First, they turned down the heat. Now Southwest chile growers want to build a better pepper

For the 10th anniversary of their family’s chile company, Reyna Lara wanted to do something special to honor their roots.

She found her answer in the family, more specifically in her father, whose face became the logo for their packages of dried chile peppers.

On it, Feliciano Lara sports a mustache, a bright white cowboy hat and a suit jacket, encircled by the words “Chiles Don Chano," incorporating his nickname. Sometimes, Reyna says, as they cross between their home base in Texas and their farm back in Zacatecas, Mexico, border patrol agents recognize her dad from the labels.

“You’re Don Chano!” they say.

The label was meant to be a temporary design, but it stuck because the customers ― particularly female customers, Reyna has noticed ― like it.

When Reyna and Feliciano Lara say Productos del Campo Lara Hernandez is a family business, that’s what they mean. They wax poetic when they talk about their chile farm back in Zacatecas. For them, it’s not just food, but part of their heritage. And the place where that food grows is their homeland.

Reyna translated for her father in a Zoom call, and when he started describing the farm, she stopped to email a picture. In it, orange clouds hover over a lush green field.

If you look closely enough, between the leaves, like bright jewels, you will see the chiles.

“The soil is red. It’s different, it’s red,” Reyna said. “The chile peppers taste different.”

It’s the taste of those chile peppers that fires up the passion of pepper growers like Reyna and Feliciano Lara, who want to do everything they can to be on the forefront of pepper innovation.

They and others in the industry will need that innovation going forward. Chile farmers, particularly those in the U.S., are facing many of the same challenges affecting other agricultural producers: labor shortages, rising wholesale costs, climate impacts.

It’s not for a lack of demand. Increasing interest in global cuisines and a pandemic that led more people to cook at home have both fed consumers’ desire to try chiles.

5,000 acres to foreclosed: How one family’s story shows the struggle of Black farmers

So Reyna and Feliciano, along with over 200 other chile aficionados, found their way to Tucson and Pearce in September for the International Pepper Conference. Reyna and Feliciano represented their company in hopes of learning about new technologies and methods that might help them expand their operation, which sells several varieties of dried chiles to stores in the United States.

At the conference, scientists, farmers and other pepper enthusiasts stood under the hot September sun to witness all manner of machines that can harvest peppers, zap weeds, cut stems and ground and dehydrate the colorful curved fruits into powders. Reyna says they just got a machine to automate their chile-bagging process, but they’re looking for techniques that might give them an edge in growing, manufacturing and distributing.

It wasn’t always so high-tech. First in Indigenous communities, and much later, in the early days of the commercial chile business, agricultural pioneers spent decades crossing chile plants in hopes of developing varieties that would produce the right flavor and zing.

And as breeders and salsa companies realized the potential in some customers’ spice-averse palates, they set their sights on developing a consistently mild pepper. Whoever could do that, one prominent pepper expert predicted, would “control the world.” And as they did, they patented multiple varieties of mild peppers to protect their unique properties.

Now some breeders and farmers believe the promise lies in a new era of health foods. Others think there could be value in returning to traditional, cultural roots.

Whatever the dream, farmers, breeders and scientists are trying to understand the people, the customers, behind America’s pepper cravings, and what they believe represents different visions of a changing culture.

The story of the mild chile pepper

Benigno Villalon is better known to many in the industry as Dr. Pepper, a nickname he picked up in the thick of his research when he accidentally gave another agronomist a sample of a pepper that was way hotter than either of them had intended.

Upon tasting it, Villalon said, the agonized agronomist, cried out, “some Dr. Pepper you are!” and the name stuck.

Villalon and his technicians were among the first to develop the consistently mild jalapeño peppers that big companies like Pace — as in Pace Picante Sauce — were after. His legacy is to ensure that accidental tastebud scorching happens less often.

Born in 1936 in Edcouch, Texas, seven miles from the border with Mexico in the Rio Grande Valley, Villalon grew up helping his family grow tomatoes, bell peppers, corn and cotton. They relied on immigrant workers from across the border who didn’t have official paperwork to be there, aware that the government turned a blind eye because their crops were going to the military, to help with efforts during World War II.

After he graduated from high school, Villalon swore he would never be a farmer. He and many of his classmates grew up with the military in mind, and he joined the Marine Corps, where he entered boot camp in San Diego before spending two years in Japan.

