Five books from the 19th century that will help you understand modern America better

There’s a reason why one of the most important American novels of the twentieth century, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), begins with an epigraph by the writer Herman Melville and an allusion to the ghosts who haunted Edgar Allan Poe.

If you want to understand anything about the US in the 20th and 21st centuries, you need to know 19th-century American literature. The 19th century was when many, if not most, of the problems and ideologies that define American culture were codified, and literature of the period shows creative responses to this change.

For the first half of the 19th century, a lot of ink was spilt worrying whether the US would ever have a literature of its own. Many famous writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, urged Americans to leave English literature behind and take up specifically American themes, peoples and spaces.

At the same time, indigenous and enslaved Americans such as Harriet Jacobs, William Apess and Frederick Douglass used their pens and their rhetorical might to urge the US government to end race and ethnicity-based persecution and genocide.

After the American Civil War (1861-1865), writers rarely worried about whether the country had a literature and whether it was any good (it quite obviously was). They had innovated new genres (think of Emily Dickinson’s spare and searing verses) and turned their attention to issues of inequality embedded in American culture, as in Kate Chopin’s proto-feminist novella The Awakening and Charles Chesnutt’s exposure of racism and white supremacy in the post-Reconstruction South.

The following five works embody both the beauty of 19th-century American literature as well as its ability to change hearts and minds.

1. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs (1861)

Jacobs’ slave autobiography may not be the earliest written or the most famous, but it’s a devastatingly effective piece of storytelling that reads like a novel. Jacobs’ story of surviving slavery is so remarkable a narrative that sheds a rare light on the female experience of slavery.

Written under a pseudonym (Linda Brent), for a long time scholars assumed it must be fiction written by a white abolitionist. It wasn’t until African-American and feminist scholars unearthed the true identity in 1987 of Harriet Jacobs that the truth of her life story was accepted. Her narrative has since become a classic text of resistance, and it’s an essential read for understanding how white supremacy continues to function in America today.

2. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman (1855; last new edition 1881)

Walt Whitman was a virtually unknown journalist and printer when the first edition of Leaves of Grass thundered upon the American literary world. The strange book listed no author and contained a casual engraving of Whitman with hand on hip and head cocked to the side. Most importantly, it included poems like the world had never seen before. Poems with long cascading lines and little rhyme or metre to be found. Whitman continually added to and edited Leaves of Grass over the course of his life, crafting his biography in poetry that we now recognise as revolutionary in both form and content. It made Whitman a touchstone for 20th-century poets like Allen Ginsberg and Adrienne Rich.

3. Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868-69)

If you’ve seen the most recent movie adaptation of Little Women (or any of the many previous adaptations), you’ll know that there’s something about Alcott’s novel (originally two novels, now published as one) that strikes a chord. Written in the shadow of the Civil War, Little Women draws upon Alcott’s own remarkable family life among famous Transcendentalist writers and thinkers in Concord, Massachusetts. It’s a skillfully crafted book about how the dreams of childhood do and, more often, do not come to fruition.

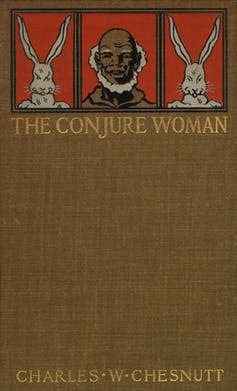

4. The Conjure Woman by Charles Chesnutt (1899)

In the late 19th centuries, a genre called “local color” dominated American literary magazines. These stories introduced areas of the increasingly expanding United States to those living in urban centres. African-American writer Charles Chesnutt turned this genre on its head in his series of “conjure” stories – tales of magic and cunning told by a formerly enslaved man named Julius to entertain a white northern businessman. Julius’ stories weave together African-American folklore and Southern Gothic ambience to expose white supremacy in the south before the Civil War. These stories indirectly comment on the racism that continued to haunt the post-Civil War US under a different guise.

5. Benito Cereno by Herman Melville (1855)

While these days Melville’s gargantuan 1851 novel Moby-Dick may be more famous (and you should definitely read that too, when you have a few months to spare), nothing packs a punch quite like the novella Benito Cereno. Based on the story of a real slave revolt on board a ship, the text is paced like a horror story and full of ambivalences and doubled meanings. It reveals the true horror of race-based chattel slavery and anticipates the eruption of violence that would tear apart the United States within a few short years.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jillian Spivey Caddell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.