Flashback: In 1973, 1 of Detroit’s most significant mayoral elections was playing out

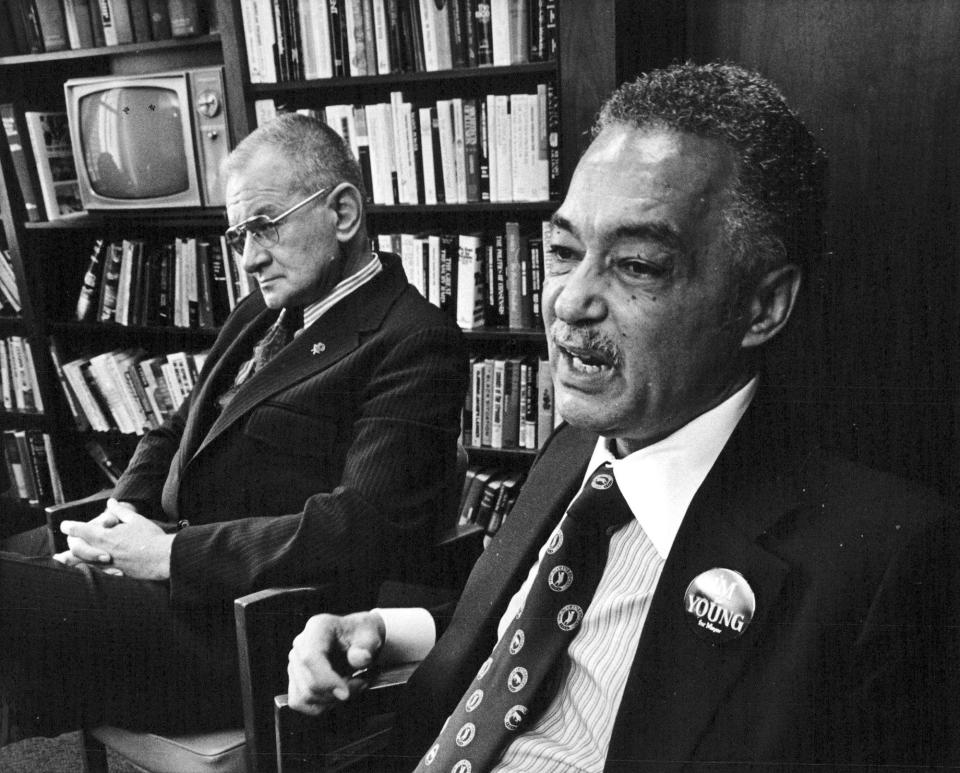

Fifty years ago this fall, one of Detroit’s most significant mayoral elections was playing out, with former Police Commissioner John Nichols and state Sen. Coleman Young running at a precarious time in the city’s history. Young won, of course, but no one knew the outcome when the candidates met for a debate at the Free Press about a month before the vote. A transcript of their encounter ran in the paper Oct. 7, 1973, and includes issues that remain relevent today. The following excerpts have been edited for length.

Q. What are the main differences you see between you?

NICHOLS: The senator’s experience, I think, has been in the legislative branch and my experience has been in the executive branch. My experience has been on the streets while his has been in the learned halls of lawmaking.

YOUNG: Well, I question that the commissioner has had any more experience in the streets than I have had. I was raised and born in the streets. I've been on the other end of a nightstick from him; it might give me a different perspective of the streets. I refuse to be described as a legislative expert only.

I have performed many executive functions including command functions in the armed forces and executive functions of business operations, and organizational and executive functions in the labor movement. I consider that I have a broad spectrum of experience and background, while the commissioner has a very narrow one — a monolithic, single one.

