How to Fix Impeachment

The articles of impeachment haven’t yet been drafted against President Donald Trump, and seemingly everyone has a theory of what’s already gone wrong. Weeks of high-profile hearings and news reports on the president’s behavior have done little to change the minds of voters or lawmakers on either side, and few in Washington expect the exercise to end in anything other than a partisan standoff.

The finger of blame shifts from in-the-tank politicians to partisan media to a president who has made almost a sport of upending political norms. But maybe the blame lies more with impeachment itself—a last-ditch political safety measure written into the Constitution that has never, in 230 years, been successfully used to remove a president.

Is impeachment fixable? Is it even worth fixing? We rounded up nine experts on impeachment to tell us if this current process is working, and offer their ideas for how to fix the process in general, either through politics or changes to impeachment itself. Some told us the process is going just fine, and its many uncertainties are a feature, not a bug. Most agreed that even if the process overall holds up, it’s in need of a few ambitious fixes.

The proposals include a rule to prevent conflicts of interest among committee members, dusting off century-old tools to hold uncooperative witnesses in jail, an impeachment shot clock and letting the Department of Justice have a bigger role in presidential oversight in general. And one expert thinks that, with so much else that has failed, maybe process fixes can’t save us anymore—that the removal of a president should be left up to elections alone.

“Congress needs to pass legislation setting forth Department of Justice standards for investigating and prosecuting a president.”

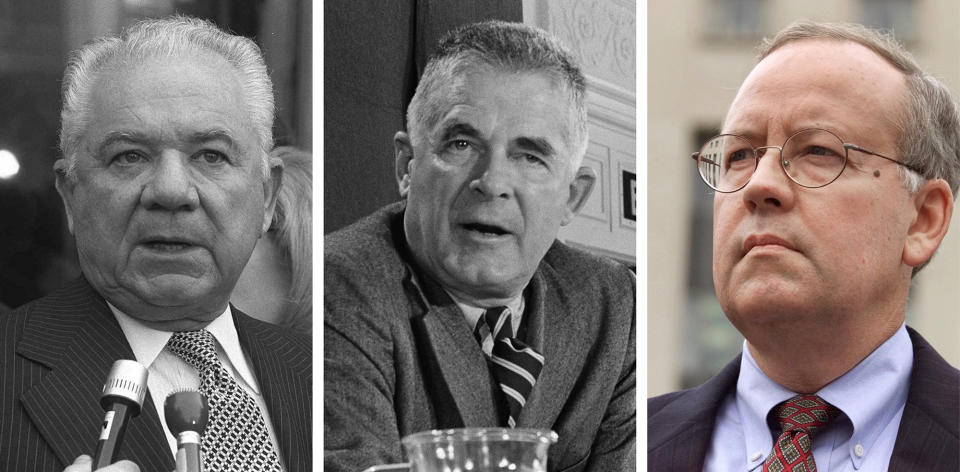

Kim Wehle is a CBS News legal analyst and a former assistant U.S. attorney and associate independent counsel for the Whitewater investigation.

The problem with the impeachment process is not with the Constitution itself—it’s with the apparent unwillingness of Republican members of Congress to vote their conscience and independently and objectively assess established facts. The burning question remains, which the testimony of constitutional experts in the House Judiciary Committee hearing underscored on Wednesday: If this conduct is not impeachable, what is? It’s difficult to pin down precisely what additional facts would hypothetically move Republicans to look askance at Trump’s conduct, let alone impeach. If the answer is—as it appears to be—that “there are none,” then the impeachment process is indeed broken.

Part of the problem is that, unlike in the impeachment processes for presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, there is a false counternarrative being peddled by Russian President Vladimir Putin that Ukraine interfered in the 2016 election and, therefore, that Trump’s quid pro quo request of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was justified. Unfortunately, certain media outlets and Republicans in Congress repeat this misinformation to the American public.

For prior impeachments, there was one set of facts produced and disseminated by reputable news outlets that self-regulated the quality of their reporting through norms and standards of journalism. The public received one narrative; the only question was what to do about it. Today, with social media, 24-hour cable news, the internet, media outlets that do not follow best practices, and the dissemination of lies from the White House with no political accountability, the facts themselves seem slippery to many Americans, making a legitimate impeachment vote virtually impossible.

But another problem is that impeachment is currently the only means of recourse available if a president commits a crime in office. Rather than attempt to amend the Constitution, Congress needs to pass legislation setting forth Department of Justice standards for investigating and prosecuting a president. That way, Congress is not the sole branch available to check abuses of power in the White House.

