5 times presidential primaries were upended in unexpected ways

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The final Republican primary debate of 2023 is set for Wednesday in Tuscaloosa, Ala.

The clash comes amid a race that has been unusually static.

Former President Trump has retained a massive lead in national polls, as well as in the key early states of Iowa and New Hampshire.

The drama up to now has mostly been around the battle for second place, with former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley on the brink of eclipsing Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, in part due to strong debate performances.

Trump has declined to participate in the three debates so far and he appears unlikely to change his tune for Wednesday.

The debate is hosted by NewsNation. The Hill and NewsNation are part of Nexstar Media Group.

Still, even though this year’s primary contest seems stable, there is a big historical caveat.

Previous nomination battles have shifted markedly in the final stretch before the first contests or after one startling result.

Here are five dramatic moments in the past 20 years, drawn from both major parties, where expectations were upended.

Democrats, 2004: Howard Dean surges then stumbles, clearing way for John Kerry

The 2004 Democratic race was defined by the debate over the war in Iraq, which had begun in March 2003.

Many leading Democrats had voted to authorize President George W. Bush to use force in Iraq. Electorally, some in the party worried that being seen as “soft on terror” could be deadly to the party’s chances of winning the White House back in 2004.

Yet enormous numbers of grassroots Democrats were viscerally — and presciently, as it turned out — opposed to the Iraq War.

Howard Dean, a previously low-profile former governor of Vermont, became the standard-bearer for the anti-war Democrats — a dynamic helped along because Dean was also more liberal on other issues such as health care.

When Dean fever was at its peak, it allowed him to blow past other significant figures such as then-Sens. John Kerry (D-Mass.) and John Edwards (D-N.C.). Just a few weeks out from Iowa, the caucuses were shaping up as a fierce battle between Dean and former House Minority Leader Dick Gephardt (D-Mo.).

In the final weeks, it all changed. The ferocity of the attacks Dean and Gephardt unleashed against each other turned off Iowans, sending them looking for alternatives.

Dean and Gephardt even ended up withdrawing negative ads heading into the final weekend of Iowa campaigning. But it was too late.

When Iowans went to caucus, Kerry won, narrowly holding off Edwards. Dean and Gephardt trailed in third and fourth respectively.

Dean tried to buck up disappointed supporters on the night with a loud, whooping speech. The “Dean Scream” became a political disaster all by itself.

Kerry, resurgent, went on to win the nomination relatively easily, though he would lose to Bush that November.

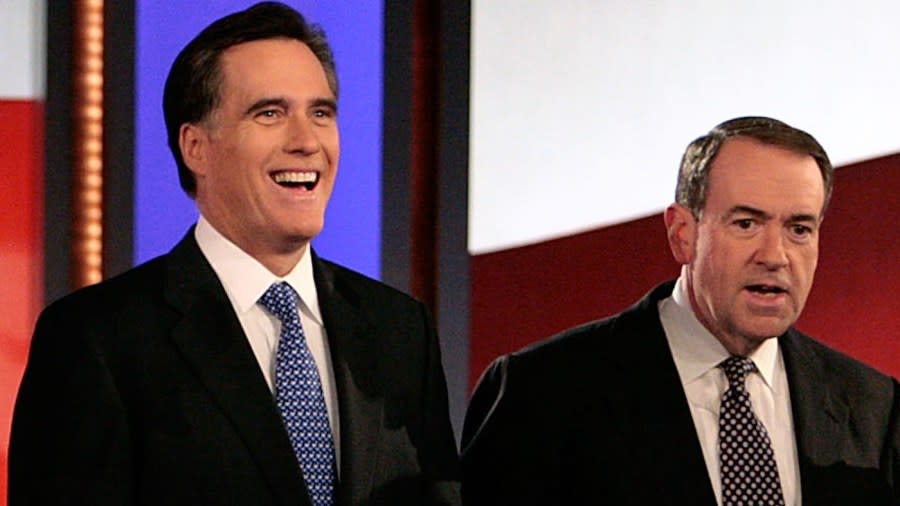

Republicans, 2008: Mike Huckabee sinks establishment favorite Mitt Romney

2008 is one of the campaigns often cited by aides to today’s non-Trump candidates as evidence that early polls mean nothing.

It’s a self-serving argument, but it’s not wrong.

At this time in the 2008 cycle, one ABC News/Washington Post poll put former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani 6 points clear of the rest of the field, followed by former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, actor Fred Thompson and then-Sen. John McCain (Ariz.).

The picture was complicated in 2008, however, because Giuliani opted for an unusual strategy of downplaying Iowa and to some extent New Hampshire in favor of concentrating on later big-state primaries, most notably Florida.

In Iowa, Romney led in polls for months. He was 23 points clear in the Hawkeye State in one October 2007 poll.

But Romney, a vastly wealthy businessman and a relative moderate on social issues, was loved more deeply by the GOP establishment than by the caucusgoers of Iowa.

