gerald and Uncle Ross moved in, only a single white family remained on the block in the Exchange–N. Fifteenth Section of the city. Originally built in the late 1800s, there were three well-laid bedrooms, not counting the squat room in the basement, and a single oversize bath where Auntie Gerald hung up decorative towels that nobody ever dared dry their asses with.

When the expansive front porch could use a few well-placed nails or the living room needed a fresh coat of paint, Uncle Ross did all the work himself. Every Memorial Day, Veterans Day and Fourth of July, the man who once boosted his age by two years to qualify for military service on behalf of a country that didn’t think he was worthy of pissing in a bathroom stall next to a white man or sharing the same water fountain, would proudly hoist an American flag into its place on the center porch pillar. He hung an English red cedar porch swing along the far-left end, suspended by cast-metal chain links attached to S-hooks, and planted shrub roses along the front edge.

When we got to Auntie Gerald’s house, my cousin Booky met our car at the curb. We took off down the street toward the corner store. There were new owners by then. The Cochrans from across the street rented the shuttered store, reopened it, and installed a Pac-Man machine in hopes new customers might also spend money on overpriced cans of Vess soda, single rolls of toilet paper, loose cigarettes and Red Hot Riplets potato chips. They sold the spicy pickles my cousin Bug adored so much from a jar on the counter and let her have the leftover juice. Along the way, we passed a woman sitting in a fold-out lawn chair on the porch of a duplex. I was all at once alarmed and amused, if not insanely curious. Miss Whatever-Her-Name-Was was buck naked from the “rooty to the tooty,” hooting and hollering like she was watching some funny picture show that only she could see. Skinny as a beanpole, her little brown children, one of them wearing nothing but a diaper and a nose full of snot, scampered around the yard while their mama’s slack titties swayed in the wind when she let out a laugh.

She caught sight of me and Booky, and hollered out, “Y’all going to the stow? Bring me sumpin’ back, hear?”

She disappeared into the house.

“Did you hear what she said?”

“Don’t know and don’t care,” Booky said, “and you shouldn’t either, Go Go.”

Plenty of folks had been hit running across Tenth Street, which was deemed a state highway back then. I worried about the children in the yard.

“Who’s watching her kids?”

“What did I just say? Them her kids.”

“Okay, but she wasn’t wearing any underwear!”

At the store, we had to wait in line behind a twentysomething white lady, which was strange in and of itself. She was yelling at the cashier because they didn’t have a business license and wouldn’t take food stamps as payment.

“This is money!” she said waving the stapled booklet in front of the Plexiglas window. “You out here breaking one law. Who gives a good got-damn if you break another one?”

We waited our turn, then bought a sack full of Now & Laters, Chick-O-Sticks and Mary Janes. On the way back, I noticed the kids were gone and there was no sign of the naked lady or her husband when we passed again. The woman on the porch was an addict, I would later learn. We sometimes saw her roaming the block, making it up to the corner of Tenth and Pennsylvania before her husband, beset with the same addictions, took her home.

“Who was that white lady in the store?”

“You know they be tricking over in those apartments.”

“What’s tricking?”

“Hoeing.”

“What’s that?”

Booky chuckled and said, “Here, Go Go, shut up and eat a Chick-O-Stick.”

We spotted Old Man Ford coming out the alley and took off running down the street. He haunted the numbered blocks between Summit and Pennsylvania Avenues, carrying an empty five-gallon paint bucket and a brown, sawed-off broomstick. He’d raped one of the girls from across the street and everybody knew he’d strangled Miss Cherry, the blind shopkeeper, to death.

He never made it to jail. Somebody said he was found dead in the alley behind the Sanders house. He’d been back there in the weeds for a long time, they say, the stench of his decomposing body masked by the odor coming out of the stockyards.

When we got back, Mama was gone. I was used to my mother coming and going without so much as a “hello” or a “goodbye,” so I thought nothing of it at the time. It was a week or more before my mama came back. She called me out to the car. Dressed in her work clothes, she seemed to be in a hurry.

“Take this stuff in the house.”

My clothes, stuffed into brown paper bags from the grocery store, were piled into the truck.

“How long am I staying here?”

“As long as I say so.”

She didn’t stay but a few minutes, just long enough to trade pleasantries with Auntie Gerald and hand her a check, which my aunt folded and tucked into her brassiere.

Even then, as my mama backed out of the gravel driveway, I did not realize what was happening until I overheard my cousin Bug tell somebody on the telephone that I’d been “dumped.” I ran upstairs and locked myself in the bathroom. That’s when I noticed my shorts were soaked in blood. The first full menses came on like a rolling mudslide.

“You so smart you stupid,” Bug said. “Your mama didn’t tell you nothing about getting your period?”

“I’m not stupid. I know what a menstruation is. I guess you do, too.”

Bug was twenty and her son, Marceo, a burly stump of a boy who everybody called “Fat Man,” was five. She’d gotten pregnant at fourteen and went into labor a few months before her fifteenth birthday in 1976.