Today, internal DOJ guidance holds that a sitting president cannot be charged with crimes. In spite of the fact this is not codified in law—and that it is poorly reasoned, given the realities of modern politics—it constitutes a major impediment to the judicial branch’s ability to conduct oversight. With two branches functioning to oversee the executive, as the framers envisioned, crimes could be addressed through the high standards of the criminal justice system, while impeachment could remain a political lever of last resort.

In other words, the criminal justice system would deal with crimes that justify jail time under federal statutory law, and impeachment would deal with political wrongdoing that justifies removal from office. Today, the two issues are being blurred, as we saw in Wednesday's hearings, when Prof. Jonathan Turley argued that a crime must be proven in order to impeach, with the other three experts—Profs. Michael Gerhardt, Noah Feldman and Pamela Karlan—arguing that the question of impeachment is not about criminal liability under statutes passed decades after the Constitution was ratified.

We need an impeachment shot clock.

Philip C. Bobbitt is the Herbert Wechsler Professor of Federal Jurisprudence and director for the Center for National Security at Columbia Law School.

The problems we are experiencing in contemporary presidential impeachment aren’t merely a result of the impeachment process itself. They are symptomatic of much deeper problems with our democratic republic that arise from its loss of legitimacy in the eyes of many citizens, across the political spectrum. Impeachment proceedings won’t really be fixed until that much broader problem is resolved, and that will take decades of strife. But there may be modest amendments to the process that could help at least bolster its legitimacy in the meantime.

The Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton impeachments were built on the evidentiary foundation laid by independent counsels, special prosecutors authorized by statute that operated with a considerable degree of autonomy rather than strictly within the executive chain of command. Those independent counsels could go to court to challenge the president when he refused to cooperate with their investigations. We should not bring independent counsels back. I never approved, as a constitutional matter, of these arrangements, and I argued, for decades, with one of their principal architects, Lloyd Cutler, who, after the Clinton fiasco finally came around to my view.

But Congress’ refusal to renew the independent counsel statute, however, put the onus of investigation on the committees of the House that are not really adapted, or fully staffed, to conduct the kind of multi-year investigations undertaken by Archibald Cox, Leon Jaworski and Kenneth Starr. The special counsel substitute for an independent counsel, as we have seen in the Mueller Report, was also an inadequate compromise. The Department of Justice regulations under which the special counsel operated were far too confining to permit the wide-ranging investigations of previous eras.

Moreover, the House committees can be stonewalled by the executive (although few would have anticipated, I think, the total, run-out-the-clock tactics of the current administration). Basketball fans will recognize this as a form of “stall ball.”

What I propose is a kind of “shot clock” remedy that can augment the House investigatory process in light of presidential obstruction. I would favor a statute that provided for fast-track court hearings and expedited appeals as a way of curtailing the tactic of complete refusal to cooperate with requests for documents and testimony under oath before the House oversight committees. If the individuals subpoenaed still failed to comply after a court ordered them to do so, they could be held in contempt with all the political repercussions that would attend such a rebuke. At a minimum, it would be difficult to avoid the inference that something truly odious was being hidden.

Impeachment needs the legitimacy that the courts can provide, and it also needs timely and sufficient testimony. It simply cannot be that an administration can claim that the charges against it are without sufficient evidentiary bases and at the same time prevent the Congress from gaining access to the relevant evidence.

One cannot expect impeachment to work as designed if Congress does not work at all. But it still serves a useful function.

Frank O. Bowman III is a constitutional law professor and the author of High Crimes & Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump.

Impeachment is not broken. Congress is broken. Which is a much bigger problem. Nonetheless, impeachment may be able to serve a useful democratic function.

Midway through the process that will almost surely produce impeachment of Donald Trump in the House of Representatives and his acquittal in the Senate, there are several reasons one might view impeachment as “broken.” The reasons any given observer advances, like so much in our fractured political life, are likely to differ depending largely on that observer’s political perspective.

Those who view Trump as having demonstrated in many ways and on multiple occasions that he is unfit for office and a genuine danger to republican government may view impeachment as broken because it will not remove him. People of this view might reasonably ask whether a mechanism incapable of responding to precisely the sort of threat for which it was inserted into the Constitution is of any value.

