Flashback: 250 saleswomen barricaded doors of Detroit retail store in 1937 sit-down strike

Detroit’s unions took a militant turn this year, with striking workers from multiple industries marching in the streets and UAW President Shawn Fain wearing an “Eat the Rich” T-shirt. They were among thousands of workers who went on strike this year, from screenwriters in Los Angeles to casino workers across town. But 2023 doesn’t compare to 1937, when a stunning wave of sit-down strikes in the city followed the famous sit-down in Flint. The following report about the events 86 years ago are excerpts from “Working Detroit,” Steve Babson’s critically acclaimed history of the city’s labor movement that was published in 1984.

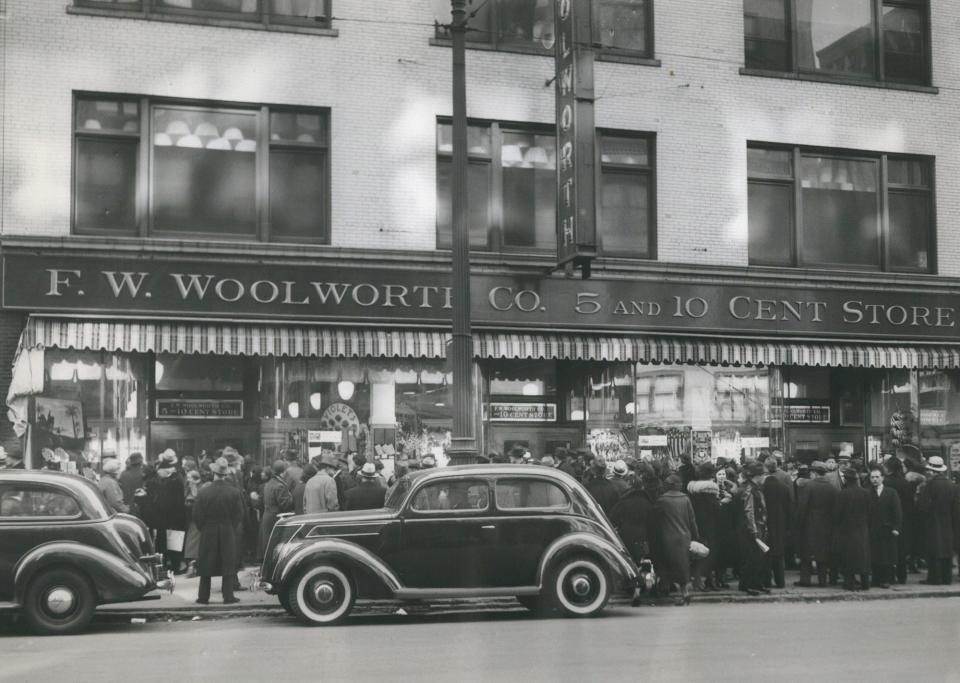

Among the hundreds of shoppers crowding into Woolworth’s downtown store on Saturday, Feb. 27, 1937, few would have guessed the young women and teenage girls behind the counter were about to seize their employer’s store.

Suddenly, without warning or fanfare, an organization from the AFL’s Waiters and Waitresses Union strode to the center of the main floor, blew a whistle, and shouted “Strike!”

As whistle-blowing activists spread the pre-arranged signal through the building, 250 saleswomen stepped back from their customers and folded their arms: Downtown’s first sit-down had begun.

The eight-day occupation of Woolworth’s flagship store followed many of the patterns established in Detroit’s factory occupations — and added many new wrinkles peculiar to its own setting. Like their industrial counterparts, the Woolworth workers evicted management and barricaded the doors when the company refused to bargain. But no one knew quite what to do with the 200 customers who decided to join the strike.

“Patrons of the store seemed to enjoy the experience,” reported the Detroit Times, “and only a few left when warned the doors were to be locked.” Eventually, the strikers had to ask these good-natured allies to leave.

The magnitude of the militancy

“If lawless men can seize an office, a factory, or a home and hold it unmolested for hours and days, they can seize it and hold it for months and years; and revolution is here …”

Detroit Saturday Night, March 20, 1937

“Revolution is here” — so it seemed to the worried editors of Detroit’s leading business weekly in March 1937.

Although no homes were “seized,” everything else seemed to be fair game in the winter and spring of that year.

The afternoon of Monday, March 8, was especially notable. At 1:30 p.m., a well-planned sit-down simultaneously swept all Chrysler factories in Detroit: Dodge Main, Plymouth Assembly, DeSoto, Dodge Forge, Dodge Truck, Amplex Engine, Chrysler Kercheval Avenue and Chrysler Highland Park. About 17,000 UAW supporters, joined by hundreds more in nearby plants of Hudson Motors, barricaded themselves inside Detroit’s major automobile factories.

