The first women-only airplane race included Amelia Earhart. It made a stop in Fort Worth

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

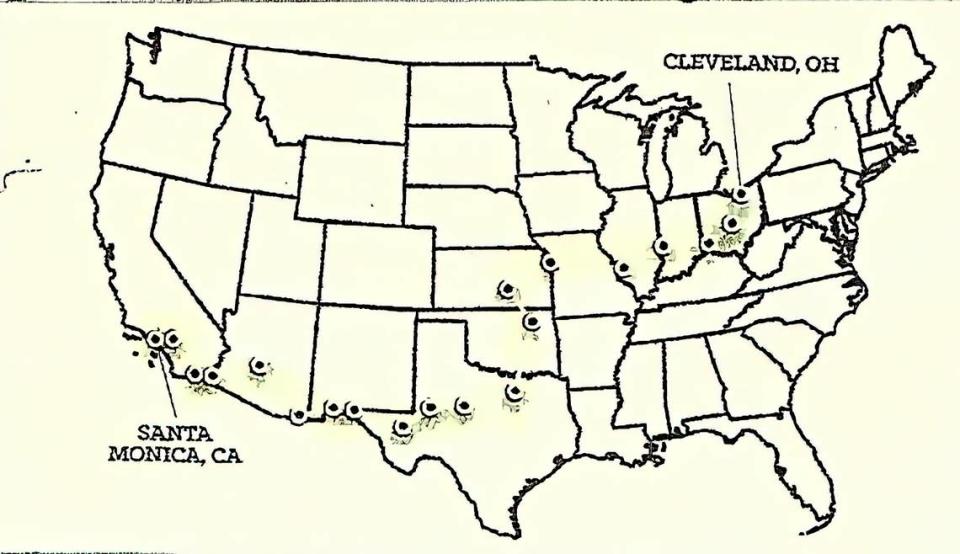

The first women-only air race was held in 1929. Men had been doing such things for years, but female pilots were still a rarity. The National Women’s Air Derby went from Santa Monica, California, to Cleveland, Ohio, covering the 2,800 miles in nine days.

Will Rogers dubbed it the “Powder Puff Derby,” and the name stuck, reinforcing the popular opinion that female fliers had no idea how their planes worked or how far they could fly on a tank of gas. A grueling, highly competitive event like this would go a long way toward dispelling those sexist misconceptions.

Twenty fliers entered the race, one-third of all the licensed women pilots in the country. They styled themselves “aviatrixes” and were determined to prove they were every bit as good as the men. Fort Worth celebrated when the route was announced because it came through the city and would bring the kind of national attention that appealed to the likes of Fort Worth Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter. “The ladies of the air” would arrive in Fort Worth on Aug. 22, 1929.

The route called for them to hopscotch across the southwest from California through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma. Then on to Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana before ending up in Ohio. They were supposed to fly only during the day because they would be navigating by landmarks on the ground, wherever possible following what fliers called the “iron compass” (railroad tracks).

The rules required them to check in at a series of “control stops,” spending the night there before resuming the next morning. The first to arrive got to take off first the next morning, followed by her competitors at intervals determined by how long after the first flier they had arrived. The cumulative record of who arrived in what order would determine the ultimate winner.

All the planes were open cockpit. Each flier was equipped with a map, food and water, and a parachute. The parachute was mostly for show because most crashes were on take-off or landing, and even if her plane came down in mid-flight and she parachuted to safety, her chances of surviving in the empty expanse of the Southwest were slim to none.

The most famous female fliers of the day took up the challenge, including Americans Marvel Crosson, Ruth Elder, Gladys O’Donnell, Louise McPhetridge Thaden and Amelia Earhart. Thea Rasch came from Germany and Mrs. Keith Miller from Australia. Prize money for the race was $24,000.

The race began on Sunday, Aug. 18, with the ladies taking off at one-minute intervals, starting with Marvel Crosson at 2 p.m. Their route took them across the southwestern desert with only occasional signs of civilization. Marvel Crosson went down in southern Arizona on Monday, her death the only casualty of the race. Four others were forced to drop out along the way either because of mechanical problems or illness.

Fifteen of the original 20 reached Fort Worth on Thursday, Aug. 22, landing at the municipal airport (Meacham Field). Louise Thaden arrived first at 5:34 pm, diving straight down to the field before leveling off at the last moment to come in for a landing. She was followed by Amelia Earhart doing the same thing. This cut seconds off their time, which could be important in calculating the winner. The last flier landed at 6:20 that evening. There were no other planes in sight, but the remaining four were expected sometime before dark. The schedule had them flying out for Tulsa, Oklahoma, early the next morning.

Welcoming them to Fort Worth was a crowd numbering in the thousands. The exhausted women had sun-burned faces and wind-blown hair and were dressed in a variety of knickers, coveralls, and jodhpurs. Their plans for the evening were to give instructions to their mechanics, then get to their hotel rooms for a bath and rest. Their Fort Worth hosts had other ideas. A banquet was scheduled in their honor that night, and they were expected to attend. Only Opal Kuntz refused, hanging a sign on her door that said, “Please go away and let me sleep.”

The Star-Telegram assigned Bess Stephenson to interview the ladies and write something from the female perspective. They shared their secret doubts about “the real value of airplane racing” to aviation or to the women’s cause. Some admitted that women had a long way to go to ever be accepted by their male counterparts. Still, they ridiculed the quaint racing rules placed on them by men, like only flying during daylight hours.

Edith Foltz did not reach Fort Worth until Friday morning, 14 hours behind the rest but determined to stay in the race. Departure Friday morning was 9 a.m., starting with Louise Thaden because she had landed first the previous day. Edith Foltz, fortified by plenty of coffee, was back in the air a scant three hours after landing. Margaret Perry who had also come in during the wee hours Friday was too sick to continue. Doctors diagnosed her with typhoid fever and ordered her to St. Joseph’s Infirmary.

The Thursday night reception and dinner were held at Amon Carter’s Shady Oak Farm with 10 fliers in attendance, including Amelia Earhart. They were treated to old-fashioned Cowtown hospitality. None of them had prepared remarks. Instead, they chatted amiably with their hosts as the evening’s festivities were reported live to a WBAP radio audience listening in.

On Aug. 26, 15 of the original 20 fliers landed at Cleveland. Louise Thaden, who had led all the way, came in first.

The success of this first-ever female air race produced some significant consequences, beginning with forming a national organization of women fliers. There was also some talk of creating a “feminine reserve corps” in anticipation of the “next war” using women fliers to ferry aircraft to bases, which would free up more men to do the fighting.

Fort Worth has long since forgotten the lady fliers who came through in 1929. But history didn’t. Frances Walton published a novel about the race in 1935, “Women in the Wind,” turned into a 1939 Warner Bros. film starring one of Hollywood’s leading ladies, Kay Francis, in the role of Ruth Elder. Released as a “B” movie, it failed to impress critics. Fort Worth was not mentioned in the film.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.