“Shut up before I bust you in your damn face,” she said, sneering.

Auntie Gerald handed me a bag of Kotex pads.

“Here, clean yourself up and put one on. And wash between your legs real good. Don’t get no blood on my floor.”

I put the thick white pad on upside down, the adhesive sticking to my pubic hair. A while later, when Grandma Alice saw blood running down my leg, she took me back into the bathroom and gave me a new one.

“Stick it to your drawers,” she said.

It was Uncle Ross, though, who took me into their upper bedroom and gave me “the talk” that night. He warned me about sexual contact during certain days of the month. Though he wouldn’t say exactly why, it all matched up with what I’d read in Mama’s medical book and remembered from Miss Seigel’s filmstrip. He was very clear about how a young lady should comport herself in public. He admonished me to dress modestly.

“Keep yourself clean, Red,” he said, “especially when your period comes on.”

Although he was quick to mete out discipline with thick leather belts and sometimes a souvenir wooden paddle from an amusement park, Uncle Ross was a kind man. We all knew the fullness of his compassion and never once doubted his devotion to us. Just as he’d promised Daddy, he eagerly stepped in my father’s shoes.

Auntie Gerald went to church three or four times a week: Sunday school, followed by morning and afternoon services, Wednesday-night prayer meetings, and choir rehearsal every Friday. Fifth Sundays were for communion, testifying and baptizing. Unlike my mother, her elder sister dressed modestly, never touched a drop of alcohol, and could cut a rug down to the padding. She never uttered an expletive.

For her part, my aunt was a marvelously plump woman who was shaped like a hedgehog and stashed money in her bosom. She cinched her hefty flesh with the triple-bolted girdle and, with the record player needle dropped on the right song, Mama’s Bible-thumping sister would swing and swag the Lindy Hop. My mother eschewed such displays of piety, weighed all of a hundred pounds on a full stomach, and couldn’t dance.

Most of the sweet footing went on in the formal living room next to the floor model, midcentury Zenith color television. Situated behind pocket doors and a grand entryway trimmed in ornate crown molding, the room also had wall-to-wall plush red carpeting, yellow-and-white embroidered sofas encased in custom plastic slipcovers and decorative mirrors on the textured damask wallpaper. The room was off-limits, except on holidays and sometimes Sunday if good company came over for supper. The whole thing smelled like Scott’s Liquid Gold furniture wax and Woolite rug cleaner.

Auntie Gerald, who integrated the staff at Norwoods Country Club on Lucas and Hunt Road in north St. Louis County, did the family shopping at Grandpa Pidgeon’s and a Venture store up on Collinsville Road, and sometimes at Famous-Barr in the sprawling mall over in Belleville. She called it “going up the highway.” She loved a Kmart blue-light special almost as much as she enjoyed cornbread soaked in buttermilk. She bought her groceries in bulk, including the box loads of chicken wings and hotdogs that she kept in a deep freezer alongside loaves of Wonder Bread. Every so often, we drove out to a farm beyond Cahokia Mounds to pick turnips, collards, and pole beans.

Uncle Ross lugged in the groceries, saw after the dogs and the yard, and burned the garbage in a fire pit when the city went bankrupt and stopped door-to-door trash collection, while my aunt wrung out the laundry and pinned our unmentionables on a clothesline out back. Uncle Ross didn’t believe in store-bought dog food or letting his mutts in the house. When the old hounds died, as they commonly did after diets of table scraps and spoiled meat, he buried them in plots around the back garage.

On a block possessed with rooming houses, prostitutes, and drug addicts, we seemed to be better off than most others, except the Sanders siblings—a white judge, lawyer, and librarian—and the friendly loan shark who lived across the street. After we might get caught up in whatever was going on out in the street, Auntie was a strict disciplinarian. Running in the house was forbidden, as were a lot of things, and getting caught either meant a tongue lashing or the business end of Uncle Ross’s strap. Which one depended on whether Auntie Gerald was around, in which case the punishment would always be more severe.

“A hard head makes for a soft behind,” she’d often say.

When she was feeling good, Auntie would laugh like a schoolgirl, an uncontrolled burst of glee that made her belly jiggle like a bowl of gelatin.

But, that summer, something in Auntie Gerald had changed. She seemed to be angry about everything and at everybody. She had a mean streak that ran as long and deep as the Mississippi. And, for the first time in my life, I was scared of her. The mere sound of my name coming out of her mouth was terrifying.

Every night, as the adults took to their rooms, me and a band of cousins gathered sheets from a closet and slept on the living room floor. Linens were on a first-come-first-serve basis and pillows were in short supply. Most nights, I was left with nothing. So, I started stashing my pallet in Grandma Alice’s closet hours before bedtime. I woke up that next morning soaked in blood and urine. Shame washed over me. I was afraid my cousins would see the bloody clothes and laugh at me. So, I sneaked upstairs, washed myself up, stuffed the wet sheets in a trash bag and tucked them into Grandma Alice’s closet. Later that day, I heard her calling me from top of the stairs.