The late-surging candidate in Iowa was Huckabee, who had recently ended an 11-year tenure in the governor’s mansion in Little Rock.

Back in 2008, his political persona was that of an avuncular Southern preacher. He said he was a conservative but “not mad at anybody.” He popped up on the Jay Leno-era “Tonight” Show playing bass guitar.

And, come caucus night, he walloped Romney in Iowa by almost 10 points.

Huckabee was never a good fit for New Hampshire. But his defeat of Romney destroyed any chance the latter had of taking a firm grip on the 2008 race.

It also opened the door for a comeback for McCain.

McCain won New Hampshire and rolled on to the nomination. Giuliani’s strategy proved disastrous. Romney came back four years later to finally win the nomination.

Meanwhile, the Huckabee political brand is now carried forward by Sarah Huckabee Sanders. The former White House press secretary under Trump won the Arkansas governorship in November 2022, marking the first time a daughter and father have served as governor of the same state.

Democrats, 2008: Barack Obama stuns ‘inevitable’ Hillary Clinton, who falls to third

Looking back at the Obama story now — two terms in the White House, the nation’s first Black president, resilient popularity — it’s easy to forget what a huge upset he pulled off in 2008.

Obama had come to national prominence with a speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2004, promising to transcend the divides of red and blue America and summarizing his own story as that of a “skinny kid with a funny name.”

At the time, he was an Illinois state senator seeking a U.S. Senate seat. He won that battle easily in November 2004. He went on to launch his presidential campaign before his Senate term had reached its halfway point.

Standing in his way was Clinton, then a senator representing New York. She had large swaths of the party establishment behind her. Beltway conventional wisdom held that the former first lady was all but inevitable.

In late December 2007, she led Obama nationally by roughly 20 points in the RealClearPolitics polling average.

But the situation was always more precarious for Clinton in Iowa. The state had, at the time, never elected a woman to either the Senate or the House, or as governor. Obama had the advantage of hailing from an adjoining state.

More importantly, Obama’s elevated rhetoric and charisma sparked intense devotion among the party’s grassroots.

Obama was obviously coming on strong in the final days. But the caucuses dawned with big questions still remaining about whether an overwhelmingly white and rural state would throw its backing to a Black first-term senator.

The answer was emphatic. Obama won by 8 points, while Clinton was nudged down to third place by John Edwards, making his second bid for the nomination.

Obama and Clinton went on to duke it out in an extraordinary and prolonged primary fight.

But, after Iowa, he never ceased to be the front-runner. Her campaign never fully recovered.

Republicans, 2012: Rick Santorum gives Romney another scare

The next cycle in 2012 offered another reminder that polls in December can be a bad predictor of who wins the nomination.

At this time 12 years ago, former Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) was leading the Republican race by double digits nationally.

The significance of the messy 2012 GOP primary has become far clearer in retrospect. It was the last time the GOP establishment was able to stave off deep discontent among the grassroots.

Activist conservatives looked for several candidates to scratch their itch early in the cycle, including Gingrich and businessman Herman Cain. Then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry raised hopes but never fulfilled them in a campaign best remembered for one especially disastrous debate performance.

It turned out to be former Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) who gave Romney the worst shock on his way to the nomination.

Santorum was, at root, a more ascetic version of 2008’s Huckabee. He had clear political limitations. He had previously won two Senate terms in Pennsylvania but had been thrashed by almost 20 points when he sought a third.

His ostentatious religiosity helped propel him to a shock victory in Iowa, though his campaign was deprived of a surge in momentum because the margin was so tight — roughly one-tenth of 1 percentage point — that the result only became official more than two weeks later.

Neither Santorum nor Gingrich could sustain their support for long enough to derail Romney. But the problems encountered by the establishment-friendly nominee were a sign of what was to come.

Democrats, 2020: Biden, buried in Iowa and New Hampshire, is resurrected by South Carolina

It’s not necessary to look back into the mists of time to see how primary fights can change on a dime. Just look at the current president.

President Biden was, to be fair, always strong in national polls of Democratic voters. Among the reasons: name recognition, durable loyalty from Black voters, in part because of his service as Obama’s vice president, and a belief among moderates that he offered the best chance of defeating then-President Trump.

But at one stage, it looked like none of those things would save Biden in the primaries.

His performances in the first states were dismal.

He came in fourth in the Iowa caucuses behind former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

The New Hampshire primary was even worse, as Biden dropped to fifth behind those three candidates as well as Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.).

But Biden had long put his faith in South Carolina, the first primary state with a significant Black population. The state’s voters repaid that faith, handing Biden a victory of almost 30 points.

The emphatic win was the catalyst for several other candidates, spooked by the possibility of the left-wing Sanders becoming the nominee, to drop out.

In a campaign constrained by COVID-19 restrictions, Sanders never really recaptured the magic of his 2016 bid that had run Hillary Clinton surprisingly close. Meanwhile, the center-left coalesced around Biden.

The rest is very recent history.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.