In the weeks immediately preceding and following this stunning escalation, the sit-down wave spread through virtually every industry in the city.

Four hotels, including two of downtown’s largest, were occupied. So were at least 15 major auto plants — including Chrysler — and 25 smaller plants; a dozen industrial laundries; three department stores and over a dozen shoe and clothing stores; all the city’s major cigar plants; five trucking and garage companies; nine lumber yards; at least three printing plants; 10 meat-packing plants, bakeries and other food processors; warehouses, restaurants, coal yards, bottlers and over a dozen miscellaneous manufacturers.

In all, nearly 130 factories, offices and stores were occupied and held for a few hours or up to six weeks. According to newspaper estimates, 35,000 workers joined these sit-downs and over 100,000 others walked picket lines outside the plants.

Even non-employees sat down. On March 11, 35 relief recipients occupied the Fort Street welfare office and demanded the removal of an unpopular supervisor. They were evicted the next morning. Three days later, 30 members of the Michigan National Guard sat down on the steps of the of the Ionia Armory, demanding back strike pay for their strike duty in Flint. They were promptly paid.

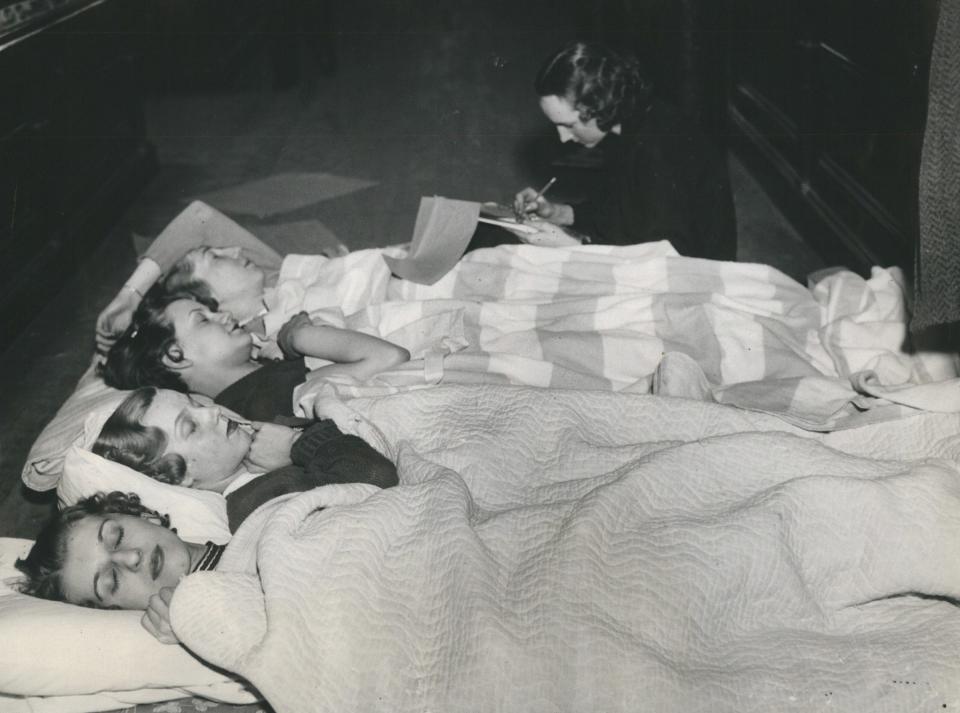

As the sit-down wave rolled across the city, thousands of non-strikers were drawn into the movement. Store owners in working-class neighborhoods donated food and other provisions. The Salesman’s Union canvassed furniture stores to secure mattresses for the sit-downers. Unionized pharmacists filled prescriptions for the sit-downers without charge and the Detroit Federation of Musicians sent a small orchestra to the Crowley Millner department store to play dance music for the sit-downers.

Striking the American way

To union supporters, these events heralded a hopeful new beginning for the city’s labor movement. To the Detroit Board of Commerce, they heralded something completely different.

“We have a right to feel upset,” the board editorialized in its weekly, The Detroiter, “when we feel the influence of acknowledged Communists …”

Some of the secondary strike leaders were, indeed, Communists, but the great majority of sit-downers were not revolutionaries seeking to “Sovietize” America. Most saw themselves as loyal Americans seeking to force the law of the land and win rights legally denied them by their employers.

They wanted collective bargaining to humanize the corporate system and a “New Deal” to spread its benefits more equitably. Most had no intention of running the plants without capitalist management.

Autoworkers marched in the streets with American flags; Woolworth strikers reportedly sang “America” when their boss refused to negotiate. Even so, in the hands of sit-downers, these patriotic symbols conveyed very different meanings from those traditionally expressed at American Legion picnics.

In practice, sit-downers and their supporters acted on principles of solidarity and group commitment that stood in sharp contrast with the ideology of individual upward mobility. Their goals were defined more often in terms of collective security and dignity.