Conversely, the loyal supporters of Mr. Trump are likely to complain that impeachment is broken because all the inquiries into his behavior are nothing more than vengeful efforts by Trump’s opponents to overturn the results of the 2016 election.

Both sets of complaints are reflections of a deeper malady—our politics is now so fractured that Congress has become increasingly incapable of performing any of its core functions. When the national legislature is unable, year after year, even to debate and pass a budget without histrionic confrontations that shut the government or threaten the nation’s credit, it is hardly surprising that it cannot effectively wield the extraordinary constitutional remedy of presidential impeachment.

More particularly, when the Framers wrote impeachment into the Constitution, they made several assumptions about Congress. First, as Alexander Hamilton candidly acknowledged in Federalist 65, they recognized that impeachment would inevitably summon partisan passions that could overwhelm considered judgment of the facts. But they also assumed some irreducible minimum of public virtue in at least a solid majority of elected public officials, and thus that when confronted by the danger of an obviously unfit and authoritarian president, partisan impulses would be subordinated to public duty. Second, they built the system of inter-branch checks and balances on the assumption that the members of each branch would naturally protect the institutional prerogatives of the branch to which they belonged even against threats to those prerogatives from another branch controlled by their own party. In short, they assumed that members of Congress would naturally resist any president, even one of their own party, if he continually encroached on congressional power.

Neither of these founding assumptions seem warranted in the present moment. The assumption that Congress would jealously guard its prerogatives against the president has been doubtful for decades, replaced by the dual tendencies to delegate even routine decision-making to the executive branch and to evade politically difficult choices like those involving war and peace. Congressional willingness to stand up for itself has declined still further under Trump and may have reached its historical nadir with the failure to override Trump’s emergency declaration that he had the right to take for his wall money Congress appropriated for other purposes.

And as for public virtue, at least if that means some minimal devotion to seeking truth and promoting the national interest over partisan advantage, I will leave to the reader the judgment of whether those qualities are on display, and if so by whom, during the current impeachment debates.

In short, one cannot expect impeachment to work as designed if Congress does not work at all. That said, even a hobbled impeachment process may yet serve a beneficial end. Impeachment remains a powerful tool for investigating presidential wrongdoing and exposing it for public judgment. In the present case, impeachment will almost surely not produce removal of Donald Trump, as in my view the Framers would certainly have expected it to do. But it will, at the least, shed light on his conduct and therefore allow the electorate to judge him in 2020. That is a genuinely good thing.

Congress should put uncooperative witnesses in jail—or at least remember that it can.

Mary Frances Berry is the Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of 12 books, including Why ERA Failed: Politics, Women's Rights, and the Amending Process of the Constitution.

Impeachment is not broken enough to require the almost impossible effort to amend the Constitution, which was deliberately made difficult to achieve. But given widespread frustration over the process, the House and Senate could make some changes before the next impeachment surfaces. These are simple changes in public relations and procedure which might increase confidence (even among participants) in the process, and reduce public polarization.

The House and Senate have powers that should be used next time if members believe the issue is serious enough for impeachment. Both chambers can hold witnesses in contempt and keep them under guard until they produce documents or agree to testify, even if witnesses subsequently assert Fifth Amendment immunity by refusing to discuss substance. Last used in 1935, Congress’ contempt power would be sure to trigger a backlash if used to hold Donald Trump or close associates in jail until they agreed to testify—but it’s a tool of last resort, and available in dire circumstances like these. A majority of the House or Senate must vote in favor. Obviously, if the House majority is prepared to impeach, it might also get the votes to approve contempt and detention.

Second, the House, and afterwards the Senate, should bend over backwards to appear apolitical. That means, for example, not using hearsay testimony to prove statements that the person being investigated made any particular statement. The investigation should not include witnesses to facts who are explaining what someone told them rather than what they actually heard or saw firsthand. Many Americans have seen trials at least on television and know that hearsay is usually inadmissible.

“Is a process that's undelineated, discreet and cautious broken? I don’t think so.”

Brenda Wineapple is author of The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation, recently published by Random House.

Impeachment is a court of last resort—not a criminal court but one convened to curb such offenses as the treason, bribery or high crimes and misdemeanors allegedly committed by a civil officer. In the United States, most impeached officers have been federal judges but, as we know by now, there have been only two American presidents who have actually been impeached, Andrew Johnson and William Jefferson Clinton. In both cases, the House voted to impeach and then the Senate, per the instructions of the Constitution, put the presidents on trial.