He married his high school sweetheart and they spent their honeymoon at Camp Pendleton in California. After three more years in the military and a brief stint at a factory, he was hired at the Texas Agricultural Experiments Station as a technician. There, he met plant breeders and pathologists who persuaded him to register in the agronomy program.

Villalon earned a bachelor’s degree in agronomy, a master’s in plant breeding, and a doctorate in plant pathology and virology. He took an assistant professor position at the University of Florida and then returned to Texas for a research position at his alma mater.

During the 1960s, he said, it wasn’t uncommon to see an entire field of bell peppers wiped out by viruses. Hot peppers were fickle and highly variable. In one field, growers could find peppers that weren’t spicy at all or peppers that could light the mouth on fire. The stems weren’t uniform, so it wasn’t easy to harvest them mechanically.

Soul food: What soul food means to this Southern chef around the holidays

That changed as researchers like Villalon found ways to improve the crops. He and other breeders used genetics to imbue the peppers with virus resistance, make them better suited for mechanical harvest, improve their flavor and nutrition and set their heat at more consistent mild levels.

Villalon says a representative from the processing team at Pace, the salsa company, came to him and said: “If I had a consistently mild jalapeño, I would control the world.”

It took 10 years to figure it out, but Villalon found a way to combine the flavor of the jalapeño with the consistently mild characteristics of other peppers like bell peppers. (Pace, for the record, said the company has a “rich history that spans back to 1947” and could not confirm details related to the creation of their mild salsa, though a New York Times article from 1982 suggested a “lucrative market” for Villalon’s new variety.)

And then, Villalon says, “all hell broke loose.” The processing demand became a phenomenon.

Some Mexicans got excited, but some got mad, Villalon said. “What are you trying to do? You're going to ruin our culture,” they cried. “Jalapeño’s supposed to be hot.”

But Villalon, whose grandparents sought amnesty in the U.S. and immigrated from Mexico in the 1920s during the Mexican Revolution, saw nothing wrong in his new variety. In his view, consistently mild peppers meant that more people could enjoy traditional foods that had previously turned off the more gustatorily sensitive.

The money didn’t hurt either. Pace Salsa (and other companies, though Villalon noted that Pace emerged as a big winner), “laughed all the way to the bank.” They began selling “mild,” “medium” and “hot” varieties of salsa that flew off the shelves. Sales skyrocketed, and by 1991, Pace’s mild “Picante” sauce was more popular than ketchup.

“We revolutionized the salsa industry with one word,” Villalon said. “Mild.”

Villalon appreciates the expertise of pepper cultivators in his family's native country and he gets a certain misty look when he talks about how many U.S. growers have never even been to Veracruz. Still, he sees his mild peppers as a success story.

And anyway, who would want to bite into the spiciest peppers in the world? Too much spice can desensitize nerve endings, and while young people can recover them, past a certain age, he argues, they’re gone forever. With peppers that don’t pack quite as much of a punch, more people can experience their health benefits and unique flavors.