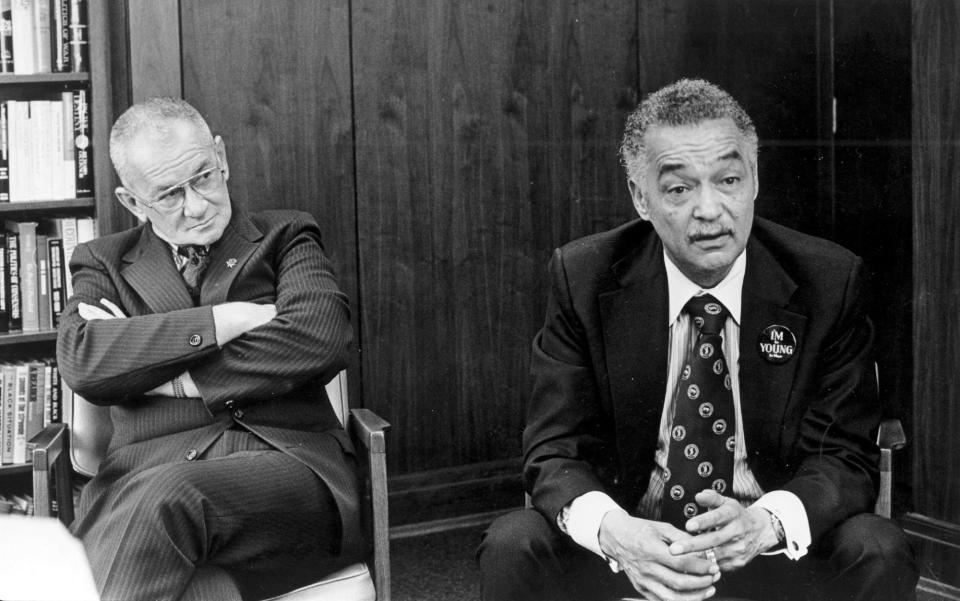

Q: Both of you, in this election campaign, have to reach for support outside your constituencies in the primary. Mr. Nichols, why should blacks vote for you, and Mr. Young, how do you appeal to whites?

NICHOLS: For the same reason I think that whites should vote for Senator Young.

Because I think that if the future of this city has to be predicated on the color of an individual's skin, we are in more damned trouble than we ever deserved to be in. I would hope that if there's one white man out there who's going to vote for me simply because I am white, that he would stay home on election day. I don't think that the criteria should be how much we can appeal to each other's ethnic group, but rather how much we can appeal to the broad base of citizens. I would hope that the senator shares this belief in that we should be selected for what we stand for and not for who we are or what our accidents of birth may have made us in terms of skin pigmentation.

YOUNG: I have no problem with that general approach.

I have said before that I'm running on a program. I espouse no position which is good for blacks which I don't consider to be good for whites and vice versa. I hope to be judged and I expect to be judged based on my programs. I'm not naive, I know there is polarization in this city. I'm seeking to close that polarization and to unite the differences between the races.

How Young's campaign started: Sen. Young had to go to the Michigan Supreme Court to run to be Detroit's mayor

Q. What should be the role of the police in this city?

YOUNG: Obviously, the role of police should be enforcement of the law with impartiality and professionalism. I believe that a police department that has its roots in a community, that has the respect of the community and has the cooperation of the community is the only guarantee that we can have a more stable community that has the potentiality of growth and vitality that Detroit needs. Now that is the role of the police department as I see it. This is the type of police department that I will build as mayor of the city of Detroit.

NICHOLS: I would have to differ basically, as a former law enforcement officer, on the philosophy that the first mission of the police department is enforcement of law. I see, as most police administrators see, that the first mission of the police department is the prevention of crime. And, be that by preventative patrol or by crime prevention programs, that is the way the department is currently oriented and that is the way I would continue its orientation.

Certainly I cannot deny the fact that so long as one individual must stand in the forefront of society's needs and desires as opposed to an individual's lawless desire — that he will ever be beloved by everybody in the community. I think that the very fact that the police officer's role in society often places him in this position, precludes his capability of always being the Number One man in the hearts and minds of everybody.

And, philosophically speaking, we differ on the actual practical delivery of police services.

Q. Do you believe Detroit is correct to require civil servants to live in the city?

NICHOLS: That's almost an academic question isn't it, gentlemen, since I almost got run out of town for enforcing the residency ordinance among the police department. Yes, I believe it's true for primarily several reasons. First there's an economic reason — we pay our city employes a fairly respectable rate of pay. I think it's not unusual we ask they participate by a return of that in terms of taxes and in terms of city living.