But the Constitution is a guideline, not a handbook. It does not define the terms “high crimes and misdemeanors,” which is what seems to stick in the throat of the process. For what are they? In Federalist 65, Alexander Hamilton clarified—sort of: a high crime is an abuse of executive authority, proceeding from “an abuse or violation of some public trust.” Impeachment is a “national inquest into the conduct of public men.” Murky: Are impeachments to proceed because of violations of law—or infractions against that thing called public trust? The answer is both, though it's absolutely true that the civil officer need not have broken a specific law—to have stolen a chicken, for instance, or have crossed the street against the lights. Rather, the framers of the Constitution were aware that anyone in a position of power must be held accountable for their actions in order to maintain a responsible and good government. To prevent an unprincipled demagogue from acting above the law, the framers thus incorporated impeachment into the Constitution, precisely to prevent corruption from within, keep elections free of foreign powers, and avert obstruction of justice or abuse of power.

That's where we are today, and what the legal scholars before the House Judiciary Committee told us on Wednesday. If a majority in the House of Representatives votes to impeach, the Senate, with the chief justice presiding, will conduct a trial to determine whether the president will be removed, which he will be, if two-thirds of the Senate concur. That’s the process. The Constitution does not specify how the trial is to be conducted, what constitutes evidence, who may object to that evidence, who might testify, or even if a president can or should. And remember: The impeachment trial takes place in the Senate, a legislative body, not a court of law.

It seems to me that the framers left the process purposefully vague, understanding that if the government endured, at different times, in the far future, different despots might arise to violate the public trust in unimagined ways. But is a process that's undelineated, discreet and cautious, to be considered broken? I don’t think so. If anything’s broken, it may very well be the faith with which men and women swear an oath to protect and defend the Constitution, and that oath includes the possibility of impeachment. If anything’s broken, it’s the concerted attempt to stop the process by calling it a hoax, a coup, a usurpation, a witch hunt.

The process is difficult to be sure, but it has held together during far more difficult times. Think of the impeachment of Andrew Johnson, which occurred after a brutal Civil War and the first-ever presidential assassination, when the country had just freed the 4 million people it had held in bondage and that Johnson wanted to keep in a state of perpetual subordination. During this fractious time, the impeachment process proceeded in orderly fashion despite the hostilities on both sides—hostilities, mind you, that had led to war. And yet the country endured. Andrew Johnson was impeached, not removed from office—not that is, until the next election, which took place mere months after his trial.

Maybe there’s a lesson there?

Impeachment is broken, but it can be fixed—first by taking a cue from another part of our justice system.

Corey Brettschneider teaches constitutional law and politics at Brown University. He is the author of The Oath and the Office: A Guide To the Constitution For Future Presidents.

Impeachment is a political process, not a legal one. Still, in order to ensure that the impeachment process is fair, the House and the Senate should borrow an obvious principle from criminal procedure: Jurors should not be implicated in matters they are asked to decide. Jurors in that position could vote self-servingly, instead of neutrally reviewing the evidence and determining guilt on the merits of the case; they would rightly be excluded from any jury.

The Senate and House should adopt a rule based on this principle. Such a rule would ban from any impeachment vote members involved in the Ukraine scandal who have clear conflicts of interest. Hyper-charged and partisan as the atmosphere is in Congress, impeachment is a solemn responsibility. Drafting a formal rule by a vote in each chamber or the adoption of a binding resolution pertaining to recusal in cases of conflict of interest, including any votes in the House and the trial in the Senate, would go a long way toward convincing the country that the ultimate result is fair. How can Congress ensure compliance with such a rule? On the weak end, one option is for the rule to require the chief justice of the Supreme Court ask each member whether they have such a conflict before the Senate trial and request that they recuse themselves if they do. More drastically, the rule might recommend a review of violations by the ethics committees of the House and Senate, enabling them to recommend sanctions to the full bodies of their respective chambers for members with conflicts who do not recuse themselves.

Such a rule would enhance the fairness of any impeachment trial, but it is especially necessary now given the fact that at least one member of the House, Devin Nunes (R-Calif.), and one member of the Senate, Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.), potentially face a real conflict of interest. Nunes had repeated contact with Rudoph Giuliani on matters central to the investigation, potentially implicating him in Giuliani back-channel pressure campaign on Ukraine. Johnson also held meetings with former Ukrainian officials and recently revealed that he spoke to President Trump about the withholding of the Ukraine aid.