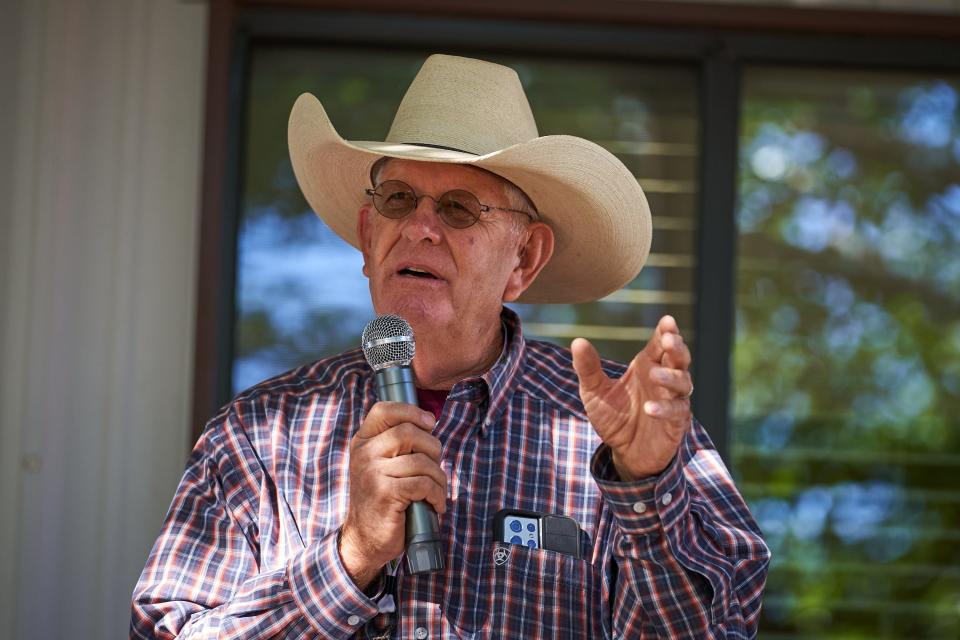

At the International Pepper Conference, Villalon cut open a sample pepper with his pocket knife, pointing out the specialized glands inside the pod that contain capsaicin, the molecule that gives peppers their unique sizzle. He sliced off a piece and tasted it. This one, he said, was definitely a milder variety.

What does he think about when he bites into peppers like this one?

He chuckled.

“Dollar signs.”

Chiles are tasty, but can they be good for you?

Ed Curry knows a thing or two about growing consistently mild peppers. He also believes in his peppers’ health benefits, which he thinks should be shared with as many people as possible.

Curry, who hosted an on-site portion of the pepper conference at his family’s chile farm in Pearce, has been working with chiles for a long time. His dad moved from Oklahoma to Arizona in 1952 and started with cotton and some chile peppers on the side. But the chiles were always variable, kind of a mess, Curry says.

When Curry was 8, the family visited Hatch, New Mexico, to look for better seeds. He remembers flying over the dark green fields, seeing little red chiles pushing through, circling over the crop that would eventually inspire their family’s whole business.

Curry Farms started developing chiles that gradually became easier to mechanically harvest, tasted milder and looked more uniform, a process that could be characterized as a friendly rivalry between Curry and Villalon, according to Benjamin Etcheverry, an agricultural operations supervisor with a food ingredient supply company that works with Curry Farms.

Though Curry and Villalon ultimately became known for different chile varieties, Curry respects Villalon and considers him a friend, along with longtime collaborator Phil Villa, who died in 2013. Etcheverry says Villa and Villalon were master breeders, and Curry absorbed their knowledge. All were keen to make the best peppers they could, and as a result, the exact origin of their inventions remains just a little bit murky.

Villa is listed as an inventor on patents for both Curry’s mild Anaheim-type variety and a type of no-heat jalapeño that references Villalon’s original paper from the 1980s. Curry says they didn’t use Villalon’s genetics, though Villalon “kind of thinks we did.”

In any case, “it’s very much an ‘iron sharpens iron’ type of scenario,” Etcheverry said. The constant back-and-forth, the debate about genetics and disease resistance and everything else, have helped drive the creation of several mild, easy-to-harvest, tasty peppers.

Now Curry has his eyes on a new frontier: making peppers as nutritionally valuable as possible.

Curry started the 2022 pepper conference with a prayer, seeking divine inspiration for scientists. He’s looking toward the future, and he believes that new chile varieties, particularly peppers with improved levels of certain compounds, could promote healthy aging.

Curry claims his peppers may one day stop macular degeneration (an age-related problem with the retina that can lead to vision loss) and slow Alzheimer’s disease. He’s not the only one preaching the power of pepper: Others in the industry talked at the conference about the potential of marketing peppers to consumers who are interested in health and wellness.

Bhimu Patil was one such speaker, but he doesn’t think peppers are a silver bullet. In a keynote speech at the conference, Patil, the director of the Vegetable and Fruit Improvement Center and a professor in the Department of Horticultural Sciences at Texas A&M, described some of the chemical compounds in peppers and the science of why they might be nutritious.

Some of the pepper varieties under development at places like Curry Farms contain high levels of lutein and zeaxanthin, types of carotenoids, the pigments that give peppers (as well as pumpkins, carrots and other foods) their color. Those chemical compounds are also found in the human eye, and they can help prevent damage from blue light.

But Patil acknowledged there is more work to be done before making any claims about these newer, compound-rich breeds of peppers. He said scientists need more studies to see how what levels of carotenoid compounds peppers can provide, and how many peppers people need to eat to prevent certain diseases.

Even with more evidence, Etcheverry doesn’t think touting the health benefits of peppers is all that attractive to consumers yet. Most pepper-eaters, he says, already know what they like, the flavors and quantities they need for their recipes.

That hasn’t stopped experts like Randall Hauptmann, Gopinathan Kizhikkilok and Curry, who all gleefully tout the promise of reaching health-minded consumers. Their optimism about next-generation peppers is palpable.