I think it's particularly important that the city employees be in a position where they can vote for the individuals who are going to lead them, to guide them and direct their policies for the next three or four or five years. And I think that in addition to that there is probably a certain amount of viability in the theory that an individual will participate a little better in that in which he has a stake. So I certainly would support residency and that would include the teachers, too.

YOUNG: My answer is yes, I'm in favor of residency.

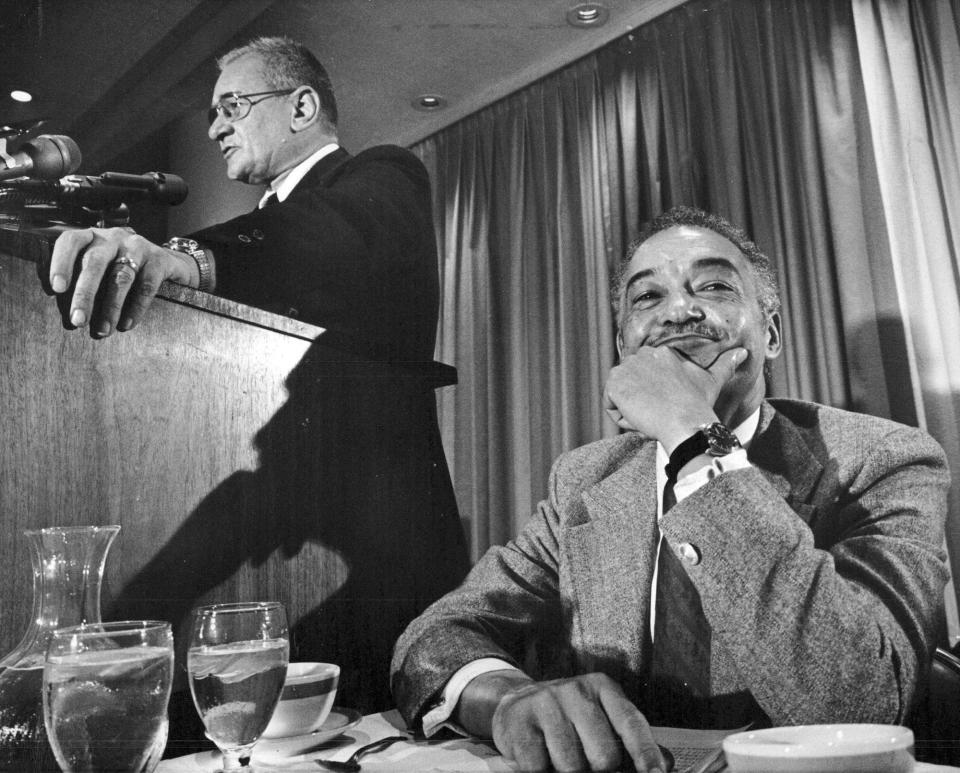

Q. What is your vision of the Detroit you'd want to see exist four or eight years after you've been in office?

YOUNG: I'd like to see a Detroit that is on the way up. A Detroit that is growing, that is vibrant, that is united. A Detroit from which the fear of crime has been removed. A Detroit where job opportunities exist for our young people and where quality education is available in our schools.

A Detroit that has lifted the drug traffic. A great dynamic and growing Detroit, and I believe that after four years of my administration, with the cooperation of the people of this city, we can and shall have that type of Detroit.

NICHOLS: I don't think there can be much difference in the basic philosophies of what the senator and I would envision. I think that a city living in harmony, a city of growth, a city in which the spirit of the city of champions can be exemplified, a city with job opportunities, a city with no discrimination, a city where the crime syndrome has been removed, a city who thinks highly of itself and who holds its head up and who projects the image of a great city and a vibrant city.

And more important, a city in which people can live together and coexist much in the same spirit that exists on a limited basis in our ethnic festivals on the riverfront.

It would seem that the spirit is there if somebody can just activate it and bring it forward and keep moving from month to month and year to year rather than on just one or two weekends.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit mayoral debate in 1973 covered issues that still resonate