“Goldie Taylor! Get your behind on up here!”

I was shaking when I entered her room. She was sitting on the edge of the bed. Bug was in there too, her arms folded and smirking.

“Let me tell you one thang,” Auntie Gerald said, jamming her fat finger at me. “You gone quit pissing on my floor!”

“I didn’t mean to.”

“Your mama didn’t say nothing about you pissing on yourself. You dern near thirteen years old. Piss on my carpet again and I’m gone bust your behind, you hear me?”

I nodded my head.

“Say, yes ma’am,” my cousin chided.

“Yes, ma’am,” I muttered.

“Pissy Annie,” Bug said. “That’s what we gone call you.”

“That’s not my name.”

“What’chu say, Pissy Annie? You sound like one of them hunkies out in St. Ann.”

“So what? That’s not my name.”

She dived at me, grabbing my neck with both hands. I felt my head hit the floorboards. I couldn’t breathe.

“Janice! Jannie-Bug, let that child go!” Grandma Alice screamed. “I said let her go!”

Bug kept choking me, tightening her grip, repeatedly banging my head against the wood slats until I blacked out. I vaguely remember somebody carrying me. I woke up that night in Grandma Alice’s bed. The house was silent. I got up and tiptoed downstairs.

Alone in the darkened kitchen pantry, among the stacked canned goods, the canisters of sugar, flour, and dehydrated milk, I braced the telephone on my shoulder. I knew the collect long-distance call would register on the next bill from Southwestern Bell, revealing the time and duration. Making long-distance calls, whether to St. Louis County or down to Florida, was strictly forbidden. It would mean another flogging and more chores. But, right then, I didn’t care about getting another whipping. I just wanted to go back to St. Ann. I was desperate to sleep in my own bed again, even if it meant being alone most of the time. While I still harbored a rash of resentment for Mama, I felt like an orphan and didn’t want to wake up to somebody else’s mother. The operator announced my name and connected the lines.

“Mama, please come get me,” I whispered.

“Do you know what time it is? What’s wrong with you?”

I heard the creaking floorboards. Somebody was coming up the basement stairs. The noise grew louder. I could hear their feet padding across the dining room now, just on the other side of the wall.

“Mama, please,” I said. “Please come get me.”

The line went dead. The first blow to my temple, a closed fist, knocked me into the shelving. I remember how it stung, then the numbness and sound of my screams filling my ears.

“Who was you talkin’ to?” Bug demanded to know.

I could feel myself trembling. Trapped in the small alcove, I braced myself against the shelving. “Nobody,” I mumbled.

I could taste my own blood, the salty tears.

“Who was you talkin’ to?”

“Nobody.”

Bug grabbed the receiver and reared back as if to swing it. I flinched. She laughed.

“Get-cho stupid ass out that closet.”

I stayed awake in the kitchen that night. Afraid to go to sleep, I didn’t crawl into my pallet until sometime near dawn.

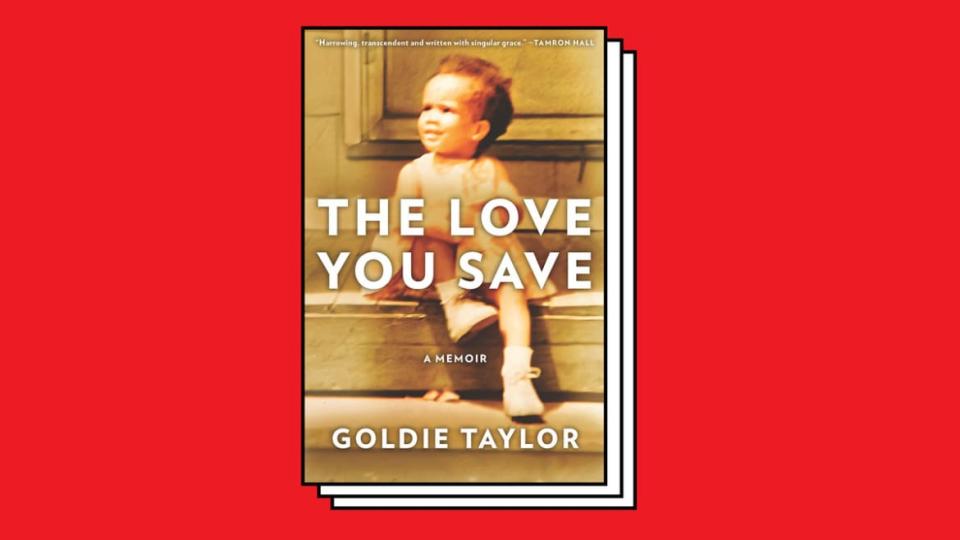

Excerpted from “The Love You Save” by Goldie Taylor; on sale Jan. 31, 2023. Copyright © 2023 by Goldie Taylor. Published by arrangement with HTP Books, a Division of HarperCollins.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.