Curry is also an organic grower and is keen on promoting the health benefits of his crops. In a talk on consumer opportunities at the conference, Hauptmann and Gopinathan shared their excitement about packaging peppers for Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s.

But not all chile growers are interested in selling to that market. For others, it’s a little closer to home.

Traditional recipes for a new generation

Reyna and Feliciano Lara pride themselves on running a family business, and they have the tales to back it up, like how Feliciano met his wife when he saw her across the street in their small town. She ran home in the opposite direction, knowing that his family included some notorious womanizers. That didn’t stop him from pursuing her.

As they started the chile business, Feliciano would travel often between south Texas and Zacatecas ― two weeks here, two weeks there. He would drive and the family would take an all-night bus to go back to the farm and visit him.

Feliciano loves the land like people who play the piano by ear, Reyna says. He’s listened to it his whole life, and that’s how he knows it.

But to survive as a small business, the family has had to make improvements. After Feliciano first worked in California, he came back to the farm and showed his family how to put plastic over the field to cover parts of crops being watered by drip irrigation.

As they moved to selling dehydrated peppers, which they say is a harder task, they’ve learned through trial and error what techniques work and what they need to do to scale up. For instance, after selling wholesale, they started bagging their product in individual bags. That’s when the business started taking off.

What's the hottest pepper in the world?: These peppers rank as the spiciest you can eat.

For Reyna, it’s been a fight to get their product into stores. Managers put her down and said that the company wouldn’t make it. Many didn’t think dehydrated peppers could be profitable. Being a woman, Reyna noted, added to the struggle.

Over the past three years, she’s made it her mission to prove them wrong. Their company now sells products in stores all along the Texas border, with hopes of expanding to other states soon. The key, she says, is that they’re selling mostly to people who already have a sense of how to use their product, people who grew up seeing older family members cooking with dehydrated peppers, but had never given it a shot themselves.

The pandemic helped, as more people tried to cook at home and experiment with traditional varieties of peppers, varieties that brought back a familiar scent, a familiar memory.

They’ve received letters from customers whose families are also from Zacatecas, letters asking if they know certain people or congratulating them on the business.

“That was the most incredible part,” she said.

Some family businesses have also prided themselves on milder varieties, and it isn’t necessarily a straightforward cultural divide along the Scoville scale.

Jeanie Neubauer, one of the owners of Santa Cruz Chili & Spice Company in Tumacacori, south of Tucson, says most of her customers are Hispanic women, though she also gets some customers from other cultures. But her brand ― which she takes great pride in, as part of an almost 80-year tradition in her family ― is built on a consistently mild chile product.

The chile was a little hotter than usual this year, she said, and one person actually wrote in to complain.

But Neubauer thinks some people are getting used to chile that’s a little hotter, perhaps because more people are traveling and experiencing new flavors. Something about the American taste is changing.

Antonio Bacelar da Silva, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona who studies, among other things, the relationship between culture and food, says plenty of historical examples illustrate how people’s eating habits can be tied to the cultural, socioeconomic and political landscape. From eating meat in Argentina under Juan Perón to the Brazilian love of bread, “a lot of times, it becomes political,” Silva said.

Chile, as a commodity, is not just a food but a manifestation of collective taste, he said, a taste that is culturally constructed and informed by cultural pride. Chile, he added, is an important part of Mexican culture (and many other cultures around the world), but not everyone who profits from the crop is committed to respecting and supporting the food’s cultures of origin.

There’s a fine line between cultural exchange and cultural appropriation, and whether a certain variety of a crop falls on one side or the other is subjective.

Nearly all the chile experts at the conference ― from Reyna and Feliciano Lara to Curry, Villalon and Patil ― expressed appreciation for the cultures where chile originated. And in those places, spicy peppers remain significant.

But Santa Cruz Chili Co. has no plans to diversify their crop from their milder variety, at least not right now, Neubauer said. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel.

The test across the industry will be to see whether changing tastes translate into customers asking for more diversity in pepper offerings.

This is a consumer-centric country, she said, and food products will shift to match whatever its people desire. And whatever they want to pay for.

Melina Walling is a general assignment reporter based in Phoenix. She is drawn to stories about interesting people, scientific discoveries, unusual creatures and the hopeful, surprising and unexpected moments of the human experience. You can contact her via email at mwalling@gannett.com or on Twitter @MelinaWalling.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Why Southwest chile growers want to build a better pepper