“We weren’t for getting rich,” recalled Bill Mileski, a sit-downer at Dodge Main., “because you can never get rich working. We wanted seniority, so the guy didn’t have to be a kiss-ass to keep his job.”

The Woolworth women organize a Love Committee

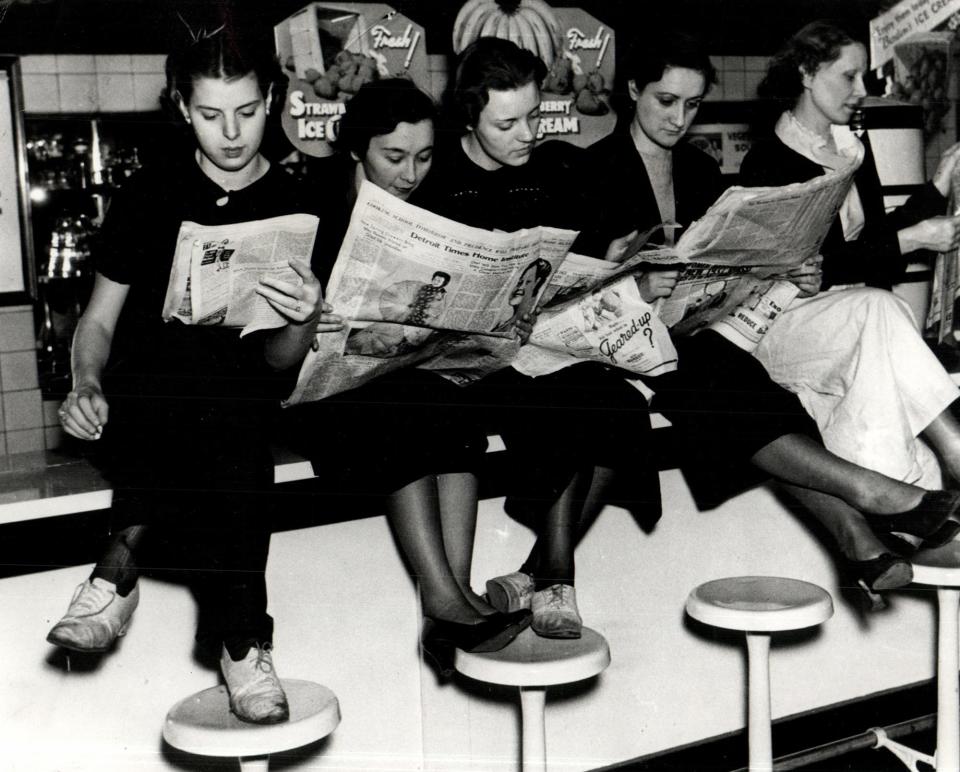

Like sit-downers in dozens of factories, the Woolworth occupiers established a galaxy of committees to sustain their struggle and build morale. For the mostly teenage girls cooped up for eight days in the darkened store, food and bedding committees were not enough. The romantically inclined youngsters on the Love Committee therefore established a booth where couples could spend five minutes during visiting hours.

The Entertainment Committee was especially active, arranging sing-alongs, concerts and speeches by special guests.

“I was really thrilled when I heard what you cute kids had done,” said Frances Comfort of the Detroit Federation of Teachers at one such appearance. “Some people say you’re lawbreakers, but I’m here, a schoolteacher, proud to be among you.”

Feature stories by Pathe News and Life magazine gave nationwide exposure to these novel aspects of white-collar militancy. But underlying the often superficial coverage were deeply felt grievances.

The young women and girls at Woolworth’s worked a 52-hour week, were paid 28 cents an hour and barely cleared $14 ($296 adjusted for inflation) after six days — about half of the wage of unskilled autoworkers.

After the Woolworth workers seized a second store, at Woodward and Grand Boulevard, they won union recognition and a 5 cents an hour raise. Their victory touched off a rapid series of sit-downs among underpaid hotel and restaurant workers.

Solidarity forever

The sit-downs welded workers of diverse skills, nationalities, races and religions into a powerfully movement. To an unprecedented degree, the sit-downs also merged the goals of women and men.

Thousands of women were not only joining the labor movement, but many were occupying their workplaces with the same determination and militancy as male trade unionists.

Housewives were also drawn into the fray, preparing meals in strike kitchens, canvassing local merchants for food, walking in picket lines or speaking out on behalf of their husbands and children.

“After we got together, we felt our strength,” said Bebe Catherine Gelles, a former autoworker whose husband and sister-in-law joined the Kelsey-Hayes sit-down. “We felt we were strong because we weren’t individuals any longer. We were part of an organization.”

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: In 1937, Detroit workers kicked out their bosses in sit-down strikes