Juries’ legitimacy relies on their impartiality. To include jurors who were involved in or knew about the alleged crime would inescapably taint the end result. The same is true here.

It’s our political system, not impeachment, that is broken. And only politics can fix it.

Allan J. Lichtman is a history professor and author of The Case for Impeachment.

Impeachment is not broken. The American political system is broken.

Impeachment is not the cancellation of an election. It stands equally in the Constitution with election by the Electoral College as a means of determining who is fit to serve as president. The framers did not vest impeachment in the judiciary, but in a political body, the U.S. House of Representatives, the “People’s House,” whose members were the only directly elected federal officials in the original Constitution. So, impeachment involves combined legal, political and moral judgments. It is a particularly apt remedy when a president’s abuse of power involves efforts to cheat in an upcoming election, which cannot therefore be a remedy for his transgressions.

The political system is broken. The Republican Party has abandoned its historic principles of limited government, fiscal restraint, respect for the judiciary, personal morality and responsibility, and states’ rights. Instead it has become a cult of personality behind President Trump, who has shattered all these ideals. That’s why the Republicans so far have maliciously attacked the impeachment process and blindly defended the president, no matter how powerful the evidence against him.

The Democratic Party has maintained its historic principles but lacks a spine. For many months, it delayed launching an impeachment investigation despite ample evidence of the president’s abuse of power. It acted only when forced to do so by the president’s own gratuitous actions: his shakedown of a foreign power to sacrifice our national security and help him cheat in the 2020 election. Now, Democrats are making the opposite mistake of rushing the impeachment process.

There is not enough yet on the record to move Republicans in the House or Senate. Perhaps no evidence, however compelling, will do so. But there is hope for the Democrats, who might only be able to fix a political problem with a political solution. They need to delve more deeply into former special counsel Robert Mueller’s findings on obstruction of justice and collusion with the Russians. Incriminating new information is coming out through Freedom of Information Act requests by private parties. Democrats should wait to see if they will soon obtain Trump’s financial records. They need to link impeachment tightly to Russia, to reach the independent voters that may well decide the political survival of Republican officeholders. Politics is what got us here—it will have to get us out of here, too.

“No amendment to the Constitution could eliminate partisanship and inefficiency.”

Alan Baron is former special impeachment counsel to the U.S. House of Representatives.

The impeachment process is not broken, and I see no compelling reason to amend the Constitution to “fix” it. First, some statistical information: There have been only 19 impeachments of federal officeholders in the nation’s history. The impeachment of a president is both momentous and, fortunately, a rare occurrence. We need to ask whether it is in the nation’s interest to take the extraordinary step of amending the Constitution to address a situation that arises so rarely.

The impeachment process has been criticized as overly partisan, inefficient and cumbersome. But we must recall that, at its core, impeachment is political. Impassioned participation by the members of the House and Senate inevitably makes the process both partisan and inefficient. No amendment to the Constitution could eliminate these two qualities.

Accountability reform might fix this process. A lot of accountability reform.

Julian Epstein was the chief counsel for the Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee during the impeachment of Bill Clinton.

Impeachment is broken because our politics are broken. Our culture wars have descended into Manichean conflict where neither party listens to the other side—what Arthur Brooks, former president of the American Enterprise Institute, calls the “culture of contempt.” The public square is dying and with it so is our ability to persuade the other side of nearly anything, impeachment included.

No president has ever obstructed Congress with laughable claims of blanket-privilege as this president is doing. But the Trump administration believes it can get away with it—and may get away with it—because in these dysfunctional politics the law and norms increasingly don’t matter.

In the meantime, there are reforms that can help fix the impeachment process and the means by which the legislative branch holds the executive accountable. It is completely unclear to me why the media has not asked every candidate for president where they stand on accountability reform, or why activist groups haven’t created a movement behind it. There are some obvious reforms clearly needed such as statutory guidelines on executive privilege claims which, consistent with case law, would have prevented this White House’s bogus assertion of absolute immunity from Congressional oversight. We also need updated statutory rules for Congressional access to agency documents like the Mueller report grand jury materials and OMB budget documents on withheld military aid to Ukraine—both of which the administration has no business blocking now. Most importantly, we need statutory shot clock that requires the next administration to respond to subpoenas within, say, 30-45 days—with expedited judicial review including to the U.S. Supreme Court for obstructive acts.

Every Democratic and Republican candidate for president should be asked for their plan fixing our civics and hold the next president accountable with clear statutory based rules. And it should be top of the agenda for the next Congress.